Revive economy with virus-immune workers? Not so fast.

Loading...

More than 327,000 people in New York have tested positive for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Of these cases, more than half are in New York City.

Jayne Oh isn’t one of them. But she’s convinced that she came down with COVID-19 in mid-March, just as the city went into lockdown. “It came on quite suddenly,” she says.

Ms. Oh, a marketing analytics consultant living in Brooklyn, stayed in her bedroom for three days. Her doctor advised her to isolate herself from her husband and two young children but not to go to the hospital, and within days she had begun to regain her health.

Why We Wrote This

In the early weeks of stay-at-home orders, policymakers and the news media voiced hope that immunity tests would become a major tool for reopening the economy amid a pandemic. Now the narrative is shifting.

Ms. Oh is one of an untold number of New Yorkers who have had COVID-19-like symptoms and recovered, but were never tested.

The question matters not just to Ms. Oh – who wonders if she now has immunity to the virus – but to cities and states considering how to reopen. Immunity could influence how communities reopen, and how quickly they do so. A pool of immune workers, for example, could be a powerful tool to help reopen safely.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

But first officials need to understand whether COVID-19 immunity exists and how it works. And that process is proving difficult.

Medical experts and clinicians understand why policymakers anxious to find a path back to economic vitality have talked up the idea of immunity. But, says Kamran Kadkhoda, who directs the immunopathology lab at the Cleveland Clinic, a hospital in Cleveland, Ohio, “we have to do this [reopening] in a prudent manner.”

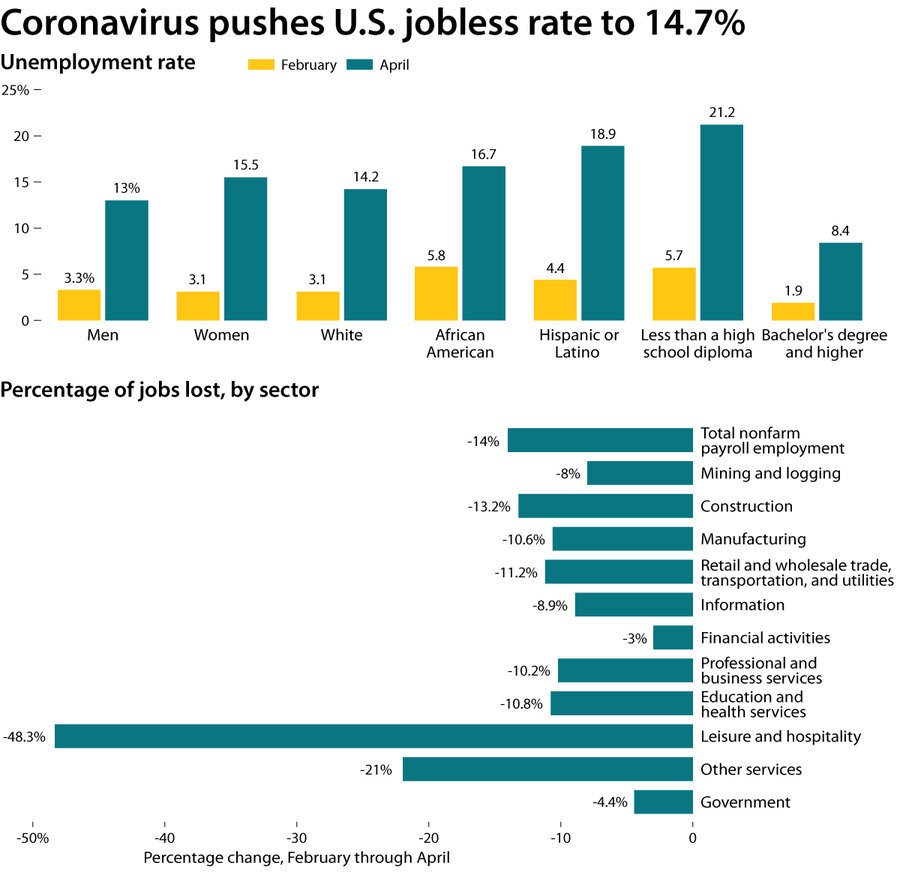

One test for potential immunity is a blood screening to look for antibodies that reveal a previous viral infection. The promise of antibody testing has captivated political and business leaders in the U.S. and elsewhere who hope it can help them revive their pandemic-crushed economies. In the U.S. alone, the unemployment rate surged to 14.7% in April as precautions against the virus stalled business activity.

