Inside a hotspot: Voices from the floor of a meat-packing plant

Loading...

Even before Iowa started shutting down due to the current pandemic, Khalil El-Amin’s employer gave him a special letter. It explained that he was an essential worker, in case the state went into lockdown and he got pulled over on the way to work.

He still has it in his glove box, even though he’s no longer commuting to his job at Tyson Fresh Meats in Waterloo, Iowa.

No one is.

Why We Wrote This

The meat industry has been hit hard by the coronavirus. Workers know how essential their jobs are, but some at one Iowa plant say the feeling is that they seem expendable. That could be changing.

On April 22, Tyson suspended operations in Waterloo, its largest pork-processing plant in the country, saying that protecting their 2,800 employees was its top priority. The move came amid intensifying pressure from local elected officials, increasing reports of positive COVID-19 cases at the plant, and hundreds of workers not showing up for their shifts amid rising health concerns.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The situation illustrates the dilemmas facing meat-packing plants, an essential part of America’s food supply chain. The pressures to stay open are immense, but public health officials say staying open can risk the well-being of those who keep them humming. More broadly, some workers say they have long felt overlooked and undervalued.

“I understand that we are vital to putting the food out there for not just America but the whole world,” says another Tyson worker who has tested positive for COVID-19 and agreed to speak on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution. “But if we are so vital to doing that, why not take care of us?”

Tyson’s Waterloo operation is one of about 20 slaughterhouses and meat-processing plants industry-wide that have shut down across the country as nearly 5,000 employees have been diagnosed with the disease. Last week’s pork production was down about 40% compared to the same period last year. For now, frozen and refrigerated meat is helping to fill the gap. Meanwhile hog farmers are facing the heart-wrenching prospect of mass euthanization.

In a bid to keep the meat supply chain running, President Donald Trump last week invoked the 1950 Defense Production Act in an executive order urging meat processing plants to run at the maximum extent possible – a move that experts say is designed to give the plants legal cover if employees fall ill.

The disruption is bringing to light a broad range of concerns about the U.S. meat supply chain, from a lack of flexibility and agility to the treatment of not only animals but also the people who work long hours to bring meat to American tables.

“I think there’s this tension of providing food … and then making sure that the people are safe,” says Rev. Belinda Creighton-Smith, a Baptist pastor and social justice leader in Waterloo, who says more than a dozen plant employees have come to her with their concerns. “We need to make sure that we’re taking care of our brothers and sisters first and foremost and not being concerned that we’re cutting into our profits and production slowing down.”

How the pressure built on Tyson

A third Tyson employee, whose name is being withheld for his protection, inspects gutted hogs and takes pride in the company’s high standards for its meat. One day in April, he says, he overheard supervisors at work discussing positive cases at the plant.

The next two days, he called in to say he wouldn’t be coming to work. Both times, he says, human resources told him he was more likely to get COVID-19 shopping at Walmart than coming to work, where he would be safe.

He came back on the third day, only to find out that someone he worked near that day fell ill after work. “I needed the money,” he says, but worried about endangering his baby son and his girlfriend. “It almost seemed like, man, we just was almost considered throwaways instead of essential workers.”

