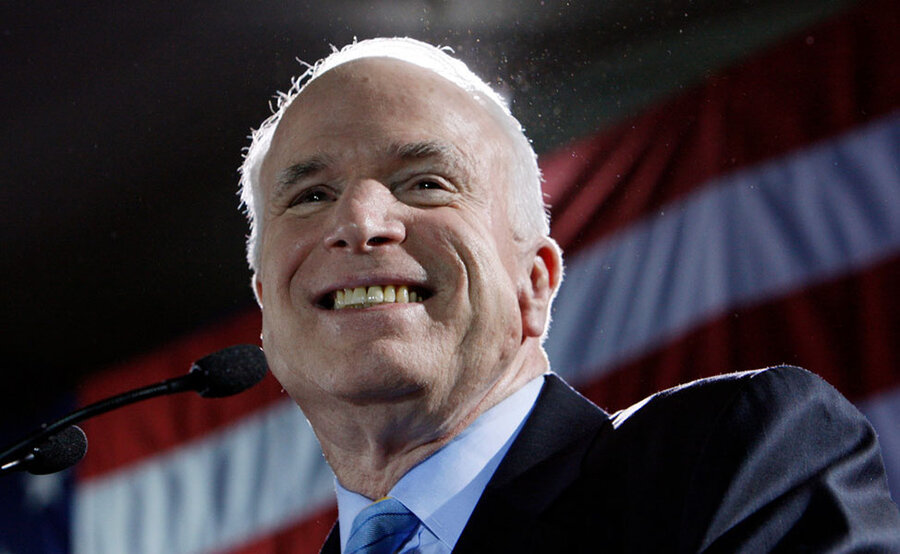

Remembering John McCain, a world-class reader

Loading...

In the many tributes that have been paid to John McCain over the last few days, he has been praised as a warrior, prisoner of war, leading member of Congress, presidential candidate, and statesman. Despite their differences with him, many if not most commentators have been quick to praise McCain as a great American.

But there's another group also quietly mourning McCain's passing last week. These are book lovers, saddened by the loss of an active and passionate fellow reader.

One of McCain’s role models was Teddy Roosevelt, another political leader who was also an avid bibliophile. For Roosevelt, a man perpetually on the go, reading wasn’t a passive act, but a wellspring of inspiration for a fully engaged life. McCain used books in much the same way, drawing on literature as a source of intellectual and spiritual sustenance.

McCain often mentioned his abiding connection with Ernest Hemingway’s "For Whom the Bell Tolls," a book he discovered by accident as a teen when he pulled the book from his father’s shelf to press some clovers he’d found in the yard. McCain regarded the book’s hero, an American professor named Robert Jordan who volunteers to fight in the Spanish Civil War, as a model of what a leader should be. “For a long time, Robert Jordan was the man I admired above almost all others in life and fiction,” McCain told readers of his 2002 memoir, "Worth the Fighting For." “He was brave, dedicated, capable, selfless, possessed in abundance that essence of courage that Hemingway described as grace under pressure, a man who would risk his life but never his honor.”

The title of "Worth the Fighting For" comes from something that Jordan says as he contemplates his mortality. McCain quoted the line in full in his final book, "The Restless Wave," published this year: “The world is a fine place and worth fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.”

When he was a presidential candidate in 2008, The New York Times, in a piece called "How to Read Like a President," also noted that McCain had a great enthusiam for the stories of W. Somerset Maugham, “The Great Gatsby,” “All Quiet on the Western Front,” and James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, especially “The Last of the Mohicans.” The Times also noted that he had twice read Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

There was also some space for poetry in McCain's literary samplings. He liked to quote from a poem by Robert Louis Stevenson: “Glad did I live and gladly die, / And I laid me down with a will.” The poem, “Requiem,” appears on Stevenson’s tombstone:

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie

Glad did I live and gladly die

And I laid me down with a will

This be the verse you grave for me

Here he lies where he longed to be

Home is the sailor home from the sea

And the hunter home from the hill

McCain’s admiration for Stevenson is understandable. The Scottish writer celebrated for his poems, essays, and travelogues, as well as novels such as "Kidnapped" and "Treasure Island," was seriously ill through much of his short life. Living so closely with the risk of death gave Stevenson a deep sense of urgency to get things done, to make his mark.

The prospect of death also shadowed McCain as a naval aviator and prisoner of war in Vietnam. That grasp of life’s fragility shaped his sense of purpose and ambition.

Stevenson’s long periods of convalescence forced him to marshal his mind against the hardships of confinement. His children’s poem, “The Land of Counterpane,” captures the way that imagination can liberate a body bound by circumstance to a single room.

McCain drew on similar mental resolve to survive his harsh imprisonment. To sustain their sanity, McCain and fellow prisoner Bill Lawrence, who was in a cell next door, would use coded taps to recite poetry to each other through the wall.

In the final months of his life, McCain sought solace at his beloved Arizona ranch.

Like Stevenson, McCain, who had traveled the world as a celebrated senator, perhaps sensed that life’s most profound moments are spent at home.

“You may paddle all day long,” Stevenson wrote, “but it is when you come back at nightfall, and look in at the familiar room, that you find Love or Death awaiting you beside the stove; and the most beautiful adventures are not those we go to seek.”

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.