Inflation’s lasting pressure: A hotel worker’s story shows the struggle

Loading...

| Boston

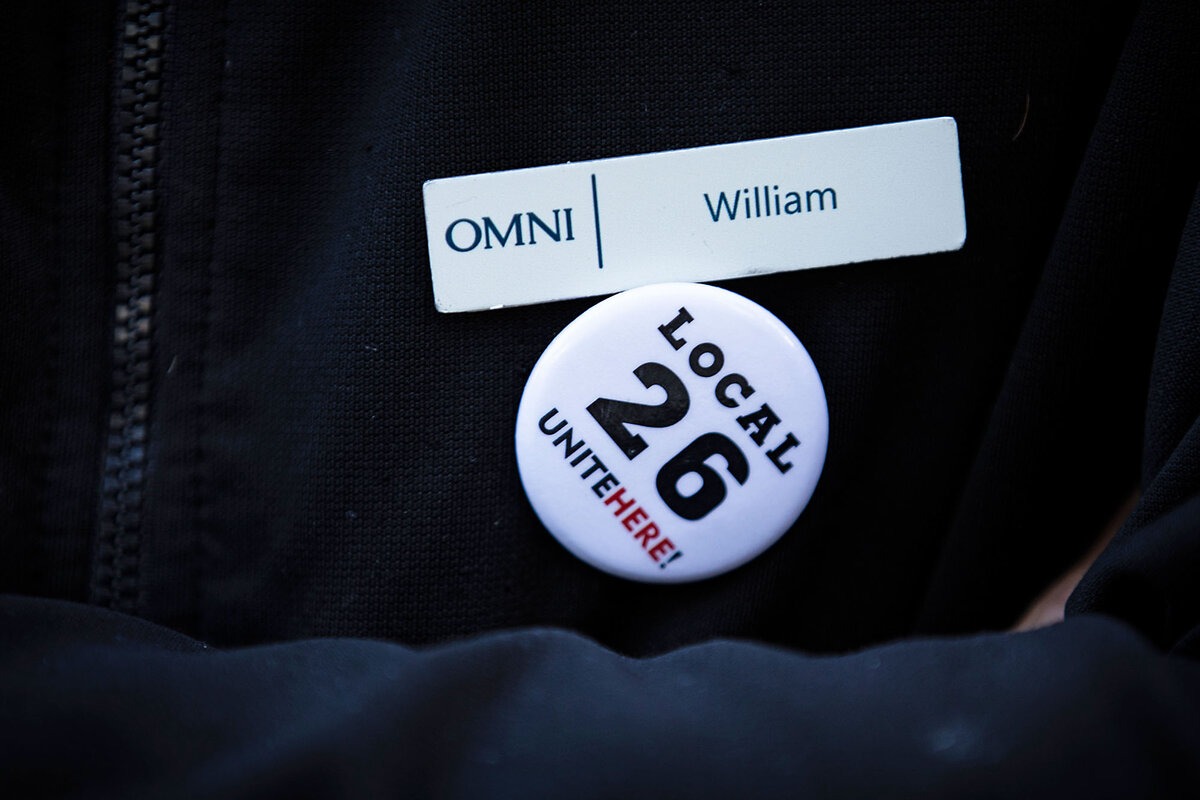

In the summer of 2023, William Brown was taking on credit card debt as the cost of his rent and groceries jagged up. His goals to buy a home and start a business were slipping out of reach.

The 25-year-old earned around $28 an hour as a night houseman on the evening shift at Omni Boston Hotel at the Seaport. The inflation rate was falling, but he, like many Americans, was paying for a year of price spikes.

He decided he needed a second job and took one at another high-end hotel. Working two eight-hour shifts each day, he had 30 minutes to speed on his moped from one to the next. He was only at home to sleep, and only slept four hours each night. He lost 20 pounds and felt “loopy” and “robotic” from sleep deprivation, he says.

Why We Wrote This

Inflation has come way down in the past two years. But the issue might have decided the recent presidential election, and its effects still weigh on many Americans.

The mother of his 3-year-old daughter told him he was making things harder for her, he says. “Well, that’s not what I’m trying to do,” he thought at the time.

He was trying to ease the burden of inflation on his family. Prices rose quickly in 2021, with the inflation rate peaking at 9.1% in June 2022 and stabilizing at around 3% by the following summer. But even with the falling rate, prices now are around 20% greater than in 2021.

People like Mr. Brown are still feeling the aftershocks. Inflation can have long-term consequences, particularly for lower-income people, according to a study by Stefanie Stantcheva, a professor of political economy at Harvard University.

It can force people to put off essential expenditures – like paying bills or going to the doctor. It can also provoke a sense of inequity, she says, as people become aware that not everyone feels inflation to the same degree.