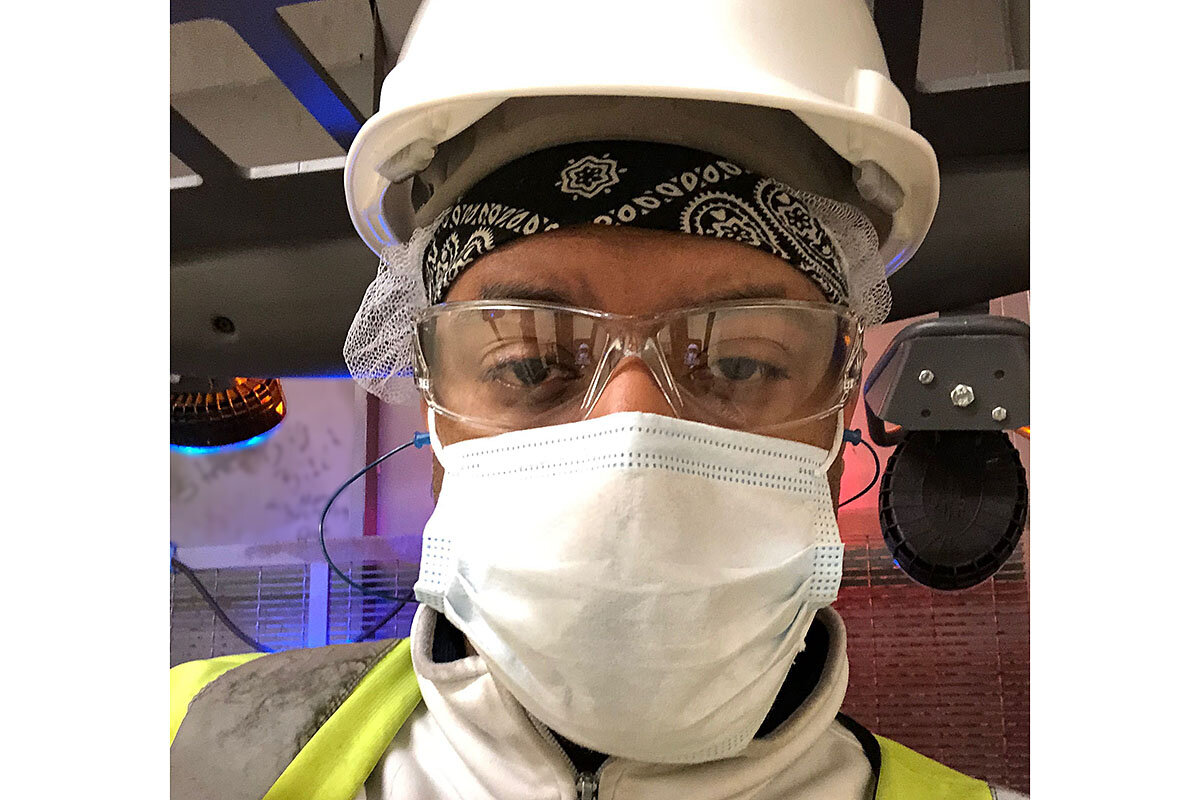

Mr. El-Amin, on the other hand, who works on the loading dock and has limited interaction with other employees during his shift, says he’s been impressed by the company’s proactive approach. They deployed workers to wipe down his forklift every other hour, he says, put up signs in the hallways, installed temperature scanners for arriving employees, and erected plexiglass barriers at the lunch tables. Before they were able to procure masks, they handed out cotton bandanas.

“I felt like, ‘Wow, they’re really trying to do something for us here,’ ” he says.

Many meat-packing workers come from minority backgrounds and other populations that have been disproportionately impacted by the current crisis. Tyson is one of the largest employers in Waterloo and employs a diverse workforce, including many foreign workers, some of whom have limited English skills and rely on company-provided interpreters.

While workers say the pay is good and it offers a rare opportunity for those without a college degree to advance into management positions, the company has come under fire for how it has handled the coronavirus crisis.

“The health and safety of our team members is our top priority, and we take this responsibility extremely seriously,” said Tyson spokeswoman Liz Croston in a statement to the Monitor. She said the plant has provided and enforced the use of PPE for its workers, checked them for symptoms, and carried out a deep clean and sanitization while the plant is idle. The company, which does not offer paid sick days, has also relaxed its attendance policy and eliminated waiting periods for short-term disability coverage, which now covers 90% of regular pay for those diagnosed with COVID-19.

“We are continuing to work closely [with] health officials to ensure our efforts meet or exceed local, state, and national guidelines,” she added.

