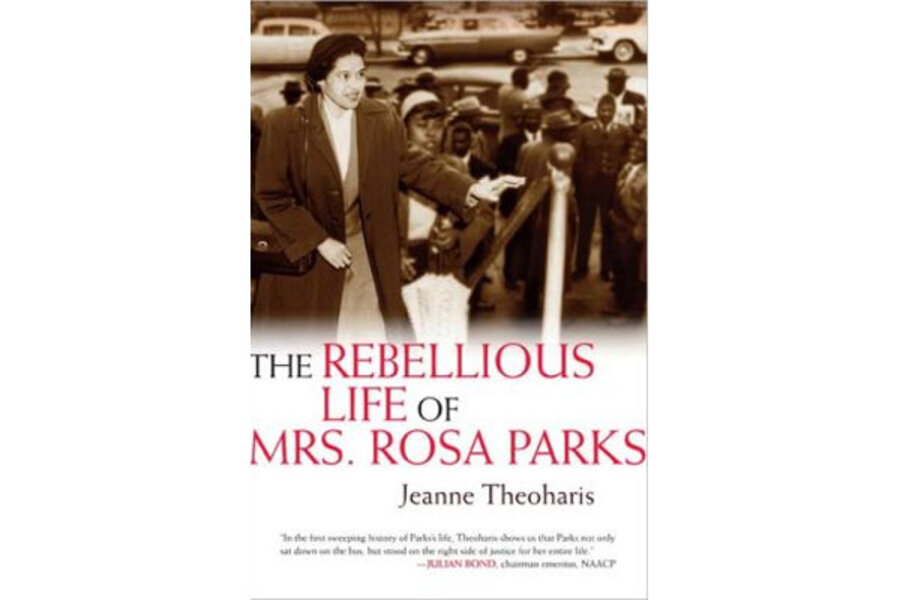

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks

Loading...

Already designated “definitive political biography” on its back cover, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Brooklyn College political science professor Jeanne Theoharis will reside in my personal reading history as the most difficult book I’ve ever reviewed. Never before – and hopefully never again – have I faced such a vast divide between significant content and frustrating execution. As the most exhaustively researched biography thus far on Rosa Parks, Theoharis’ new title is inarguably an essential addition to any library or classroom, and yet readers will need serious patience to sift through tedious repetition, fragmented chronology, and countless "might have/could have" assumptions to reach the final page.

Fable, myth, caricature are not words historically linked to Rosa Parks, who is publicly remembered as the quiet, tired seamstress whose refusal to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Ala., bus sparked the US civil rights movement. When she died at 92 in 2005, Parks became the first woman and second African American to have her body lie in state in the US Capitol Rotunda; 40,000 – including President and Mrs. George W. Bush – bore witness, with additional mourners paying tribute at overflowing memorials held in Montgomery, and Detroit, where Parks spent more than half of her life.

“[T]he woman who emerged in the public tribute bore only a fuzzy resemblance to Rosa Louise Parks,” Theoharis proves. “[R]epeatedly defined by one solitary act on the bus,” Theoharis insists Parks was “stripped of her lifelong history of activism and anger at American injustice.” Instead, “the public spectacle provided an opportunity for the nation to lay rest a national heroine and its own history of racism.” In other words: 50 years earlier, this tired woman couldn’t sit on a bus, but look where she’s lying now.

Theoharis “was captivated and then horrified by the national spectacle made of her death.” She gave a talk about “its caricature of [Parks] and, by extension, its misrepresentation of the civil rights movement,” which she was asked to turn into an article: “It became clear how little we actually knew about Rosa Parks.” Even "Rosa Parks: A Life," the biography by lauded historian Douglas Brinkley, "is “pocket-sized, un-footnoted,” while the autobiography Parks wrote with Jim Haskins, “Rosa Parks: My Story,” is targeted for young adult readers. “[T]he lack of scholarly monograph on Parks," Theoharis observes, "is notable.”

More than a personal biography, “The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks” (Theoharis uses the honorific Mrs. to add "a degree of dignity, distance, and formality to mark that she is not fully ours as a nation to appropriate") is a political reclamation of Parks’ almost-70 years of activism. As the grandchild of slaves, Parks knew “[f]rom an early age, ... ‘we were not free.’” Pushed by her mother, a teacher, towards an education, “her discovery of black history in high school was transformative.” Family responsibilities kept Parks from finishing 11th grade; she wanted to be nurse or social worker, never a teacher after the “’humiliation and intimidation’” she watched her mother endure. Her husband Raymond Parks was “’the first real activist I ever met.’”

Her acts of resistance began small and early – she refused to drink from segregated water fountains – then public and even life-threatening – she registered to vote and assisted others “despite enormous poll taxes and the unfair registration tests.” She was Montgomery’s NAACP secretary, long aligned with controversial activist E.D. Nixon; she experienced interracial leadership training and race equality at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee.

This was the seasoned, knowledgeable Parks who boarded an evening bus on December 1, 1955, and refused to give up her seat – she was the third, not first, African American woman who refused to get up, but unlike the previous two who were teenagers, Parks was “middle-aged, religious, of good character … respected.” Her arrest sparked a year-long bus boycott that catapulted young Martin Luther King, Jr. into the spotlight, and changed history forever.

Her courage had severe personal consequences, conveniently elided by history. She lost that seamstress job – she was actually a skilled “assistant tailor,” another detail overshadowed by her humbling myth. Raymond lost his. Her mother fell ill, Parks herself was riddled with ulcers, Raymond drank heavily. The family was constantly harassed. Parks reluctantly traveled without pay across the country at the behest of fellow male activist leaders; as “the proper kind of symbol,” Parks was regularly seen but rarely heard.

Unable to find work in Montgomery, the Parkses moved to Detroit to join family, and spent a decade suffering dire financial straits; the hate mail and death threats continued. The “Northern Promised Land” had all the same civil rights challenges as the South, yet Parks never lost hope, continuing her activism for almost another half-century. She found inspiration in the Black Power movement, protested wars, fought to educate and empower the youth, even after she was mugged in her own home. Financial stability finally came with her “first ... paid political position” in the office of US Congressman John Conyers which would last over 20 years.

With Parks’ death, her literal history became mired in legal disputes. Although the “‘first’ installment” of her papers were donated to Wayne State University in 1976, “a vast trove ... sits in a storage facility in Manhattan, of use to no one, priced at $6 million to $10 million.” The “celebrity auction house,” Guernsey’s, has been trying to sell the Rosa Parks Archive for five years, “steadfastly unwilling to let any scholar make even a cursory examination.”

February 4 marks Parks’ 100th birthday: the Archives’ release could be a most significant public gift. Until that happens, Theoharis’ “Rebellious Mrs. Parks,” in spite of frustrating flaws, provides the most illuminating, necessary insight into a needs-to-be-retired legacy that deserves heightened attention and renewed respect.

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book review blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program.