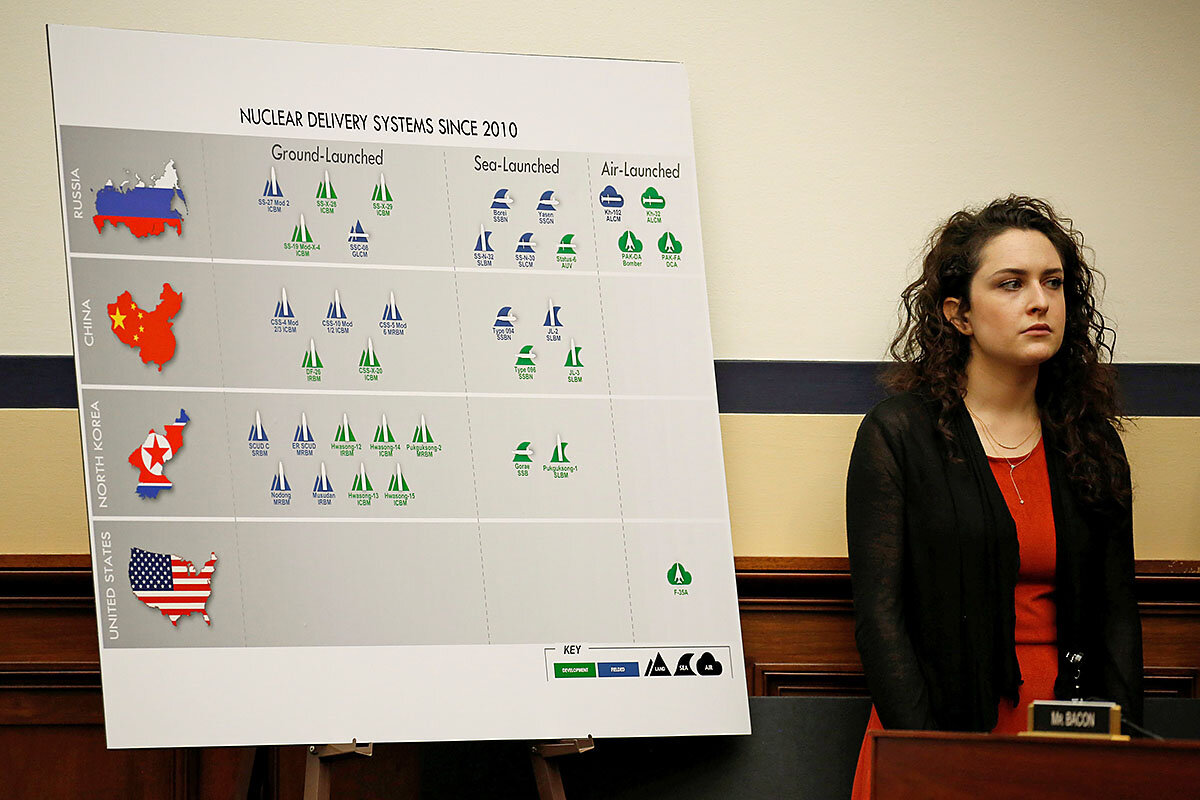

In the United States, it's the memo that few people are paying attention to. But in Russia, the new nuclear posture review is raising more than a few alarms. Russians see it as the US opening the door to the use of nuclear weapons outside the bounds of mutual assured destruction – a shift in decades of philosophy that makes US-Russia relations more uncertain.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

In Pyeongchang, the last-minute crunch is on before the Olympic caldron is lit. Athletes from returning veteran Lindsey Vonn to Colombia’s first speedskater, Laura Gomez – who had never been on ice before July and arrived in South Korea without gloves – are preparing for Friday’s opening ceremonies.

Staff writer Christa Case Bryant, once a nationally ranked cross-country skier herself, will be covering the Games for us. Christa, also our former Jerusalem bureau chief, shared her thoughts after a trip to the DMZ:

“The most surprising thing about the demilitarized zone is not the barbed wire or the loudspeakers that can blast propaganda for 15 miles or the military observatories perched on opposing hilltops,” she says. “It’s the surf.

“There are things about conflict zones that no one bothers to mention, like the spring wildflowers that carpet the West Bank or the deep turquoise waves that pound away at the Korean Peninsula,” Christa adds. “The natural beauty does not, of course, ease the political tensions. Those tensions run deep, and not even an Olympic gesture of goodwill can ease them in any lasting way.

“But amid persistent conflict,” says Christa, “perhaps there is a promise in these wildflowers and waves that there is more to any place than war and rumors of war.” She'll look at those currents in a story tomorrow, when the two Koreas march into the opening ceremonies as one team.

Now, here are our stories of the day, looking at transitions, a quest for equality, and a new appreciation of art.