One of those health officials is Sheriff Tony Thompson, who oversees the planning and operations for the local emergency center spearheading the response to COVID-19.

On April 10, he visited the Tyson plant with the county health department director and another colleague. He says he observed that only about a third of employees were wearing facial coverings and there was no apparent enforcement of PPE.

That day, Tyson knew that they had three positive cases of COVID-19, but public health officials knew the total case numbers among plant employees was in the teens, Sheriff Thompson adds. Yet the plant was being thoroughly cleaned only once per day, around 11:30 p.m. after three shifts of workers had been through.

As he left the plant, he recalls turning to his colleagues and saying, “They just drove a Mack truck through our defenses…. We’ve got to shut this down.”

Within a week, he and 19 other local officials – including six state representatives and seven mayors – signed a letter urging Tyson to voluntarily cease operations.

Democratic state Rep. Ras Smith, a signatory who lives two miles from the plant, said the hope was to avoid broader losses by all parties.

“It wasn’t about Tyson vs. them, or Waterloo vs. the pork producers,” he says. “If we act aggressively now,” the thinking went, “we can save ourselves heartache, cost, and lives in the future.”

The county currently has identified more than 1,500 cases and 18 deaths. The Iowa Department of Public Health on Tuesday declared outbreaks at five meat facilities in Iowa, and said that so far it has identified 444 cases from the Waterloo plant, with 17% of workers tested so far. Two workers from Tyson’s Columbus Junction plant have died.

At a press conference on Monday, Sheriff Thompson praised Tyson for “massive improvements” toward making their plant safe. A meeting Friday with Tyson representatives “was an energizing and encouraging first step forward to get that plant reopened.”

The people behind the bacon

Iowa is the top pork producer in America, and the shutdown of plants like the one in Waterloo has created a significant bottleneck. Iowa State University economist Dermot Hayes has described the pork supply chain as an escalator that can’t be turned off. If you put a gate at the top, the pigs pile up quickly, with nowhere to go. They gain weight so rapidly that even during a short plant closure they could become too big for a plant to accommodate when it reopens.

The USDA has confirmed $1.6 billion in support for pork producers. But it’s not just financial losses farmers are worried about.

Many are trying desperately to prevent their hogs from going to waste, from feeding them extra fiber to slow down their weight gain to selling live hogs to hunters who will use the meat for their family, says Iowa Pork Producers Association CEO Pat McGonegle.

“We are using every tool we have to find every avenue that is available,” he says, including using local butchers to process the meat for food banks across the state. “Not in my 30 years of doing the pig business have I seen anything like this.”

One thing the pandemic has revealed is the need for greater flexibility and agility in the meat supply chain, says Bobby Martens, a professor of supply chain management at Iowa State University’s business school. One of the early reasons for the bottlenecks was meat that had been packaged for restaurants rather than individual sale suddenly had nowhere to go when they shut down in March.

The worker safety issue is even more challenging. It’s easy to say in hindsight that Tyson should have shut down earlier, but they were balancing a lot of factors, including a potential customer backlash, he says.

“Tyson was between a rock and a hard place with some of the decisions they had to make, because consumers were not likely to understand why meat prices were so high, why pork wasn’t in the store, and at the same time [they] were balancing the health and well-being of their workers,” Professor Martens says.

As for the worker with a girlfriend and young child, he’s been quarantining since April 20. He has yet to see a paycheck, even though Tyson has said it would continue to pay employees. His rent is due by Thursday, and funds are running low.

The worker who has tested positive says he hopes Americans shopping in the supermarket are becoming more aware of the people who bring them the bacon, so to speak – from the farmers to the truck drivers to the processing plant workers.

“We’re behind the scenes until there’s a pandemic or something like this that comes along, and it’s put out there that, ‘Hey, this is what’s being done for you to go in there and pick it off the shelf and put it in your oven, or your skillet,’ ” he says. “Until this came along, I don’t think the average person even thought about what all is done for the meat to get out there to them.”