As uncertainty about COVID-19 and the limits of online learning muddy disputes between city officials and teachers unions about reopening, the clear reveal is systemic inequality.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Clayton Collins

Clayton Collins

West Virginia and pharmaceuticals have a dark association. The state sits at the epicenter of America’s cruelly persistent opioid epidemic, with an unwelcome top ranking in overdose death rate.

Victimhood can be an easy narrative to extend. West Virginia anchors a region that’s often cast as “uniquely tragic and toxic,” as Elizabeth Catte wrote in her 2018 book, “What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.”

But as she and others point out, it’s a story that’s sorely incomplete.

We reported in 2017 on how one West Virginia city paired law enforcement with compassionate outreach to attack the cycle of hopelessness that fuels addiction.

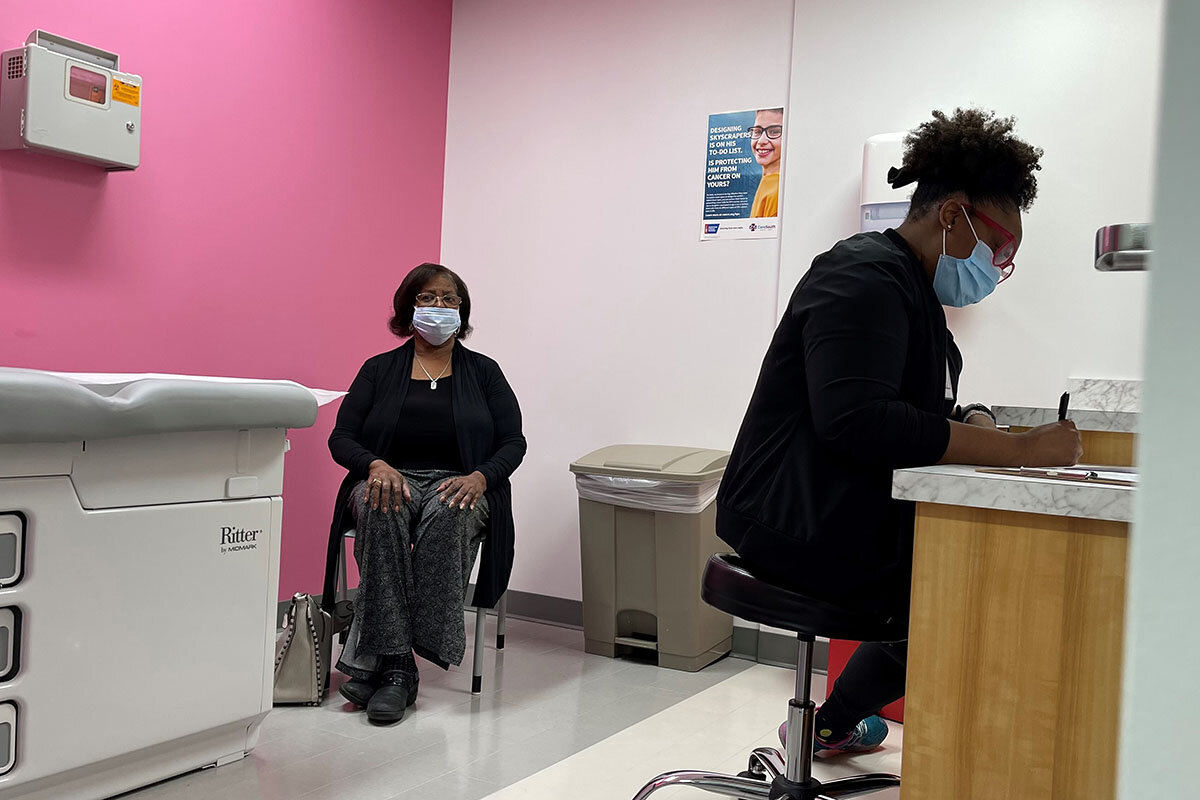

Now, with worldwide responses to a coronavirus pandemic ranging from disjointed to stunningly ad hoc, West Virginians are applying a spirit of self-determination to making sure COVID-19 vaccines get to those who want them.

Last week it rolled out a tech partnership that curbs waste by alerting eligible vaccine-seekers when no-shows make doses available. Before that, the state chose to lean on its small, independent pharmacies, more nimble and arguably more incentivized than the big, sometimes understaffed chains other states use.

“As my uncle always told me,” one West Virginia pharmacist told the AP, “these people aren’t your customers, they’re your friends and neighbors.”

Among U.S. states, West Virginia was first to meet initial needs in its nursing-care facilities. That’s a welcome top ranking in responsiveness and humanity, and a clear sign of agency.

“Our album is filled with images of people who suffered,” writes Ms. Catte, “but also people who fought.”