In a cruel twist, residents of Kherson who survived nine months of Russian occupation until liberation by Ukrainian troops are now subject to such hardship that many feel obliged to evacuate.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Ken Makin

Ken Makin

This afternoon, Morocco’s dream of reaching the World Cup final ended with a 2-0 loss to France. It was a historic ride – the first time an African team has ever made it to the semifinals. But the team started to capture my attention weeks ago after their 2-0 World Cup win over highly favored Belgium. After the match, the team kneeled in what has become a familiar tradition during Morocco’s improbable run to the semifinals.

A quote from coach Walid Regragui prior to the matchup against Canada also drew me in: “We hope to fly the flag of African football high.”

Mr. Regragui continued his praise of the continent after Morocco’s upset of Spain in the round of 16. “I am not here to be a politician,” he said. “We want to fly Africa’s flag high just like Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon. We are here to represent Africa.”

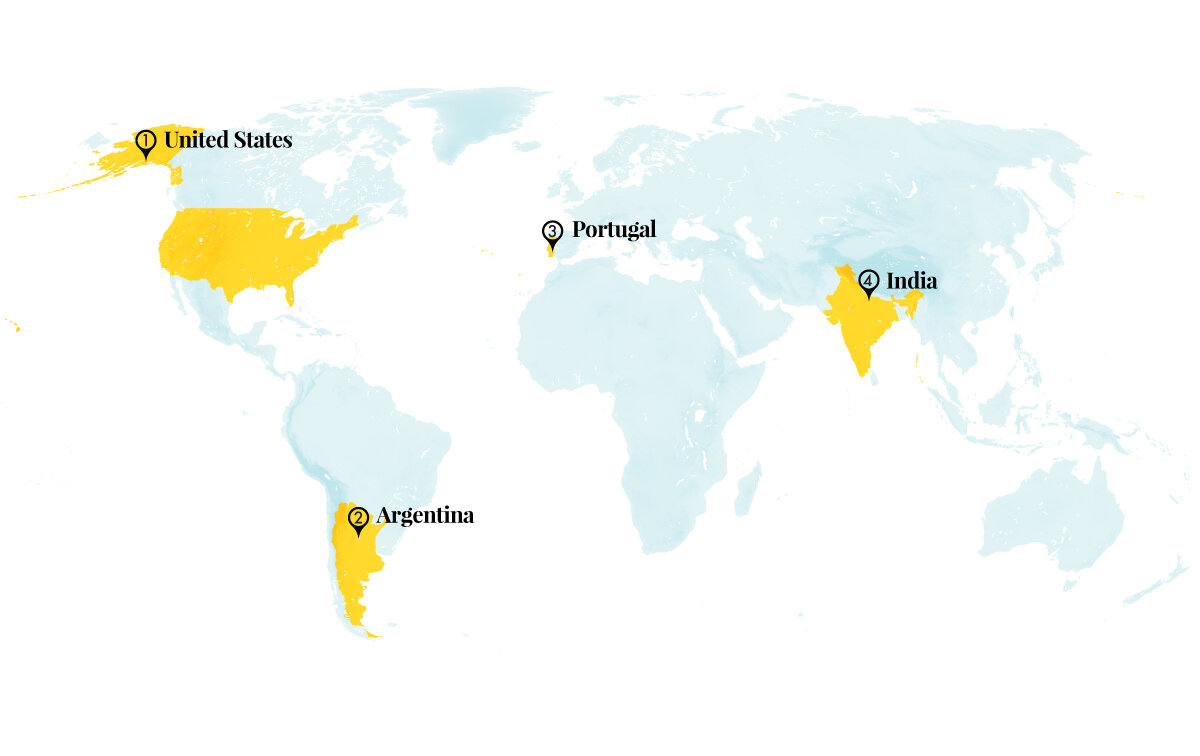

Mr. Regragui’s quotes have added perspective to what has happened on the field. I can’t help but notice all the dynamic players with African roots on various teams – France’s Kylian Mbappé, The Netherlands’ Memphis Depay, and Team USA’s Tim Weah come to mind. And while Mr. Regragui isn’t “here to be a politician,” his exaltation of Africa only adds to the compelling geopolitics of this World Cup.

That mix of sport and international affairs has been a controversial one, for sure. Should the games have been held in Qatar, considering how laborers have been treated? Why did FIFA strike down on-field protests in the name of human rights? Why don’t we talk more about the role of racism and colonization, not just on football teams, but across the globe?

To that end, Morocco’s tournament run has been a saving grace. The Atlas Lions have also uplifted the downtrodden, raising the Palestinian flag after wins.

A celebration of Africans and Arabs. A celebration of unity with worldwide reverberations. Morocco’s success is something that all of us can truly enjoy and embrace.