Would taxing robots help the people whose jobs they'll take?

Loading...

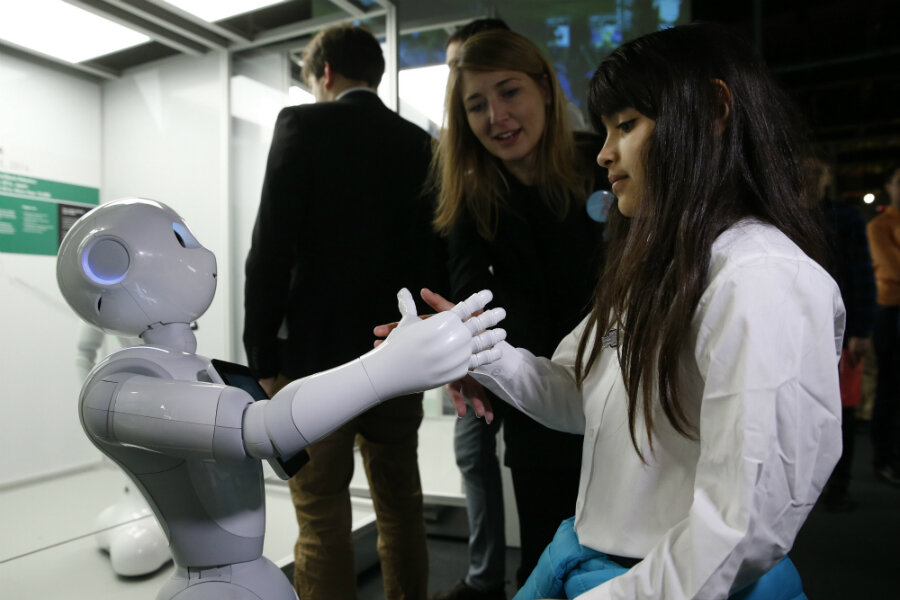

Automation may soon affect even industries and jobs we thought were immune, so what should countries do to prepare for those left jobless and behind? Bill Gates recently offered a simple solution: Tax the use of robots. He argues that such a tax would both “temporarily slow down the spread of automation” and fund social safety net programs for those who lose their jobs to technology.

Gates is not the only one to suggest the idea. French presidential candidate Benoit Hamon of the Socialist Party recently proposed a universal basic income partially funded by a robot tax. The European parliament also just voted down a proposal to fund support for workers who lost their jobs due to “robotics and AI” through a robot tax.

While it is of vital public policy interest to support technology-displaced workers, the premise of a tax on the use of robots raises several thorny issues. One is the difficulty of specifying which kinds of robotic automation should be taxed, and more generally, what counts as a robot.

What distinguishes a machine we now accept as integral to economic productivity from a robot whose activity we would wish to tax? Washing machines, for example, certainly put many launderers out of work, but they also helped make it possible for millions of women to join the paid workforce. A robot tax, as Gates proposed, may end up being a tax on innovation and would force Congress and the IRS to make the perhaps impossible distinction between labor-saving machines and labor-enhancing ones.

Taxing robots would also fundamentally change the way the United States currently taxes business investment. Instead of treating equipment as a depreciating asset for which a firm takes a deduction in computing its taxable income, Gates would single out a subset of these investments for a new tax.

There is also debate among economists over whether robots and automation significantly impacts employment. While a report by researchers at Oxford University estimated 54 percent of jobs in the EU are at risk of “computerization,” another report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development last year estimated only 9 percent of jobs in 21 OECD countries are automatable.

And although automation certainly has it losers – the American steel industry lost 75 percent of its work force between 1962 and 2005 – the creation of new types of jobs and industries may mean that overall employment is not significantly affected. A recent paper from Georg Graetz of Uppsala University found that industrial robots had no significant effect on overall employment, meaning the total number of hours worked by people in a country stayed around the same even when the use of those devices increased.

For those left permanently behind by the technological revolution, these facts will understandably be of little comfort. Taxing robots and other technical advances, however, will not make the human consequences of automation and robotics go away.

This story originally appeared on TaxVox.