Some see Bernie Sanders as too liberal and uncompromising to be president. But his track record as mayor reveals a pragmatic side.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Peter Grier

Peter Grier

What good is democracy?

That’s a question that’s been on my mind this week as I wrapped up the latest in the Monitor’s series “Democracy Under Strain.” (This one’s about the power of voting.)

When you focus on the faults, it’s easy to wonder about the system’s future. And right now America’s democratic government seems to be shedding nuts and bolts.

But democracy at its best is a system that allows open discussion of differences and then their resolution. It’s a way to manage conflict without actual fights.

New Hampshire showed that this week.

The issue was fraught: whether to abolish the death penalty. Both sides had heartfelt positions. Those who wanted to keep the penalty framed it as support for law enforcement. Those in favor of abolition cited the disproportionate number of minorities on death row and the risk of executing innocent people.

The result was close. Republican Gov. Chris Sununu is a staunch death penalty supporter. He’d vetoed an earlier repeal bill. Then on May 30 both the state House and Senate overrode his veto by one vote.

New Hampshire became the 21st state to ban capital punishment.

One quote stood out as reflective of democratic values. Before casting his ballot, Republican state Sen. Herbert French said he supported law enforcement personnel and their families. But he said he’d vote against the death penalty.

“My vote will be made because this vote is about our state and about what kind of state we are all going to be part of,” said Senator French.

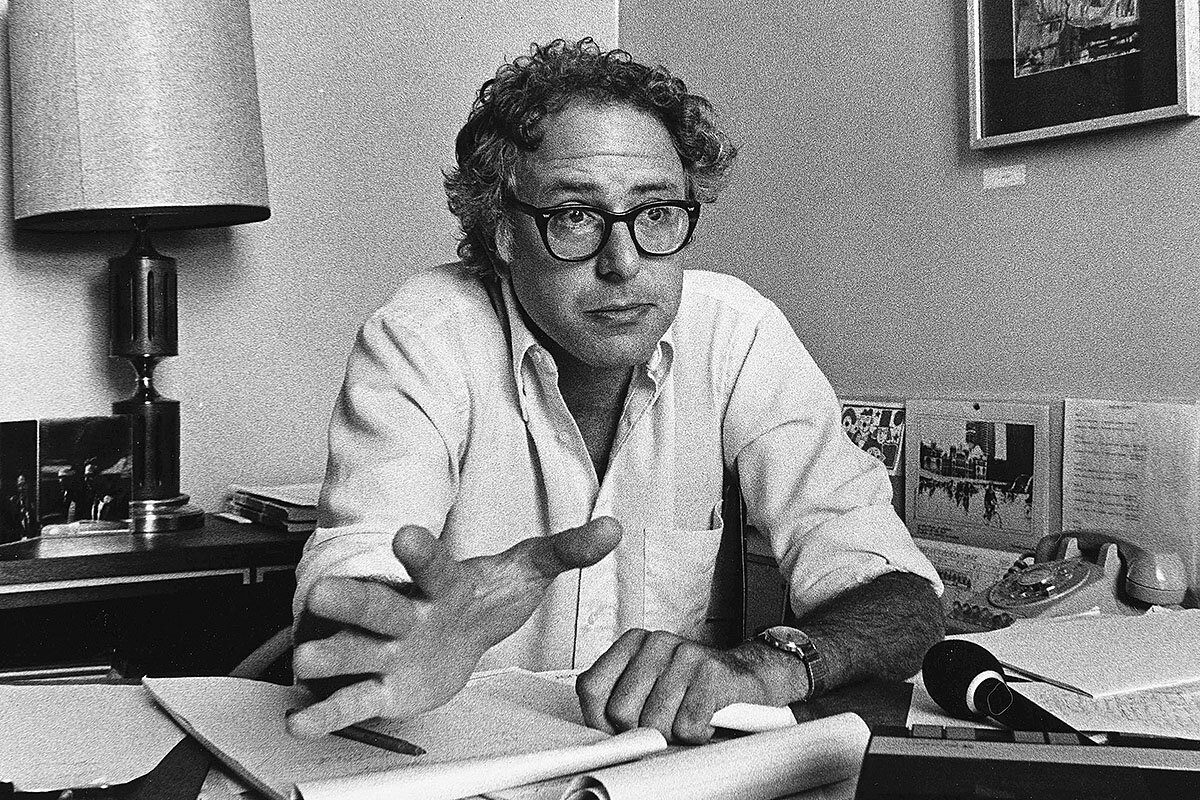

Now on to our five stories of the day, which include a deep dive into the lessons of Bernie Sanders’ years as mayor of Burlington, Vermont, and a look at how indigenous people in Canada are flipping expectations and planning to benefit from resource extraction.