Can a candidate message one way before primaries, and another in the general election? For candidates trying to reach a divided nation, the tension in that time-honored approach is deepening.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Clayton Collins

Clayton Collins

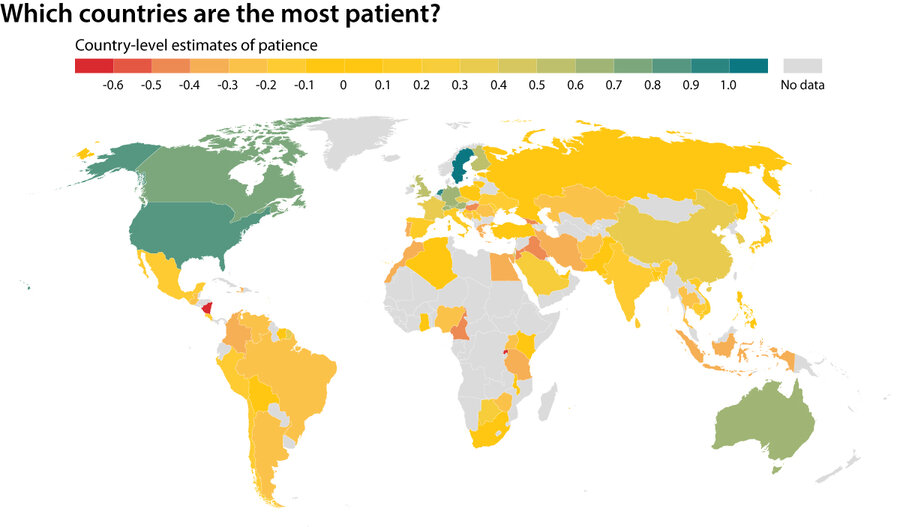

Today we look at the thinking behind a political lane choice, young farmers on the Great Plains, a (perhaps surprising) finding about Americans’ patience, a digital front door for church, and a magical space for storytelling.

First, small signs of a shift that should encourage anyone reading this: Young adults – and even some future young adults – appear to be expressing a real interest in real news.

That might not be altogether new. But at a time when “news avoidance” is considered a broadly applied practice, the U.S. generation to which global policies and actions matter most – and whose number is expected to eclipse that of boomers this year – is becoming one that is full of active news seekers.

A report this month from the Knight Foundation found that 88% of surveyed Americans ages 18-34 access news at least weekly, including 53% who do so daily. More important, many consider themselves attuned to the leanings of their sources, a critical skill for sifting for bias on everything from climate change to mass shootings.

Young newsies may be less brand-loyal and more inclined to do their own broadly sourced curation than others, but news quality is as important to this cohort as it was for those who came before, writes Dan Kennedy for WGBH.

That’s hardly U.S.-exclusive. In Britain, a 2018 report from the National Literacy Trust found half of young people it surveyed to be worried about agenda-driven reporting. Organizations like NewsWise, supported in part by the NLT, are working with some of those who are next up – students ages 9-11 – on news literacy.

They have so many questions,” writes Angie Pitt, the organization’s director, in The Guardian, “let’s give them the time and the opportunity to ask them.”