A robotaxi, a collision, and the bumpy road to an AI future

Loading...

| San Francisco

While artificial intelligence promises to transform society in major ways, driverless taxis offer a stark example of the bumpy road the technology faces before it reaches its potential.

In California, for example, a serious collision involving a robotaxi is forcing the state to reevaluate its growing push into driverless technology.

Last week, the California Department of Motor Vehicles suspended the right of Cruise to operate driverless taxis in the state after one of its San Francisco robotaxis hit and dragged a woman some 20 feet on Oct. 2. The state agency accuses the company, a unit of General Motors, of failing to disclose that dragging incident – a charge the company denies. Cruise has since paused all its driverless operations in the United States, it announced, in order to “examine our processes, systems, and tools and reflect on how we can better operate in a way that will earn public trust.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onA recent collision in San Francisco was initiated by humans but also brought safety hurdles for driverless cars into sharp relief. It highlights the role regulators will play in the issue of new technology and public trust.

The irony is that everyone agrees that people triggered the incident, not the robotaxi. But that fact may not be enough to save the company – and perhaps the driverless taxi industry as a whole – from serious reputational harm. It is the latest example of how regulation of young technologies can shape emerging industries and public perceptions in unexpected ways, and gaps in that regulation can prove as hazardous as the technology itself.

It’s a particularly timely lesson as various forms of AI begin to course through the economy and society.

“This is early days, and it is the Wild West of policy, particularly at the state level,” says Billy Riggs, a University of San Francisco professor who studies transportation innovation. “There’s a perception that somehow the technology isn’t ready. And I would say many times perception can become reality.”

Increasingly ubiquitous in San Francisco

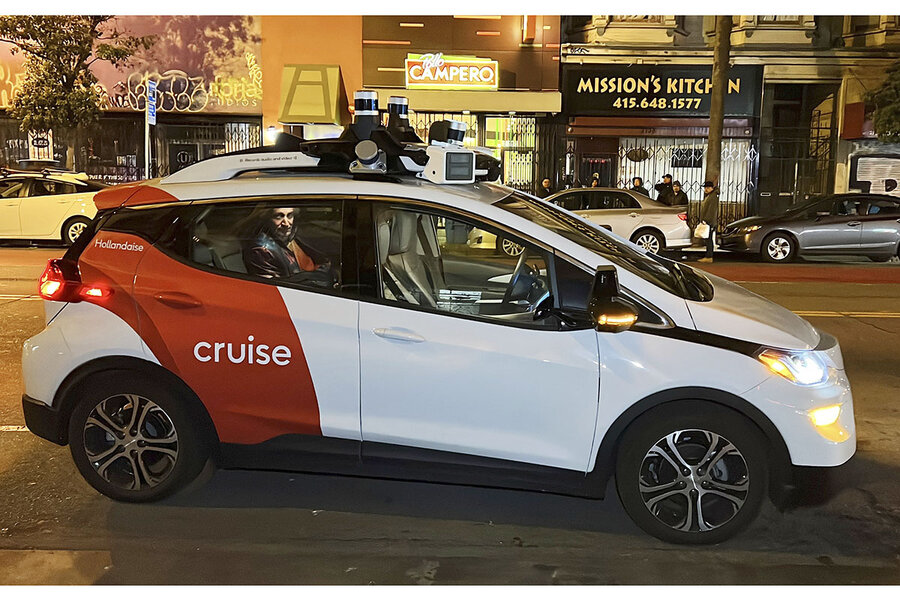

For months now, San Franciscans have become increasingly familiar with the sight of cabs with rooftops brimming with sensors and laser radar moving about the city with no one at the wheel. Besides Cruise, Waymo (owned by Google parent Alphabet) and Zoox (an Amazon subsidiary) have deployed the technology here, although Zoox still has operators in the driver’s seat, just in case.

While the public can now use robotaxis in a growing number of cities, such as Austin and Phoenix, San Francisco’s dense population, narrow streets, and hills pose some of the toughest challenges for the technology. The reaction has been mixed.

“We love Cruise!” says Alyssa Guevara, a junior at the University of San Francisco. During her first trip in January, when driverless cabs were still in the testing phase and rides were free, her robotaxi started to pull around a double-parked car into the opposite lane and stopped. Then a firetruck came toward her, unable to proceed. She and her friend used the car’s internal communication to reach an operator. Within five minutes a Cruise employee entered the car and moved it.

“I wasn’t worried,” says Ms. Guevara. “I honestly felt really safe in a weird way.” Since then she has taken more Cruise rides than she can count, although none since the company started charging for service in August.

A threat to human jobs?

San Francisco cab drivers, by contrast, are wary. New technology, in the form of ride-sharing apps from Lyft and Uber, blindsided their industry nearly a decade ago. And because Lyft and then Uber were able to use their technology to turn anyone into a cab driver without the costs of training or taxi medallions – a regulatory gray area – employment in the taxi industry plummeted.

“When Uber and Lyft came in, it basically meant that an amateur could do a professional’s job,” says Mark Gruberg, co-manager of Green Cab LLC. At its peak in the early 2010s, the tiny driver-owned company had 19 taxis; it now has eight. Many cab drivers, who bought a taxi medallion (a city-issued license) for up to $250,000 before Uber and Lyft took off, have quit, sitting on mountains of debt with medallions that are nearly worthless. Longtime San Francisco cabbie Matthew Sutter still owes $150,000 on his. Mr. Gruberg expects more drivers to retire if the new wave of AI floods in as driverless cabs.

