Public views on capital punishment are shifting rapidly, with more states moving to ban it. As with many issues, the change is being driven largely by millennials.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

“Finding light in the darkness is a very American thing to do,” President Joe Biden told the nation last night as he marked a year of pandemic shutdown.

For Wendell Allsbrook, a butcher in Washington’s tony Georgetown neighborhood, those first flickers were almost extinguished before they could really shine.

Mr. Allsbrook had spent years learning the gourmet meat business, working for others, saving, studying, wooing investors, meeting purveyors. Finally, he opened his store – on March 9, 2020. Two days later, COVID-19 closed everything.

But he didn’t give up. He regrouped, surviving early losses by selling via delivery and pickup.

“As one of the few Black-owned businesses on the west end of the city, Allsbrook was determined to stay open while demonstrators advocated for Black lives,” writes Petula Dvorak in The Washington Post.

He also hopes to be a model for his teenage sons, and give back to his community, mentoring young people who grew up rough like him.

Georgetown Butcher’s prices are not for the faint of heart. Japanese wagyu A5 rib-eye (currently out of stock) sells for $200 a pound. The signature salmon is $23 a pound. A whole chicken is $26.

With millions turning to food banks, the inequities are stark. President Biden’s $1.9 trillion relief plan will help: Economists project a one-third reduction in the number of Americans living in poverty.

But for Mr. Allsbrook, the “light in the darkness” came by identifying a market and then serving it. A second location opens soon.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Graphic

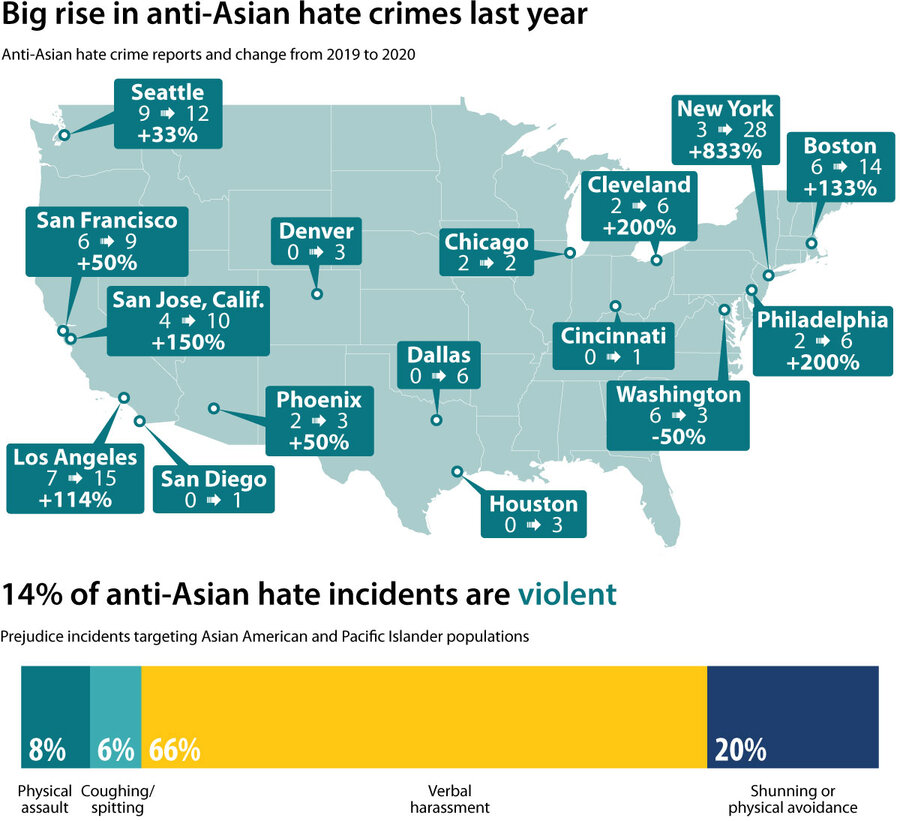

‘Tip of the iceberg’: Mapping the pandemic jump in anti-Asian hate

More than one year into the coronavirus outbreak, it’s becoming clearer that the pandemic has unwelcome side effects that go beyond public health.

Surveying 16 major American cities, researchers at the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism (CSHE) at California State University, San Bernardino recently noted an alarming spike in hate crimes against Asian Americans in 2020.

Even as overall hate-crime reports fell 7%, those against Asian Americans rose by almost 150%. Incident reports of anti-Asian prejudice also grew more violent, with 15% involving physical assault or spitting. Around two-thirds included verbal harassment or threats.

“We don’t often see these kinds of spikes,” says Brian Levin, director of the CSHE. And due to vast underreporting – a product of cultural and linguistic barriers, he says – “all we’re doing is measuring the tip of the iceberg.”

