Where adults might fret over uncertainty, children often see opportunity. We ask fifth graders about their visions for the future. Their answers are full of childlike innocence – but also are strikingly pragmatic and serious.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Lindsey McGinnis

Lindsey McGinnis

It was June 2020. COVID-19, economic turmoil, and police brutality dominated the news. Articles about combating “news fatigue” punctuated long bouts of doomscrolling. It wasn’t exactly an auspicious time to take on the progress beat.

And yet, my assignment was clear: As the Monitor’s Points of Progress reporter, I needed to identify a handful of credible progress stories every week.

It felt like searching for a piece of hay in a pile of needles. For every hint of progress, I encountered at least 30 distressing headlines. It was hard to accept that those glimmers of growth could hold much weight in the midst of such overwhelmingly grim news. But over time, I began to recognize them as fuel for hope.

I quickly learned to spot the telltale signs of progress – and that “perfect progress” doesn’t exist. So much is subjective, contentious, fragile, or incremental. The march toward progress rarely comes in giant leaps. But each step – even the false starts – can help build forward momentum.

There’s no doubt that these progress reports matter. More than half of Americans say the news causes them anxiety or sleep loss, according to a pre-pandemic survey by the American Psychological Association. Stories that touch on potential solutions to the world’s problems, however, have an empowering effect on audiences.

It’s not about turning a blind eye to hardship – it’s about making sure we don’t let it obscure our sense of reality.

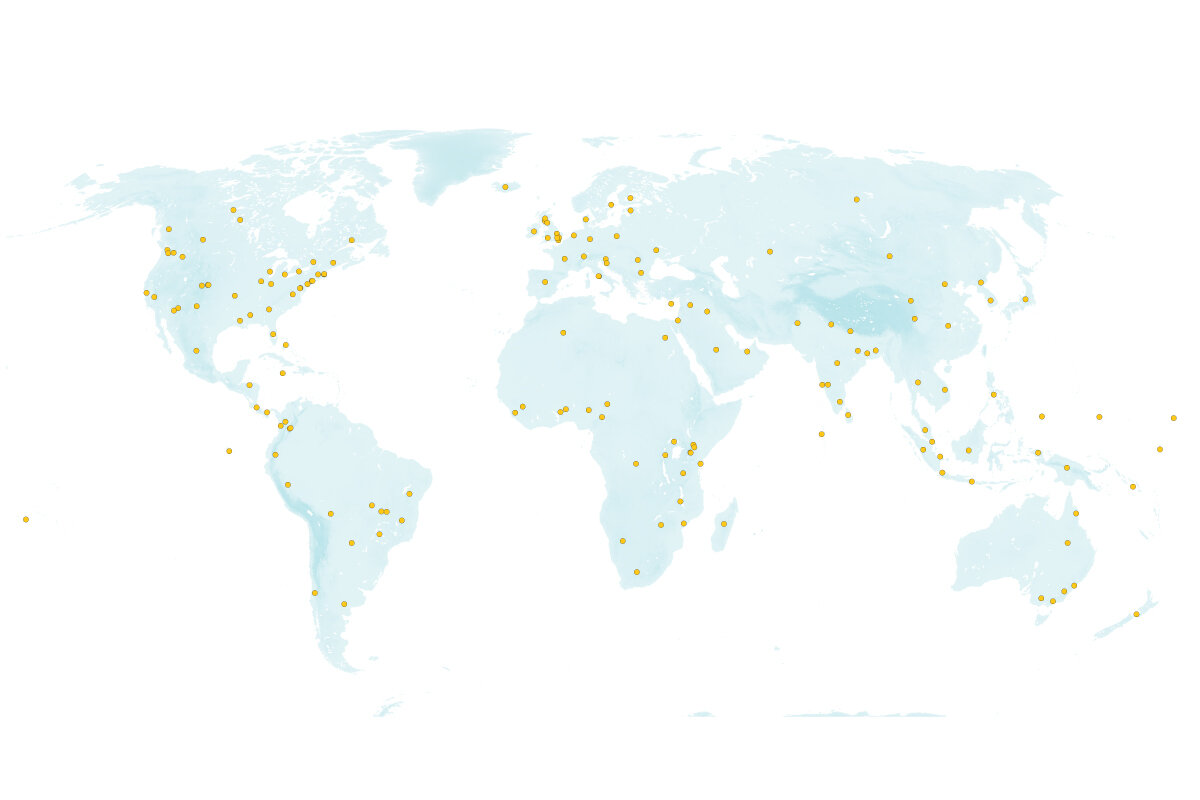

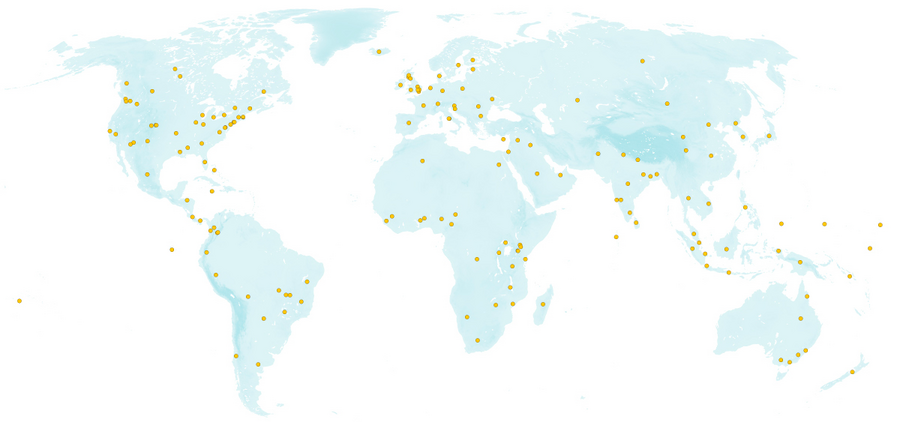

As we begin 2022, many of the struggles of the past year still loom large in our memories. But we also found 257 signs of progress worth highlighting in 2021. This week’s feature explores key themes from last year, and underscores the biggest takeaway from my 18 months on the progress beat: There’s always a reason for hope, if you look for it.