From hospitals in Michigan to college campuses in Arizona and software firms in California, antibody testing has already begun in an attempt to sort those who have and haven’t been infected. Cities and states are buying testing kits and partnering with research labs to screen residents.

But the flurry of interest in antibody testing as a shortcut to reopening hard-hit cities like New York has given way to humility. Gov. Andrew Cuomo initially seized on antibody tests as a way to get people back to work and children back to school. By last week, though, he had cooled on the idea after the World Health Organization warned there is no evidence of protection from reinfection. “There are a lot of unknowns about these antibodies,” says Dr. Kadkhoda.

That doesn’t mean nobody has acquired some immunity to COVID-19; in all likelihood the virus acts like other coronaviruses that infect humans, with some immunity for those who have had it, says Paula Cannon, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Southern California’s medical school.

But how strong any immunity is and how long it lasts is unclear. “The only way we’ll know is the numbers over time,” she says.

The wait for clarity on this, coupled with the absence of a vaccine or effective medical treatments for the disease, hangs over nascent efforts to reopen the U.S. economy. While some voters chafe at social restrictions, a majority in polls express fear at a hasty reopening amid a pandemic, adding to the pressure on political leaders.

Goals of antibody testing

Antibody testing isn’t just about finding out who might have immunity. It can help in other ways. Epidemiologists want to track how far the virus has spread, how many people unwittingly had it, and to calculate the fatality rate. Initial tests in hard-hit places like New York City and northern Italy suggest that the number of confirmed cases is a fraction of the actual number.

But several countries, including the United Kingdom and Germany, have also explored the idea of “immunity certificates” for those who test positive for antibodies, allowing them to go back to work first.

Last month, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, said that the U.S. government was discussing a similar program. “I think it might actually have some merit, under certain circumstances,” he told CNN.

No country has issued immunity certificates, and analysts point to a raft of practical, legal, and ethical concerns, such as the incentive for workers to deliberately get infected or to falsely obtain certificates so they can keep their jobs. Germany’s health minister said Monday that the government would first consult a national ethics council before proceeding.

Another concern is the accuracy and consistency of antibody tests. The U.K. recently ordered 2 million home test kits from China that Prime Minister Boris Johnson said could be “a total game changer” in finding out who had immunity, only to scrap the tests as unreliable.

More than 100 different tests are now being sold in the U.S. without government approval under emergency rules, and researchers at the University of California’s San Francisco and Berkeley campuses found some produced over 10% false positives when used on pre-pandemic blood samples from patients who were thought not to have been exposed. Others showed false negatives from former COVID-19 patients. On Monday, the Food and Drug Administration said it was tightening rules on which tests could be sold.

Until we know more, antibody tests won’t provide certainty as to who can safely be exposed to the virus, says Tom Frieden, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “If people take actions based on inaccurate tests, or if they presume that antibodies reflect immunity and they don’t,” they could contribute to another wave of infections.

“We all want .... normalcy”

At first, Ms. Oh figured she, her husband, and two small children must have immunity, which was a comforting idea during lockdown until she read up on the issue. Now she plans to get an antibody test at a local clinic to see if she’s positive.

“I [would] know that I had it, I’m OK, and I survived. I would feel more ready to get back out there,” she says. Six or more weeks into the lockdown, she says “we all want to take some steps towards normalcy, what we had before.”

Antibody tests can offer “a certain peace of mind,” even though a positive result provides no guarantee of immunity, says Dr. Cannon. “I think there’s value as an individual, if you understand what the result means.”

New York City Council member Ritchie Torres knows he had COVID-19. He tested positive in March and self-isolated in his apartment in the Bronx district he has represented since 2013. It was a relatively mild case, and he was soon back at work remotely, shoring up services in what has become the city’s coronavirus epicenter.

Mr. Torres knows that he can’t assume he has immunity, so he’s not visited his mother, who lives alone, out of caution.

But he also knows that every day that New York is closed for business, the city sinks deeper into a financial black hole. The city’s comptroller said Tuesday that 1 in 5 New Yorkers is likely to be out of work by the end of June and that it would take years for employment to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

“The whole ecosystem of New York City is at risk,” says Mr. Torres.

He understands the risk of antibody testing that could give New Yorkers who test positive a false sense of security. For now, he says, there is no failsafe option. “We [would] have to be honest and say that we’re opening the economy based on a presumption of immunity rather than a knowledge of it.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.