Why do young people so often seem to be at the front of protests? Maybe it’s the sense that their futures are the ones most at stake – and that’s particularly true in Hong Kong today, as Beijing’s control intensifies.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

Sometimes, good news quietly gets better.

Last year, Monitor staff writer Christa Case Bryant reported on a city in West Virginia that cut its opioid overdose rate in half, thanks to compassionate outreach for those struggling with addiction. The idea was simple: follow up with every survivor within 72 hours, sharing resources to help them get their lives back on track.

The Quick Response Team (QRT) was a relatively new initiative of Huntington, West Virginia. The results were dramatic for a city dubbed the epicenter of the national opioid crisis.

A year later, we checked back in. Not only has their success held steady, the average overdose rate in 2019 so far has been lower than in 2018. Of 1,180 individuals they’ve reached out to, they’ve been able to connect with 577, and 171 have gotten into treatment.

They’ve also added a faith-based component with local faith leaders – including a Baptist preacher, a rabbi, and an Episcopalian priest – joining a representative from EMS, the police department, and a treatment provider on each visit.

“I had one of the faith leaders say, ‘I offered to pray with one of the individuals,’” says QRT coordinator Connie Priddy. “He was so proud. He said, ‘I’ve never had anyone refuse to pray with me.’”

They have also been a support to team members, she adds. For all their success, the work can be heavy at times. Recently she saw a team member move a client’s folder to the bottom filing cabinet drawer after the individual died, and felt the solemnity of the moment. “They’ve worked hard, they know these people ... and now they’ve passed away,” she says. “Having those faith leaders there as support for them has really been great for the team.”

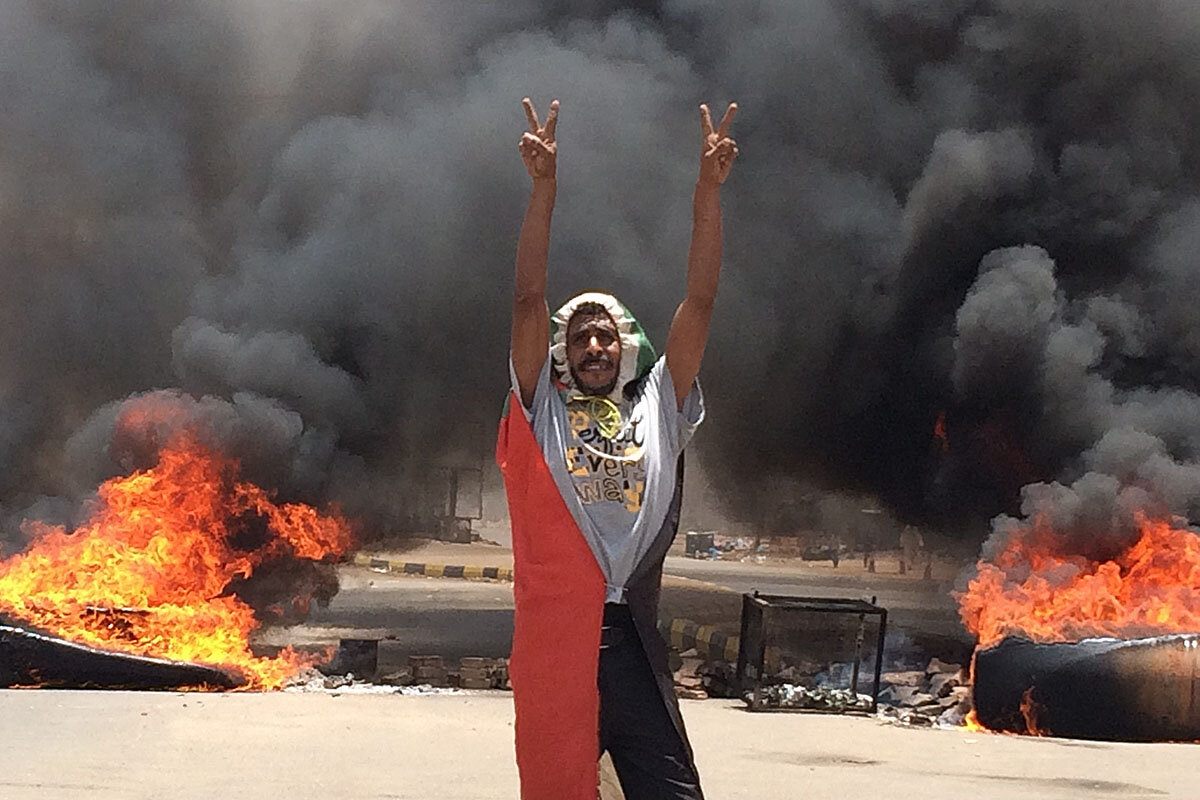

Now for our five stories of the day, featuring two countries where protesters are demanding freedom in the face of violence and a new kind of homebuying that has community built in.