Cannes debuts something different: Lower tolerance for sexual violence

Loading...

| Paris

At this year’s Cannes Film Festival, one member of France’s glitterati has been notably missing from the red carpet: Gérard Depardieu.

Once one of France’s most prized cultural icons, Mr. Depardieu was found guilty of sexual assault on May 13, the festival’s opening night, in what Cannes jury President Juliette Binoche called “interesting timing.”

However coincidental the verdict’s announcement, the shift at Cannes in regards to sexual violence is clear. French cinema has been forced to reconcile with its decadeslong problem of ignoring sexual violence in the industry as several actors and directors, alongside Mr. Depardieu, have fallen from grace in the past year. The festival has had little choice but to respond.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onJust a few years ago, the Cannes Film Festival was feting male actors and directors even as they were credibly accused of sexual abuse by female peers. Now, the tides appear to have shifted on the behavior the French film industry tolerates.

On opening night, host Laurent Lafitte paid tribute to French actor and activist Adèle Haenel, who in 2020 walked out of the César Awards ceremony to protest honors for director and convicted rapist Roman Polanski. The festival also decided to bar a French actor from walking the red carpet over rape allegations.

France’s film industry has made significant progress in breaking the silence around sexual violence since the #MeToo movement broke through in 2017. But a recent parliamentary inquiry into the inner workings of French cinema found that sexual violence was “systemic, endemic, and persistent,” and enabled a culture of impunity.

How much does Mr. Depardieu’s conviction and the progress shown at Cannes indicate change across the industry as a whole?

“It’s no longer possible or desirable to excuse bad behavior,” says Erwan Balanant, the rapporteur for the parliamentary inquiry into sexual violence in French cinema. “Even if you’re a genius, you live in our society and there are rules to follow.”

“Artists are not above the law”

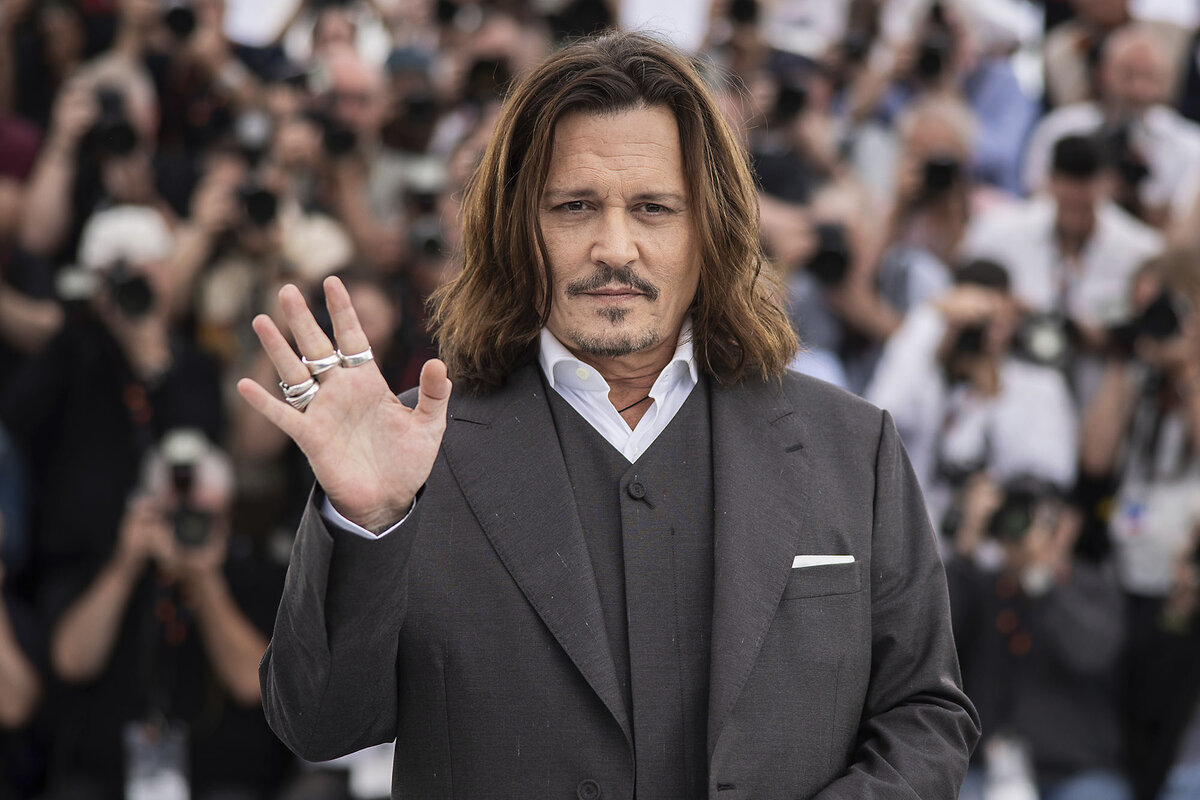

It was only two years ago that Johnny Depp’s presence at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival split the French film industry.

