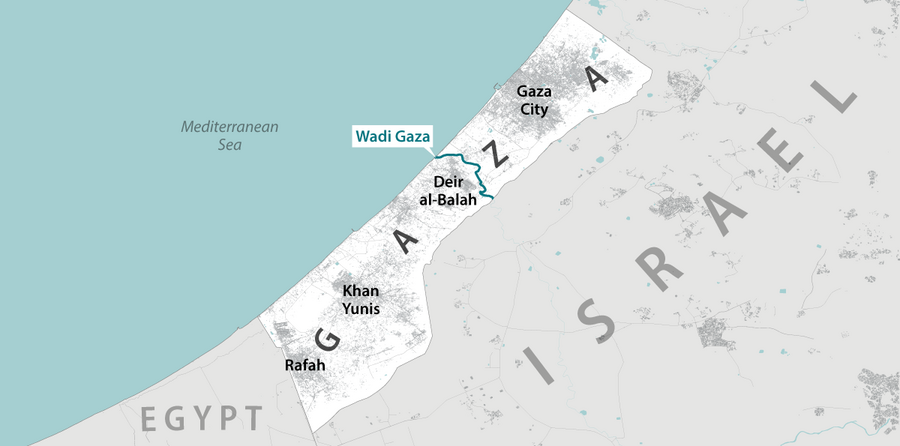

Caught in the middle of the Hamas-Israel war, and with opposing orders from the combatants, 1.1 million civilians in northern Gaza must decide whether safety means leaving their homes. Our reporter had to make the agonizing choice.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Scott Peterson

Scott Peterson

As the scale and significance of the surprise Hamas raid against Israel become clearer, questions are being raised about Iran’s role. Might the Islamic Republic’s long-standing antipathy toward Israel lead to a broader and even more destructive regional fight?

During a recent visit to Lebanon, I was surprised by the determination of veteran Hezbollah fighters to take on Israel directly. The militant movement is backed by Iran and is far, far more militarily capable than Hamas. The fighters described their eagerness to take part in an inevitable next and “final battle” against Israel – targeting airports, barracks, and bases, and seizing large parts of territory.

As I explored further, however, it became clear that Hezbollah’s leadership had recently taken multiple steps to de-escalate – to ensure that high-stakes events with Israel never spiraled into war. Likewise, analysts noted that the decision for a Hezbollah-Israel war would be made by Iran.

American and Israeli officials have stated they see no evidence of a direct Iranian role in the Hamas assault. Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei this week denied any role. Aware of the risks of a broader conflagration, leaders on all sides appear to have little appetite for one.

Iran is already grappling with widespread internal unrest and a dismal economy crushed by U.S.-led sanctions. It has eased back its nuclear program – in an apparent unwritten agreement with Washington – and dabbled in reconciliation with Arab neighbors.

In that context, it is noteworthy that Hezbollah did not launch its own assault from the north. In the first few hours of Hamas’ offensive, Israel’s intelligence and military were clearly knocked off balance – a moment Hezbollah could have taken advantage of.

It reminds me of an incident 15 years ago, when an Israeli offensive in Gaza killed 1,400 Palestinians. Iranian recruits hungry for revenge showed up at an airport in Tehran, ready for battle. In the end, someone from the office of archconservative President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had to go to the airport. His message: Go home.