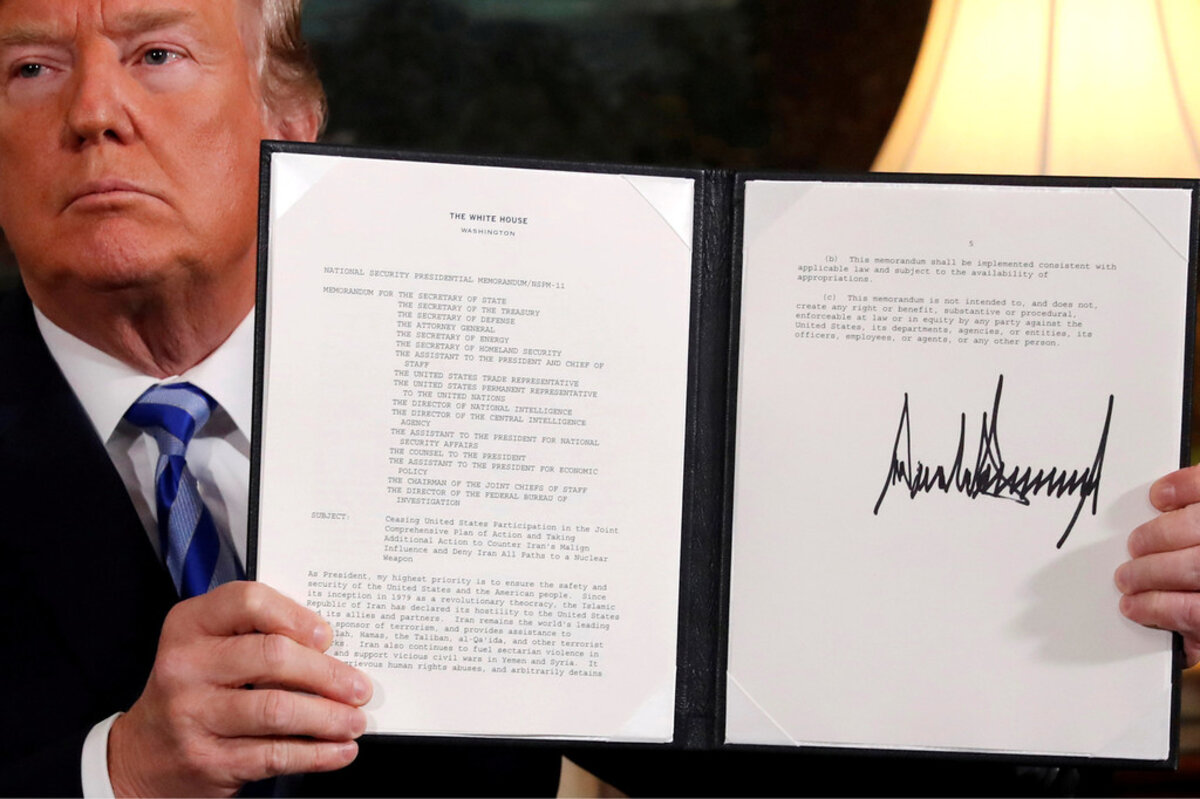

The juxtaposition of withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and an impending summit with North Korea over its nuclear weapons program help us understand key drivers of President Trump's approach to international dealmaking: a preference for face-to-face talks and a stomach for brinkmanship.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

The glitz and glam of an event like Monday’s Met Gala in New York, known as “fashion’s biggest night out,” are hard to ignore, even for a fashion know-nothing like me. But what really turned my head was a recent announcement by one of its hosts. As Donatella Versace told 1843 magazine: “Fur? I am out of that. I don’t want to kill animals to make fashion. It doesn’t feel right.”

Other designers share the sentiment. Gucci, for example, maker of the fur-lined loafer, announced late last year that its 2018 spring line would be fur-free for the first time.

Many consumers had already reached that conclusion, of course; pressure has been growing on the fur industry for years. Millennials are tipping the scales with their market clout and interest in ethical consumption. Consumers can easily track which brands measure up to their ethical standards. Technology is helping propel the shift, with new forms of faux fur getting the ultimate seal of approval from designers such as Stella McCartney and vegan leather rising in prominence.

When ground-level momentum and high-end sensibilities, ethics and good business, meet, it feels as though it’s a tipping point. As Gucci’s CEO put it, fur now feels “a little bit outdated.”

Now to our five stories, starting with insights on a likely summit between US President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. The breakthrough today: the release of three US citizens imprisoned in North Korea.