At the time, he had been spared a conviction for allegedly sexually and physically abusing his ex-wife, actor Amber Heard. But not only did the festival roll out the red carpet to Mr. Depp, who came to promote his starring role in “Jeanne du Barry”; the actor received a seven-minute standing ovation from the audience.

But in an open letter, 123 actors condemned Cannes for failing to take a stand against sexual aggressors like Mr. Depp, and instead continuing to attempt to “separate the art from the artist.”

“There is an older generation of French actor who thinks the world belongs to them, who easily objectifies women,” says Thelma, a Paris-based screenwriter whose complaints against a co-worker for sexual harassment in 2020 were ignored by film producers. She asked to use a pseudonym out of concern for reprisals. “There are also plenty of people who have been just as willing to cover up the abuse.”

In the past year, however, the industry has become less eager to extend a warm welcome to those implicated in abuse trials, and that has started on the festival trail.

This year, the Cannes Film Festival barred actor Théo Navarro-Mussy from walking the red carpet after three former partners accused him of rape. Festival director Thierry Frémaux justified the decision by saying, “There is an appeal, therefore the investigation is still active.”

Festival President Iris Knobloch also invited victims of sexual abuse to participate in a roundtable discussion about how the industry can evolve. Last Thursday at ACID Cannes, an independent film event that runs parallel to Cannes, one of ACID’s vice presidents was suspended after being publicly accused of sexual assault during a Cannes roundtable.

Accused sexual abusers have not been shunned entirely, however. At another parallel Cannes event hosted by Better World Fund, Kevin Spacey received a lifetime achievement award. Mr. Spacey has been accused of sexual assault by multiple men, including some who were teenagers at the time of the alleged abuse.

Beyond Cannes, the César Awards (the French equivalent of the Oscars) have barred any nominees who were convicted of or under investigation for sexual assault. In February, director Christophe Ruggia was sentenced to four years in prison for sexually assaulting Ms. Haenel, the actor, while she was a teenager.

“What happened with Depp in 2023 would no longer be possible today,” says Geneviève Sellier, professor emeritus of film studies at Bordeaux Montaigne University in Pessac, France. “This past year has been essential in raising awareness of the systemic sexual violence in cinema ... and the realization that artists are not above the law.”

A sea change in French cinema?

Much of that awareness is thanks to a handful of French actresses who helped launch France’s #MeToo movement. In 2019, Ms. Haenel’s revelations that Mr. Ruggia had assaulted her as a minor rocked the industry. Since then, several French actors and directors have been implicated in similar cases. In 2024, actor Judith Godrèche accused high-profile directors Jacques Doillon and Benoît Jacquot of raping her as a minor.

At the 2024 César Awards, Ms. Godrèche gave an impassioned speech, denouncing the “level of impunity, denial and privilege” in the industry. Later at Cannes, she screened her short film, “Moi Aussi” (“Me Too”), about breaking the silence around sexual violence.

Ms. Godrèche’s activism pushed forward a parliamentary inquiry into abuse in the industry, which concluded this past April that French cinema needed to be “cleaned up and made safe.” The report offered 86 recommendations to the industry in order to stop the cycle of oppression and abuse.

The inquiry is already starting to have an effect on the industry. Starting in January 2025, French film crews will be required to attend a training on the prevention of sexual harassment and violence if they want to receive financial aid from the CNC, France’s national film board. The CNC provided €314.5 million ($354 million) in aid to French productions in 2024.

The CNC, as well as the French screenwriters’ guild, have also put in place a special unit to hear sexual harassment claims. And starting in the fall, France will launch a training program for intimacy coordinators, a profession that remains underused in the industry.

Industry insiders say French cinema is in the midst of a sea change. Thelma, the screenwriter, says that what took place even just one year ago would not be acceptable today. That sentiment is reflected in opinion polls, which show that a steep majority of the French are sympathetic to women who break the silence on sexual violence, and consider them courageous.

Still, the film industry is only one piece of French society, and insiders say that, unless life can truly imitate art, the fight to be heard and to stop sexual violence continues.

“We’re in an explosive moment, full of emotion,” says Hélène Merlin, who wrote and directed the 2025 film “Cassandre.” “What we need now is to stop and think, talk to one another, and take responsibility. That will lead to a real evolution.”