Divided by geography and culture, and relying on different media sources that often emphasize different facts, Americans are experiencing the pandemic through sharply divergent partisan lenses.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Peter Grier

Peter Grier

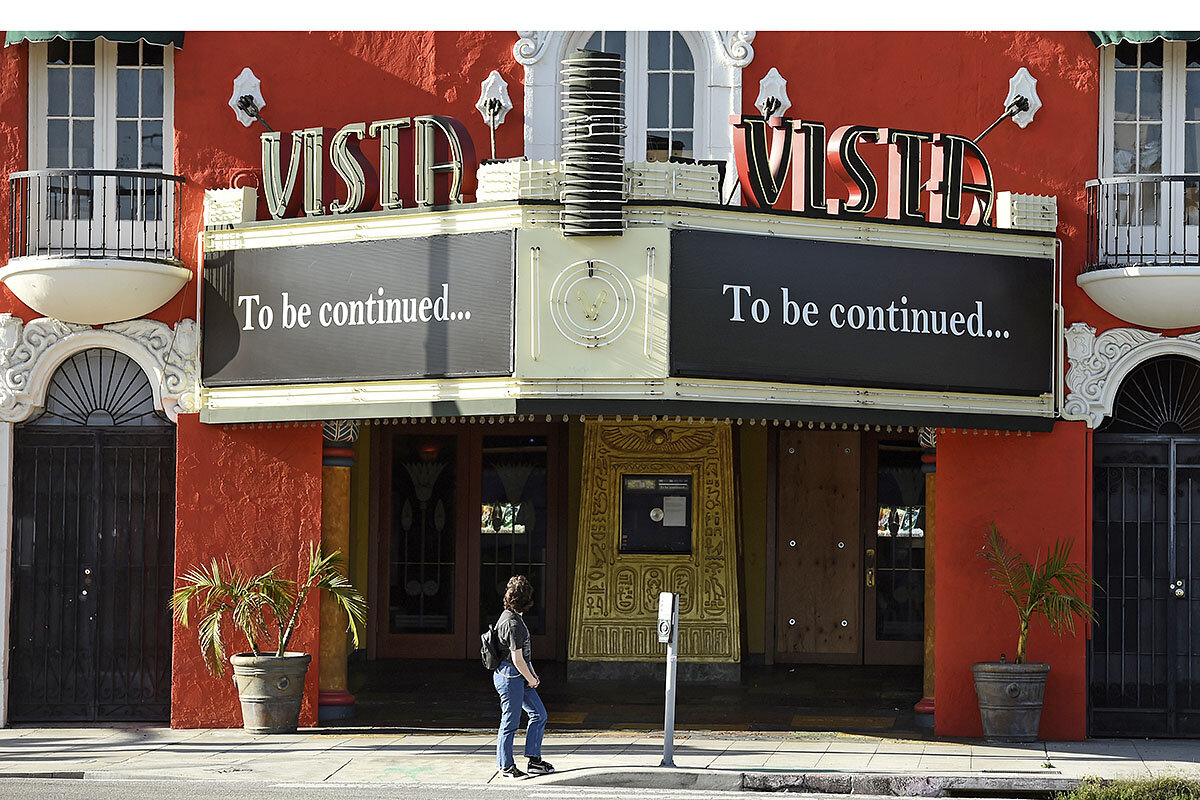

Today’s issue looks at how partisanship now affects opinions about practically everything, from masks to Dr. Fauci; stand-your-ground laws and Ahmaud Arbery’s shooters; the struggle to determine how immunity to COVID-19 might work; whether some companies will move toward caring for stakeholders instead of only shareholders; how Vermont country stores are needed now more than ever; and when we might see a movie in a theater again.

The news can be pretty dark nowadays. But even on the darkest days you can spot glimmers of renewal.

Consider England’s Sturminster Newton Mill. It’s an ancient L-shaped building at a curve in the River Stour in Dorset. That’s a county of fields and chalk hills in the country’s southwest that was home and inspiration to the famous novelist Thomas Hardy.

There’s been a mill at the site for at least 1,000 years. The current one dates back to 1611. It’s been owned by a local heritage trust since 1994.

For years the mill has been run as a working tourist attraction. It hosts fun fairs and picnics and sells small bags of the mill’s authentically-ground flour as souvenirs. But there are no tourists nowadays, of course. Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic the mill’s doors have been closed.

But the millstone is still there and turning. So miller Peter Loosmore – whose grandfather held the same position 50 years ago – had an idea. Flour has been in short supply during the lockdown, as baking by stay-at-home cooks has spiked. Why not resume commercial operation?

They started in late March, distributing through local grocers. They’ve already run through the ton of grain purchased for tourist season and are looking for more to fill their 1 1/2 kilogram bags.

“In one way we have an advantage over the bigger mills, which are used to selling large sacks to the wholesale trade and don’t have the machinery or manpower to put the flour into small bags,” Mr. Loosmore told a local paper, The Bournemouth Daily Echo.

Hardy probably would have approved of this revival. The Victorian author once lived only a few yards from the mill, and wrote one of his most popular novels there. Its title was apropos: “The Return of the Native.”