The rise fits a pattern of ethnic groups facing discrimination in America, says Professor Levin. Around 2010, hate crimes against Latinos jumped after a raft of unauthorized border crossings. In the middle of the decade, those against Muslims rose, following the San Bernardino shooting in California.

“This is another unfortunate rotation that often comes about from the combination of a catalytic, fear-inducing event, along with stereotyping and conspiracizing by political leaders and others,” says Professor Levin.

In 2020 the culprit was the coronavirus pandemic, and former President Donald Trump’s rhetoric in particular, he says. Calling COVID-19 the “China virus” or “kung flu,” for example, can stoke public resentment.

But if rhetoric can harm, it can also heal. It’s no coincidence, Professor Levin says, that hate crimes receded for multiple days after Mr. Trump tweeted last March that Asian Americans aren’t to blame for the virus and that protecting them is “very important.”

In a speech Thursday marking a year of the pandemic, President Joe Biden used his podium to call fresh attention to the issue, saying of hate crimes against Asian Americans, “It’s wrong, it’s un-American, and it must stop.”

( 6 min. read )

Even as Arab voters increasingly embrace their voice in Israeli democracy, their current top concern, violent crime, is one at least partially rooted in decades of inequities.

( 6 min. read )

Deploying new renewable energy technology is critical for energy conservation. But just as important is getting communities to embrace its adoption at the grassroots level, as the island of El Hierro has.

( 4 min. read )

Music is universal – all cultures create it. Our columnist wonders if the Grammy Awards, airing this Sunday, can move beyond a pattern of exclusion to honor that diversity.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

The people of Niger live in a sweltering sandscape on the southern reaches of the Sahara known as the Sahel. The country is surrounded by neighbors with overlapping Islamist insurgencies. Hundreds of thousands of refugees have streamed across its borders in recent years. Hundreds of thousands of its own people are internally displaced by fighting between extremists and the military. Agriculture, the backbone of its economy, is at risk from climate change.

All of this makes Niger an unlikely indicator for an underlying shift in Africa despite the continent’s many conflicts and anti-democratic leaders.

In the past decade, Niger has been able to maintain robust economic growth, shaving the proportion of the population living in extreme poverty by nearly 10%. Both school enrollment and life expectancy are up. Even more significantly, when results from a presidential runoff election were announced last week, President Mahamadou Issoufou, who has been in power since 2011, accepted defeat and vowed to step down next month.

A peaceful transfer of power would mark a first for a country that has gone through seven constitutions and a military coup since independence from France in 1960. Yet Mr. Issoufou’s concession is no isolated event. A popular hope for more peaceful transfers of power in Africa has taken hold.

In the island nation of Seychelles, for example, President Danny Faure accepted defeat in an election last October, ending 43 years of one-party rule. Three days later he attended his opponent’s inauguration. The incoming president, Wavel Ramkalawan, called Mr. Faure his friend and appointed him an ambassador.

The norm in Africa is still stark. Sixteen countries face sustained armed conflict, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. The latest survey by the watchdog group Freedom House shows 23 of Africa’s 54 nations are “not free,” while another 21 are only “partly free.”

But if Africa’s rulers remain stuck in authoritarian ways, its people are showing more signs of pushing back. A survey done for UNICEF and the African Union last year found an overwhelming majority of young Africans (91%) would like more say in political decisions that shape their lives. Currently 59% say they lack access to policymakers. And in another survey by the Ichikowitz Family Foundation, 86% of young people in 14 African countries say the democratic values of Nelson Mandela are still relevant for them today.

Such sentiments are evident in many African countries. In Senegal and Uganda, opposition supporters have lately launched rolling protest campaigns against presidents who have changed their countries’ constitutions or arrested their political opponents to remain in power. In Tunisia and Ethiopia, fear of political fragmentation has prompted urgent calls for dialogue among rivals.

The decision by Niger’s president to accept defeat has won quick praise. Last week he was awarded a prize for “achievement in African leadership” by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Although the award is meant to be given annually, it has been withheld more often than bestowed over the last 15 years for lack of worthy recipients. In announcing the award, former Botswana President Festus Mogae said “a seed has been planted” in Niger. The country’s peaceful transition, he said, “will encourage the population to be more demanding of future leaders.”

More Africans want to claim their moral right to basic freedoms, equality, and rule of law. Despite ongoing instability in Africa, Niger and Seychelles are the latest examples of a public yearning for such ideals. Amid the violence and crackdowns, those voices are being heard.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

What does it mean to think God’s thoughts? For a woman who has experienced both racism and sexual harassment, digging into that very question lifted her out of a dark place and brought peace, confidence, and clarity about how to effectively confront such injustice.

A message of love

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back on Monday, when staff writer Ann Scott Tyson looks at the meaning of “patriotism” as Beijing seeks to impose its definition on Hong Kong.