Before Rachel Dolezal, there was Walter White

Loading...

Walter White, known as “Mr. NAACP,” didn’t look black. He had blue eyes and blonde hair, and his enemies sought to smear him as an opportunist who lied about his race and couldn’t possibly understand the black experience. But the secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People persevered through much of the 20th century and left a stunning if tarnished legacy.

White energized the refined halls of the NAACP, brought together literary stars of the Harlem Renaissance, and helped craft the partial demise of segregation. He battled lynching, convinced politicians to kill the Supreme Court nomination of a racist and hobnobbed with the famous. Sixty years after his death, White is eclipsed in modern memory by other civil-rights leaders. Few know about his remarkable struggle to be seen as the genuine article by other African-Americans, and his vicious battles with fellow leaders like W. E. B. DuBois.

But this month, the ever-bubbling issue of blackness – who has it, who doesn’t, and why it matters – is on tongues across the country amid the roaring debate over Rachel Dolezal, a NAACP official in Spokane, Wash. White’s story resonates as Dolezal, who may not be black as she’s claimed, faces a national storm.

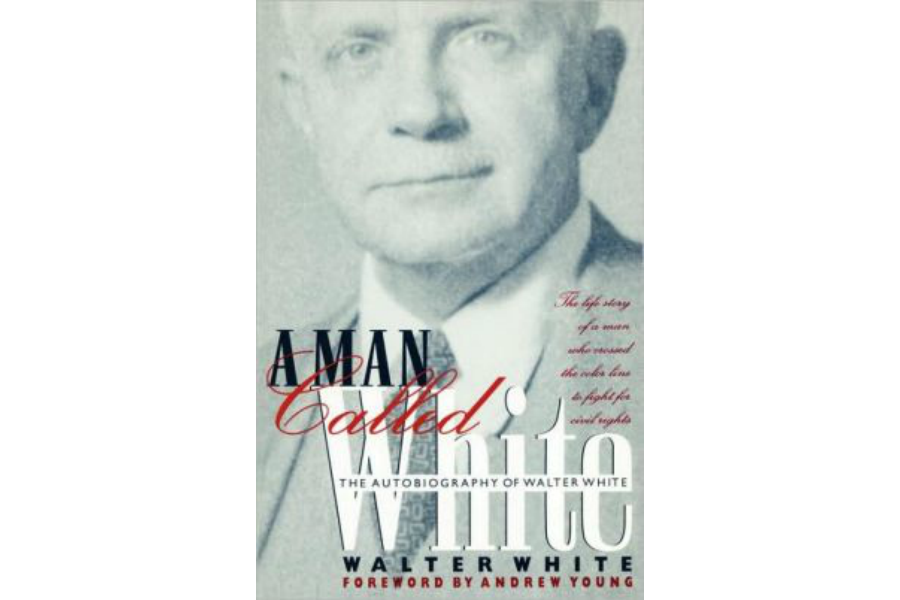

Here are 5 Things to Know about Walter White and Racial Identity, gleaned from his crisply written 1948 memoir A Man Called White and author Thomas Dyja’s perceptive and often-critical 2008 biography Walter White: The Dilemma of Black Identity in America.

1. ‘Passing’ saves White’s life

White begins his memoir with an anecdote about standing on a subway platform in Harlem and accidentally stepping on a black man’s foot. The man looks at him with a face “full of the piled-up bitterness of a thousand lynchings and a million nights in shacks and tenements and ‘nigger towns’: ‘Why don’t you look where you’re going? You white folks are always trampling on colored people.”

The man is chagrined to learn that White is a black man, and not only that, the famous secretary of the NAACP too.

White was a longtime veteran of mistaken racial identity, dating back to his childhood in a family of light-skinned blacks. As he tells it, he escapes his own murder in Arkansas while visiting during an anti-lynching campaign. A railroad conductor doesn’t realize he’s the black man “passing for white” who’s to be murdered. “You’re leaving, mister” the conductor says while allowing him on board, “just when the fun is going to start.”

Appearing to be white brings him other advantages. Once he gets a “white” job in college, biographer Dyja writes, and he doesn’t correct the record. On the other hand, he goes to a special high school because Atlanta doesn’t provide education at that level to blacks.

2. He defines his race himself

As Dyja writes, White was – by one definition – 5/32nd black. He could have put himself “on the fringes of his race,” or have simply foundered thanks to his own understanding of the “inexplicable” divided between his skin and his soul. Instead, “he always felt black because, in the most primal sort of identity politics, he had defined blackness as the way he saw the world.”

3. White’s recounting of the 'facts' of his life may have been unreliable

The best memoir writers must struggle with issues of honesty and the hazards of relying on memory. Dyja suggests that White, a relentless self-promoter, wasn’t devoted to the truth. A story he often told about encountering a white Atlanta mob as a child morphed into a tale of him wielding a gun, ready to fire to defend himself as a black person. The truth, Dyja writes, “mattered less to White than making his greater point, advancing his cause and making himself look good.”

At the same time, Dyja writes, White fails in one area of self-marketing: He doesn’t do enough to push his own case (that he’s black) to the African-American community. White, Dyja writes, simply assumes blacks “knew and believed he was working for all their interests, not just his own.” This assumption would haunt him.

4. Nemesis challenges his blackness

W. E. B. DuBois, an African-American intellectual and top Civil Rights figure, fought with White over control of the NAACP in the 1930s. Not that you’d hear this from White: He barely mentions DuBois in his 1948 memoir. But the battle was real. Amid infighting within the NAACP, DuBois lands a haymaker: He claims his nemesis is not black and has no knowledge of being black in the US. But White would ultimately win the fight over the fate of the NAACP. As Dyja writes, DuBois loses and abandons the organization, “taking some of the black intelligentsia with him.”

5. A white woman sealed his fate

In 1949, a year after White’s memoir comes out, he divorces his wife from a loveless marriage, resigns from the NAACP and marries a white woman. While it wasn’t unusual for Civil Rights leaders to woo or marry white women, his action infuriates the black community, Dyja writes: “Every question, suspicions and qualm ever he’d against him – and there were many – now came roaring out.” Even members of his own family turned against him.

Amazingly, he follows up by writing a magazine article about how the science of skin-lightening could eliminate race forever by making everyone white.

That is it, Dyja writes. His legacy – forever trimmed by his ego – is now tarnished for good. In a few years, he will pass away. Decades later, a president who’s half-black and half-white will be called a black man, but never a white one. And amid the never-ending divides of American life, we’d continue to fight over who is us and who is not.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.