The decision to have a child is deeply personal, and in the United States, parents are having fewer children. This story is the first in a series about falling birthrates. The second shows how immigrants are powering a population boom in rural Iowa. The third looks at the tumbling global birthrate and hard societal choices ahead.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

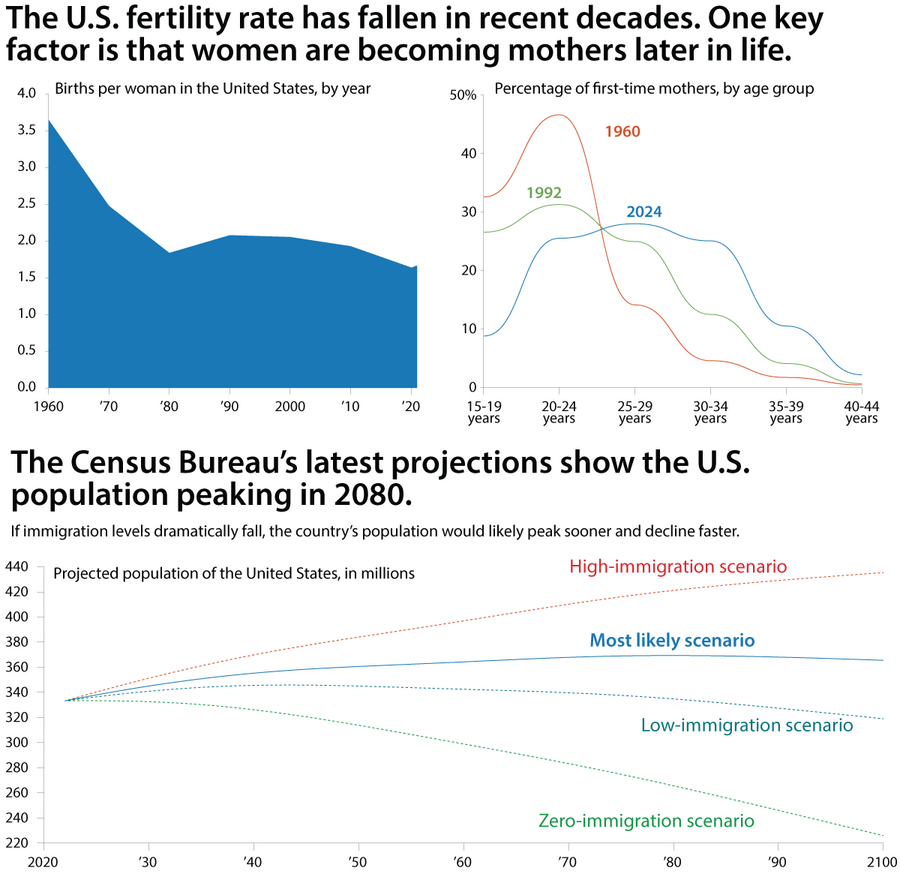

Everyone loves a mystery, and today we have one for you. Why are birthrates falling across so much of the world? We once feared cataclysmic overpopulation. Now it seems the global population might shrink before the end of the century.

No one has definitive answers. But in exploring the issue in a series of stories this week, Simon Montlake is asking the important questions about how it might reshape our world.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 10 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Texas immigration law: A federal appeals court refuses to lift an order that blocks Texas from arresting and deporting migrants suspected of illegally crossing the U.S. southern border.

• Moscow attack suspects in custody: Eight suspects are now in pre-trial detention since gunmen sprayed concertgoers with bullets in the deadliest attack in Russia in two decades.

• France, Brazil join to protect Amazon: The presidents of Brazil and France announce a plan to invest $1.1 billion to protect the Amazon, including parts of the rainforest in neighboring French Guiana.

• Landmark marriage equality bill: Lawmakers in Thailand’s lower house of parliament overwhelmingly approved a marriage equality bill that would make the country the first in Southeast Asia to legalize equal rights for marriage partners of any gender.

( 7 min. read )

Canadians have trusted that their immigration system would let people into the country in a manner that would benefit all. But amid a record influx, the balance seems to be out of whack and trust is eroding.

( 5 min. read )

The collapse of a major bridge in Baltimore after a cargo ship struck it on Tuesday raises questions of safety. Such collisions are rare, but improvements can be made, say experts.

( 4 min. read )

In India, sacred groves have become bastions of biodiversity. But how effective is spiritual belief as a tool for conservation?

( 2 min. read )

In Taiwan, making wheat vermicelli mostly by hand is a dying tradition. Here’s one family that is still following the centuries-old process passed down through generations.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

Many people may know Gibraltar only by its wedge-shaped outcropping at the opening of the Mediterranean Sea or by the Beatles song about the marriage of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Yet it may now be poised to show how perceptions of government malfeasance can lead to renewed public integrity.

An upcoming trial offers “a familiar scenario to those who study corruption: a scandal leading to reform,” noted Robert Barrington, a University of Sussex professor, in a recent post on The Global Anticorruption Blog.

The heightened concern about corruption in Gibraltar, a territory under British authority at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, dates back four years. In 2020, its top law enforcement officer, Ian McGrail, abruptly retired halfway through his term as police commissioner. Gibraltar has been on and off international watchlists in connection with illicit financial activity such as gambling, money laundering, and funding for terrorism. Mr. McGrail said he was forced to resign just as he was poised to expose fraud by senior officials.

The government subsequently launched an inquiry into Mr. McGrail’s departure. It also charged him with various crimes, including sexual misconduct and a breach of data relating to the inquest. Those allegations have since been dismissed, and the inquiry – set to start April 8 – has now effectively become a trial of government corruption.

There’s one final twist. In an apparent attempt to expand its oversight over the legal proceedings, the government rushed through a new law under emergency rules this week granting itself the power to either shut down official inquiries or conceal hearings from the public.

That may have been a salutary miscalculation. The new law has sharpened scrutiny from opposition leaders and global corruption watchdogs ahead of the trial. It may also improve the balance of power in a system in which the executive and legislative branches of government are deeply intertwined. The law is modeled after a 2005 reform in Britain that scholars say has strengthened judicial independence and has enabled more effective public scrutiny of government.

Responding to concerns by Transparency International that the new law may “fetter the independence of the inquiry, obstruct its timely progress or unduly influence witnesses,” the government has felt compelled to offer repeated assurances in recent days that it has no intention to interfere in or halt the inquiry.

A 2019 University of Leiden study of corruption in the Mediterranean island nation of Malta offered a granular view of how flows of illicit international finance exploit the unique vulnerabilities of small states or governates. Smaller electorates, found by the study, are prone to cozy patron-client relationships that result in cultures of impunity and undercut “the ability and willingness of citizens to hold politicians accountable.”

Yet it also found that in smaller settings, “citizens have greater opportunities to scrutinize the extent to which politicians actually deliver on their promises,” which can result in deeper public trust in democratic institutions and procedures.

A year ago, Gibraltar’s government passed legislation establishing a new anti-corruption authority. It has yet to follow through. The McGrail inquiry has now raised public expectations. “If the picture that emerges is of a corrupt government that is complicit with organised crime,” Professor Barrington noted, “there is an upside.” More accountability and transparency in Gibraltar would give global financial integrity another foothold.

*Editor's note: An earlier version of this editorial contained a misspelling of Mr. McGrail's name.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

If we’re looking for a better understanding of ourselves and a stronger foundation for relationships, getting to know God – our divine Parent – is a reliable place to start.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for our second story about the global baby bust. With the U.S. working-age population set to start shrinking, rural areas like Sioux City, Iowa, are finding that migration can be a force multiplier.