Mexico was never a “migration nation” like the U.S. But American policy written during the pandemic has caused a bottleneck at the border – and forced Mexicans to rethink their obligations to migrants.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

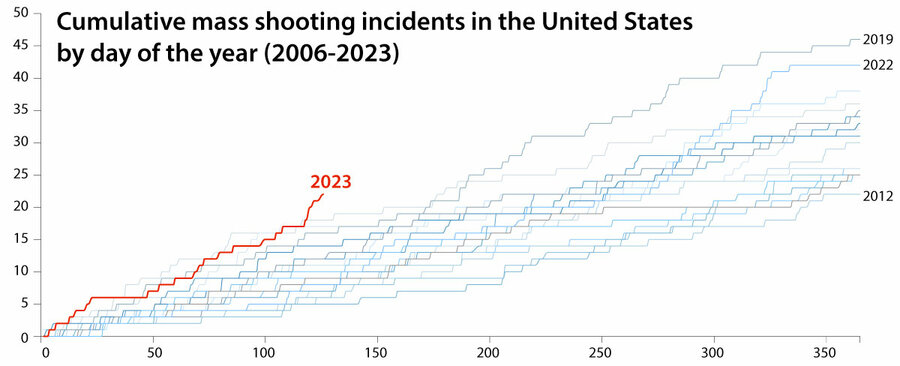

So much of American politics today promotes a profound sense of impotence – the inability to move entrenched forces, even a degree. With devastating frequency, mass shootings tragically underscore this fact.

The Monitor does not exist to advocate for any particular policy, but for the expansion of universal values such as compassion, freedom, responsibility, or honesty, to name a few. This can be accomplished in countless ways that defy partisan lines. Yet it is inescapable that mass shootings, while the result of many variables, are inextricably connected to America’s gun laws. Although mass shootings are not unique to the United States, their scope and frequency are.

We know deaths would rise if we loosened seat-belt laws or car safety regulations. Why are guns seen as different?

This past weekend, I felt that profound sense of impotence after the latest in America’s series of mass shootings. But here is where journalism can play a vital role. It does not need to tell us what to think. But it can keep us awake.

Falling into the indolence of despair must never be an option. To this end, the Monitor has put together a collection of stories to show that ways forward are possible and that problems remain entrenched only so long as we turn away or view the other side as the enemy. The special edition went out to all our subscribers this morning.

In Nashville, Tennessee, last month, more than 5,000 people linked arms, forming a chain 3 miles long that ended at the statehouse. Their demand: Do something. “This is not a political issue. It’s a public safety issue,” the nonpartisan coalition said.

So often, the product of entrenched politics is a loss of hope and agency. But that can be true only when we give up.