What do tariffs mean for carmaking and US communities? Clues from one Georgia town.

Loading...

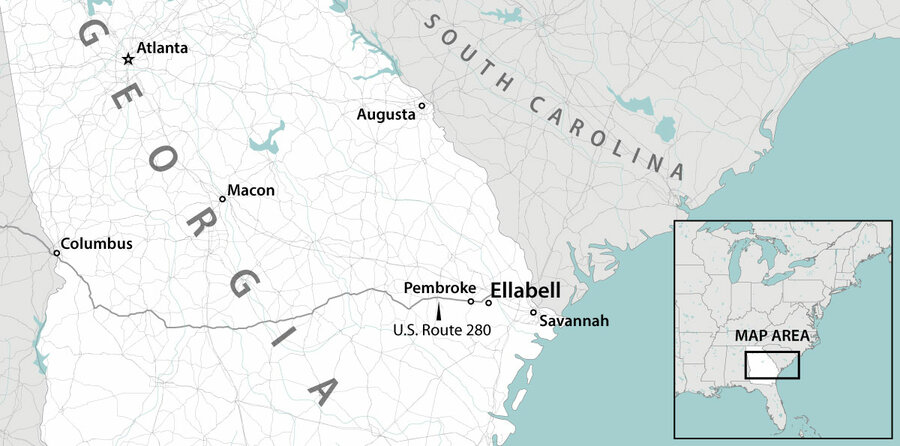

| Pembroke, Ga.

President Donald Trump’s tariff plan appears focused around a simple tenet for any manufacturer: Produce in the United States if you want unfettered access to U.S. markets. If that’s the demand of this moment, Hyundai Motor Group of South Korea looks in some ways like a brilliant strategist.

Back in 2022, months before then-President Joe Biden approved credits for buying electric vehicles, and long before the sharp rise in tariffs that President Trump has announced recently, Hyundai signed the biggest economic development deal in Georgia’s history.

This new $7.6 billion EV factory broke ground just over two years ago in a massive pine grove just west of Savannah, Georgia.

Why We Wrote This

South Korea’s Hyundai is investing big near Savannah, Georgia. It’s bringing auto jobs, but it’s not a panacea for the effects of tariffs, and residents see costs as well as benefits for their community.

Last week, nearly 2,000 American Hyundai employees started churning out vehicles, aided by a horde of robots directed by dozens of South Korean nationals now working for Hyundai in the U.S.

Then last month, as the Trump administration readied tariffs on foreign-sourced materials, the carmaker announced it was building a new steel mill in Louisiana.

“Maybe [Hyundai’s leaders] are very prescient and can think that far ahead,” says Trey Hood, a political science professor and an expert on Southern politics at the University of Georgia in Athens. “But the fact is, they are very well positioned, by accident or whatever.”

But if the company is becoming better positioned for U.S. production, the story of its Ellabell, Georgia, plant also reveals how hard it is for any manufacturer to truly win from the current landscape of high and uncertain tariffs.

Among the challenges: The tariffs will still affect Hyundai, like other auto companies producing in the U.S., to the degree that parts are imported. What’s more, the new Georgia plant was supposed to produce only electric vehicles. But as the Trump administration is moving away from special support for EVs, Hyundai recently announced the factory will also build hybrid vehicles.

A larger question hangs over the community here: How beneficial will a factory like this one be for local life and livelihoods?

The auto industry is exceptionally complex and capital-intensive. The new Hyundai Metaplant here raised its curtain late last month on a rearranged stage. The arrival of heavy tariffs is accompanied by a sharp slump in stock markets. Carmaker Stellantis announced temporary layoffs and factory downtime affecting U.S., Canadian, and Mexican plants – a sign of how tariffs may destabilize both supply chains and consumer demand.

Charging ahead

But Hyundai, which saw record sales in March, is charging ahead. President Biden and President Trump have both hyped their roles in Hyundai’s total $21 billion U.S. investment.

The massive plant, located in Ellabell, about 25 miles outside Savannah, may eventually employ as many as 8,000 people. It is already changing the demography and economy of the area of Georgia known as the Coastal Empire – the barrier islands, marshes, and swampy lowlands of southeast Georgia that support a thriving coastal economy.

Presidents and cars

Mr. Trump isn’t the first president to focus on the auto industry’s outsize role in the $29 trillion U.S. economy. President Ronald Reagan negotiated import limits on foreign-built cars, temporarily raising consumer costs. Two major U.S. automakers were bailed out under President Barack Obama during the Great Recession. President Biden also signed the Inflation Reduction Act, which featured $7,500 tax rebates on electric cars.