And in November, exit polling indicates high inflation was a key reason many people voted for Donald Trump over Kamala Harris for president.

Though the rise in prices has slowed, and wage growth has since caught up, a sense of urgency remains for millions of Americans. Just last week, with inflation still higher than its 2% goal, the Federal Reserve paused interest-rate cuts and noted uncertainties that now include new import tariffs imposed by President Trump.

Mr. Brown’s story illuminates how the powerful economic force continues to shape people’s lives and attitudes.

“People view inflation as something that is totally out of their control ... and something that is imposed on them,” says Nathan Wilmers, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management, interpreting Dr. Stantcheva’s work.

Mr. Brown’s problems are not solved. But after navigating a mental health crisis triggered by the two jobs, he rocketed into a leadership role in his union, which has secured a pay raise that could help.

“You’re working just to live, so you’re not going anywhere forward”

Mr. Brown got his job at Omni in the spring of 2022, just before the inflation rate peaked. The war in Ukraine had driven up energy prices, federal subsidies superheated demand, and the pandemic disrupted supply chains. The Federal Reserve raised interest rates with the goal of bringing down the inflation rate, but some economists say the moves could have come earlier.

At the Omni, Mr. Brown hauled garbage gathered from rooms in each hallway of the massive hotel. “I basically walk, like, 40 floors a day, just grabbing the trash, up and down,” he says.

At first, the money felt substantial: He could buy food for himself and his daughter, who splits her time between him and her mother, he says; save some money; pay rent in the four-bedroom house in Dorchester he shares with his mother, two of his brothers, and his sister; and help his siblings with their cellphone bills.

But by summer 2023, the growing cost of living, especially in an urban center like Boston, had eaten into his paycheck, he says. Boston is the fifth-most-expensive U.S. city, and it costs $60.08 per hour to live there comfortably, a March survey by SmartAsset found.

Mr. Brown’s rent had gone up by hundreds of dollars, he says. That was a common story across the United States: Housing affordability for renters was its worst yet in 2023, with the number of cost-burdened renter households hitting an all-time high, according to Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Mr. Brown couldn’t even afford to take his daughter, a gregarious preschooler who loved fish, to the aquarium.

He dreamed of starting a business power-washing houses and raking leaves with his brothers, but didn’t have money to put toward it.

With the one check, he says, “You’re working just to live, so you’re not going anywhere forward.” His co-workers can’t afford to go out with their families or go on vacations, he added.

So, as many of his co-workers did, Mr. Brown got a second job – this one at another luxury hotel called Raffles Boston, where he would earn around $26 an hour on top of the $28 at his first job.

But after around a month working 16 hours a day on little sleep, he realized his mental and physical health were declining. He went back to the one job. Later, while he was on medical emergency leave, a doctor helped him realize he was also coping with a traumatic experience. A few years ago, he says, the police came to his house to arrest one of his brothers. He saw them shoot both of his dogs. One of them died.

“I took pride in my job, honestly”

In July 2023, when Mr. Brown had just started the two-job arrangement, something happened that shifted his attitude toward Omni and his union, Unite Here Local 26.

Mr. Brown says he requested a schedule change for his evening shift at Omni. The 30 minutes between shifts was not enough time to get from Raffles to Omni, he says. And his work is easier during the later hours, when elevators and halls are not crammed with guests dragging suitcases on their way to check out.

When the request was rejected, he says, he felt disrespected.

“When I came here, I was one of the people that would, like, clean the baseboards, and I took pride in my section and I took pride in my job, honestly,” he says. “I was like, ‘This is a brand new hotel. We’re at four-point-something. We’re trying to get to five stars.’”

He went to the union, learned his rights under the union contract, and began to stand up for colleagues he says were mistreated. Less than six months later, his co-workers elected him as a shop steward, and he now represents about 300 of them.

His job is to advocate for his colleagues’ rights under their contract.

“I deal with really frustrated people, emotional people,” he says. “It’s emotional for me because when I see someone that’s sad or feels like they’re about to lose their job, it makes me go harder for them because it makes me sad.”

In September 2024, Mr. Brown helped lead a strike, joining more than 10,000 hotel workers across nine cities, according to Unite Here. Hotel management didn’t respond to a request for comment about what led Mr. Brown to consult the union, or about the strike and its resolution.

Since starting as shop steward about a year ago, he says he and his co-workers went from “saying, like, ‘The union’s the Mafia; the union doesn’t really exist here,’ to us realizing we are the union.”

Unite Here’s new contract with Omni includes a $10 per hour raise for nontipped workers over the next four years. Mr. Brown says it can’t come soon enough.