Hispanic heritage: Remembering a 9-year-old’s pioneering step

Clara Germani

Clara Germani

Before there was Brown v. Board of Education, there was Mendez v. Westminster.

This Orange County suburb is one of those postwar drive-by burgs that are an unremarkable blur at freeway speed.

However, the quiet stratifications of Westminster history are quite remarkable: Indigenous culture overlaid by vast 19th-century Mexican land-grant ranchos, then the fragrant citrus boom of the early 20th century. And – since the 1970s – it’s become one of the biggest concentrations of Vietnamese immigrants in the United States, known as Little Saigon.

But in the 1940s, a group of Mexican American families here waged a pioneering battle against the sorting of children by ethnicity – Anglo-American children to one school, Mexican American to another. The reason, a local official testified, was: “Mexican children have to be Americanized ... taught cleanliness of mind, mannerisms, dress.” Bracing inspiration for forced segregation.

Grade schooler Sylvia Mendez, who today in her 80s is still on the civil rights speaking circuit, was barred from a school close to the land her father ranched and sent to a “Mexican school.”

In 1943, Sylvia became the lead plaintiff in the case, which did not claim the segregation was racial discrimination (because Mexicans were legally considered white) but that the social, psychological, and pedagogical effects damaged Mexican American children.

They won. And Thurgood Marshall used the precedent in constructing his Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that in 1954 successfully established separate but equal education facilities for racial minorities as inherently unequal.

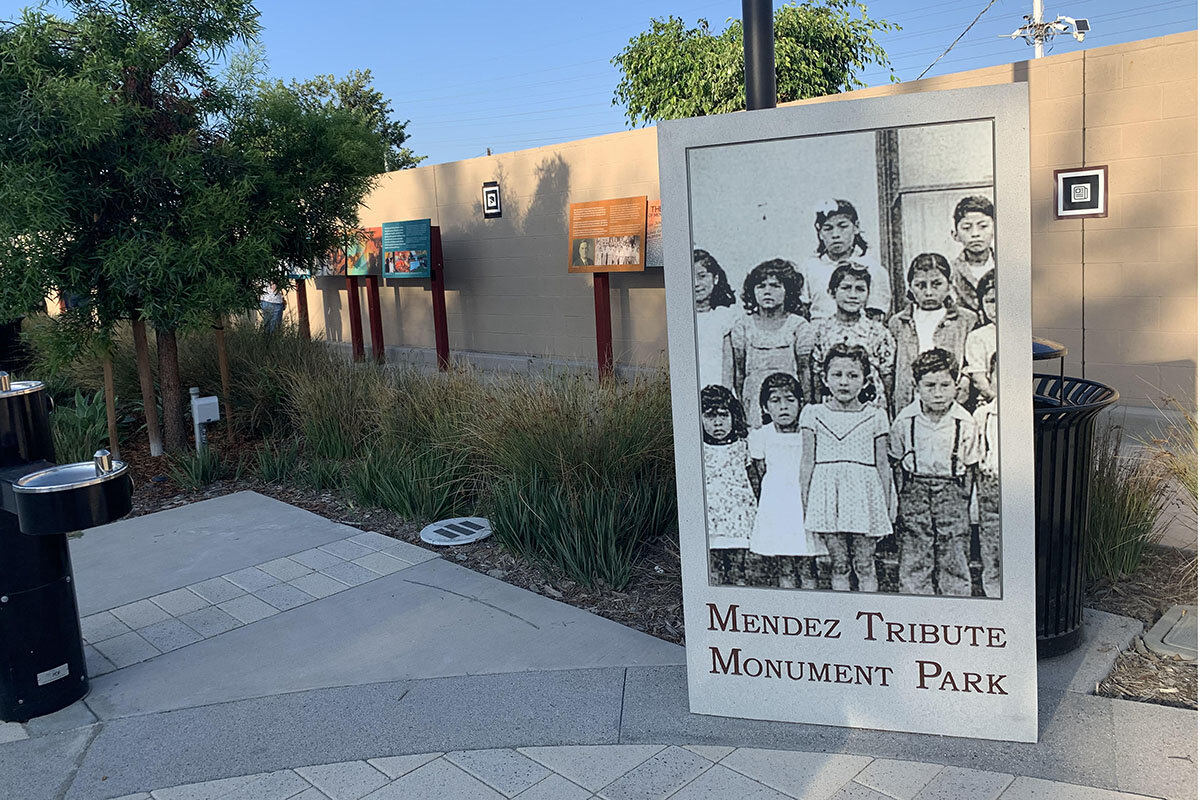

This fall, Westminster is opening the Mendez Historic Freedom Trail and Monument. It’s a creative oasis of landscaping, art, and historical interpretation commemorating the courage and perseverance of the families who won their desegregation case.

Last week, Jeff Hittenberger, Vanguard University professor of education and the creator of the trail’s interpretive panels, brought student teachers to see the nearly finished site.

Before his course, none of his students had heard of Sylvia Mendez.

One graduate student, Gilbert Angeles, noted that before he studied the Mendez case and talked with his mother about it, he had no idea she’d spoken only Spanish when she came to the U.S. from Mexico and rose from janitorial work to become the professional director of a mental health program.

Exiting the monument, Mr. Angeles gushed comparing the “sacrifice and perseverance” of Sylvia’s parents to his mom’s: “This is our history, too!”