“They don’t wait in taxi lines; they don’t take a break; they don’t stop; they don’t have to go to the bathroom,” says Evelyn Engel, a cab driver and executive board member of the San Francisco Taxi Workers Alliance. “And if they’re not with a passenger, they’ll keep driving because they’ll be mapping and updating software and so forth. ... The Utopian vision is that everybody will take a self-driving car. We can get rid of parking lots at Safeway and parking lots downtown. But the flip side of that is that there won’t just be a rush hour; there’ll be cars constantly on the road, circling the block if nothing else.”

Still, the regulation that didn’t protect local cabbies from the rise of Uber and Lyft may still offer them some protection. Many of the nearly worthless medallions still allow traditional taxis to pick up passengers from the airport, which Uber, Lyft, Waymo, and Cruise cannot do. Ditto for transportation for people with disabilities, a franchise the city pays only taxi drivers to provide.

Instead, it appears the gig workers at Uber and Lyft – those with the least regulatory protection – are most at risk from the technology.

“I hate it,” says one San Francisco Uber driver, who declined to give her name. “The reason I hate them [the driverless cabs] is that they are taking away jobs in the future.” She drives up to 40 hours a week. It is her only employment.

The technology has also irritated a growing number of San Francisco drivers and city workers who have had to deal with a series of problems and delays caused by the robotaxis. The public backlash began in August in the city’s North Beach neighborhood, a day after the California Public Utilities Commission allowed Cruise and Waymo to move from a limited test phase to round-the-clock operation and charging for rides.

Publicized problems

“It happened right there,” says Aaron Peskin, president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, pointing to the intersection of Vallejo and Grant streets from his chair outside Caffe Trieste. Ten Cruise taxis inexplicably came to a halt here on Aug. 12, blocking all traffic on both one-way streets and causing a massive traffic jam. Heavy cellphone use during a local musical festival limited the available wireless bandwidth, Cruise says, delaying the company’s remote operators to move the cars out of the way.

Four days later, a Cruise cab plowed through traffic cones and drove into freshly poured concrete. That same month, a Waymo vehicle came to a stop between a fire engine and a car on fire. That forced firefighters to carry their hose around the taxi to fight the blaze.

The fire department alone has logged dozens of incidents in which the driverless cars have interfered with emergency personnel, including running over fire hoses and blocking fire trucks and other emergency vehicles, according to Deputy Fire Chief Darius Luttropp. The city’s fire chief says driverless cabs are not ready for prime time.

The companies point out that such incidents are rare exceptions. In San Francisco and Phoenix, where Waymo is also active, “the Waymo Driver encounters active emergency vehicles approximately once per 100 miles, which equates to over a 100 encounters per day,” the company said in an email. “The vast majority of these often challenging and complex encounters have been without issue.”

Cruise, with the most robotaxis in San Francisco, has come in for the lion’s share of the criticism. After two nonfatal car crashes in mid-August, one involving a fire truck in emergency mode that hit a Cruise cab, the state DMV stepped in. Cruise agreed to halve the number of cabs operating in San Francisco while the department investigated. Now, the department has suspended indefinitely the company’s driverless cars from the state, although Cruise can still test its cars if there’s a safety driver.

This month’s dragging incident represents the biggest challenge yet for Cruise, which has been harboring plans to expand to many other cities.

After the Oct. 2 collision, the company initially was eager to share its video of the incident with reporters, says Brad Templeton, chairman emeritus of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and a self-driving car consultant. He asked for and received the video, which showed a woman crossing an intersection against the light, and then getting hit by a human driver and deflected into the path of Cruise’s robotaxi. The driverless car began braking but couldn’t avoid hitting the woman.

What the partial video did not show was what happened after the collision. The car came to a stop and then moved slowly to the curb, as it was programmed to do, dragging the woman with it. This incident poses two challenging questions for the company: (1) Did it cover up the incident? (2) Are its cars really safer than human drivers, as it claims?

The company claims it was fully open about the incident with regulators. Cruise’s immediate focus was to prove its car did not trigger the incident and to help police track down the driver who did. (He or she fled the scene). So it shared the video that was immediately available, which only showed the events up to the initial collision, not the dragging incident later.

Cruise says it quickly alerted federal and state regulators, requested a meeting the following day, showed the full video, and answered questions. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration confirms it got the full video the following day. The state DMV says it did not. In its order last week suspending Cruise’s right to operate driverless taxis in California, the department cited state regulations allowing its actions if the manufacturer “has misrepresented any information related to safety of the autonomous technology of its vehicles.”

What future for robotaxis?

Unlike certain forms of AI, such as ChatGPT, that try to mimic humans’ common sense, driverless taxis strictly follow a set of rules based upon millions of miles of driving experience. For example, when the robotaxi dragged the pedestrian to the curb, its protocol apparently contained no exception for people caught under the car.

Cruise will be back on the streets of San Francisco, predicts Mr. Sutter, the taxi driver. “There’s so much money invested that they won’t just give up on this,” he says. But “in the end of it all, it’s not going to work. I really think there’s just going to be too much liability involved.”

Statistically speaking, robotaxis may ultimately prove to be safer than human drivers. They don’t speed, or get sleepy or inebriated. And the incidents that do occur, as regrettable as they are, allow the companies to tweak the software so the cars quickly become safer fleetwide.

“These vehicles are never going to be perfect,” says Mr. Templeton, the consultant. “The question that we’ll want to know is: Will the public feel that the serious accidents, which will happen, are a black eye for the whole industry? Or is there something where you say, that’s terrible, but at least it’s happening less often than it is with all the people who are driving?”