Now comes President Trump’s dramatic move this past week, erecting what amounts to a nearly $1 trillion tariff wall. But that wall creates economic and political risk alongside its incentives for manufacturers to build more American factories.

As a result of the tariffs, Fitch Ratings just downgraded its U.S. car sales forecast. In anticipation of the tariffs – which include a base of 10% for all goods and 25% on imported cars – consumer sentiment continued a steep drop in March, reaching its lowest levels since November 2022, according to research by the University of Michigan.

Against that backdrop, the White House is asking Americans to trust that short-term price pain and potential domestic layoffs will yield a new “golden age” of higher wages, more jobs, and revived communities.

Testing tariff support, changing factory towns

“Tariffs have redistributional effects,” says Robert Johnson, an international economist who teaches at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “But who are the winners and losers?” he asks.

“I’m not sure what the administration is going to learn when they do this and people go out and pay $7,000 more to buy a car,” says Professor Johnson, a trade policy expert. “That’s going to test the depths of anti-trade support.”

Edmond Foss, a retired truck driver living near the Hyundai factory, voted for Mr. Trump. But he worries that the president’s sweeping gestures – not just on trade – are more show than substance. “Here’s a guy who wants to put an American flag on Mars. I mean, what’s the point?”

He says those concerns may be echoing in other places across the U.S. Mr. Foss has already seen the impact here in Pembroke, a sleepy railroad town just a few miles down U.S. Route 280 from the new car plant.

“Not everyone is behind it,” he says. “Traffic is growing. Houses are going up everywhere. It feels overwhelming.”

Bobby Kaskela, a local carpenter, agrees that “There’s no doubt we’re going to see some dramatic changes.” But to his way of thinking, Pembroke will ultimately benefit from a renewed focus on domestic manufacturing, even if it raises prices.

Behind the scenes, the city has quietly been preparing for the opening of the Hyundai factory, increasing the housing stock and the capacity of the town’s wastewater treatment plant. In the past, a standard subdivision held about 30 homes. In recent months, Pembroke officials have heard developers pitch new subdivisions with 360 homes each.

“If you don’t revise, you’ll die; if you don’t adapt, you’ll be left behind,” says Chris Benson, the city administrator guiding Pembroke’s preparations. “I would love to have a parking problem in downtown Pembroke, which we currently don’t have. At the same time, when people see something they’ve never seen before, it generates a lot of fear and concern.”

Manufacturing vision or just great timing?

But it is unclear whether the boom here in Pembroke will represent President Trump’s vision coming to fruition.

“I think places like Pembroke will be managing growth rather than decline, and that’s a much better problem to have to deal with overall,” says Professor Hood, the director of the Survey Research Center at UGA. “But whether we’re going to bring back the heyday of American manufacturing – sort of 1950s post-World War II – I’m dubious that’s going to happen. The administration can try to control the market, but [the market] still has a huge sway over itself.”

Republican Rep. Earl “Buddy” Carter, who grew up along the Savannah River, points out that Americans import vastly more cars from the European Union than the EU imports from the U.S.

To his way of thinking, unfair trade deals “have been going on for a long time and, like any situation like this, the longer you let it fester, the harder it is to address,” said Representative Carter in an interview with the Monitor. Mr. Carter represents Georgia’s 1st District, including the metro Savannah area. “And President Trump is finally addressing it,” he added. “And, yes, addressing that is probably going to cause short-term pain. But long-term is what he’s thinking about.”

Higher salaries, good food, and family values

At last week’s plant opening, several workers gave speeches pointing to the new jobs that this new plant will provide to this area of rural Georgia. Hyundai’s wages run to almost $60,000 yearly, compared with the $42,000 per capita income surrounding Bryan County. Managers play up cultural similarities to promote camaraderie on the shop floor. Hyundai has repeatedly credited the quality of the U.S. workforce in Southern states as a reason for their investments.

At the grand opening, Hyundai Motor Group CEO José Muñoz credited relationships, not politics, for his company’s decision to bet large on the U.S.

“America has become, by far, the largest market for the group,” he told reporters. “We invested because we saw the opportunity, not because of who was president or what incentives were on the table.”

Chris Winfreed, a lifelong Pembroke resident, is graduating from high school in May and has enlisted in the Air Force for a commission of at least three years. He says that, for now, he is not considering possible opportunities at Hyundai for when he returns. To him, all the talk of tariffs and jobs can overshadow what he considers key community virtues – like natural beauty and simple, small-town life.

“They’re building houses and restaurants, but they haven’t even fixed the roads yet,” he says. “Do I think Pembroke will get bigger? Yes, I do. Will it get better? That, I am not so sure about.’’