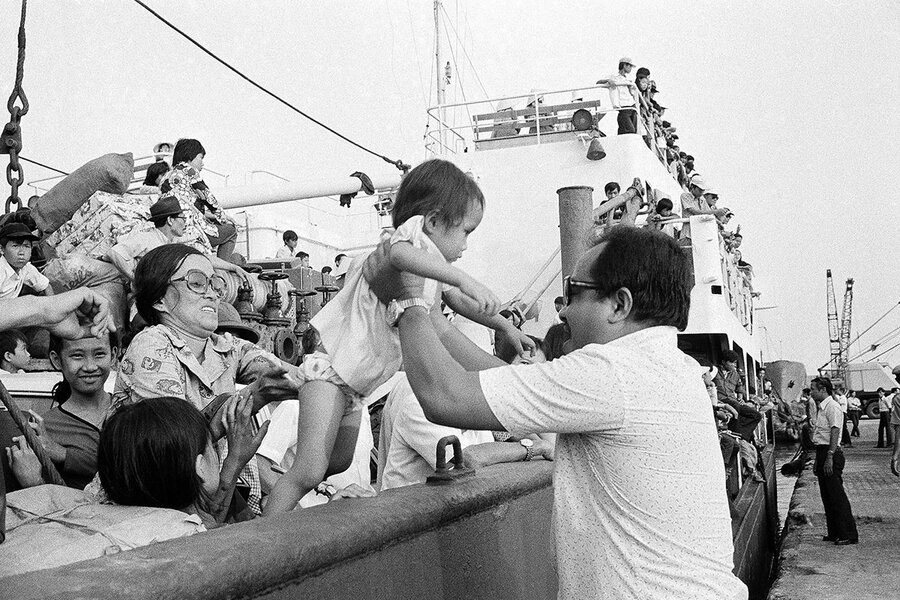

The fall of Saigon split families apart. Hers was among them.

Loading...

Beth Nguyen was 8 months old when her father, uncles, and grandmother whisked her and her sister out of Saigon, Vietnam, the day before the city fell to the North Vietnamese army in 1975. After stops in three refugee camps, they eventually settled in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

In her new memoir, “Owner of a Lonely Heart,” Nguyen marvels that “so much of my life hearkens back to a time that I can’t remember and didn’t choose.” The powerful, searching narrative probes two momentous consequences of her quick exit from Vietnam, during which her mother was left behind: She grew up as a refugee in America, and she didn’t see her mother again until she was 19 years old.

“Over the course of my life I have known less than twenty-four hours with my mother,” the author explains at the outset. Those hours elapsed during six visits in 26 years. They took place in Boston, where Nguyen’s mother was resettled after she herself became a refugee, a decade after her daughters did.

Why We Wrote This

Beth Nguyen wrestles with vital questions of family, loss, and memory, giving voice to the often overlooked contours of grief – and encouraging readers to reflect on their own relationships.

Nguyen remembers her father abruptly telling her when she was in fifth grade, that her mother, about whom they rarely spoke, had come to America. She reflects upon why she and her sister asked so few questions about this unexpected mention of their absent parent. Part of it had to do with Nguyen’s distant relationship with her father, a taciturn and quick-tempered man with whom the author had difficulty connecting.

But Nguyen believes that there was another reason as a child she didn’t pursue more information about her mother. “It was troublesome enough being Vietnamese in our conservative white town,” she notes. “There was already so much to conceal from our white friends, so many ways to pretend that we were just like them.”

Being a refugee was an isolating experience for the author. “Refugees don’t fit the romantic immigrant narrative that’s so dominant in America,” she observes. “They are a more obvious, uncomfortable reminder of war and loss.” She felt, as she elegantly puts it, “both too seen and unseen.” In an especially penetrating chapter, a version of which appeared in The New Yorker, she describes how her given name, Bich – common in Vietnam but an albatross for her in her adopted country – exacerbated feelings of shame that she came to associate with the refugee status she could not shake, even after becoming an American citizen.

“As Bich, I am a foreigner who makes people a little uncomfortable,” she writes. “As Beth, I am never complimented on my English.” (The author’s earlier books – a memoir, “Stealing Buddha’s Dinner,” and two novels – were published under the name Bich Minh Nguyen; she started going by Beth in her 30s.)

As a child, Nguyen didn’t lack mother figures. When she was 3, her father married a woman whom she is close to and calls “Mom”; it was her stepmother who helped foster her love of books with regular trips to the local public library. Her indomitable grandmother lived with the family, providing the stability and love that Nguyen didn’t get from her father. She was, Nguyen writes, “the life force of our family.”

But it is Nguyen’s cautious and halting connection to the woman she calls her “Boston mother” that gives this aching memoir its shape. Their visits are always brief; the author often spends considerably more time getting to and from her mother’s apartment than she spends inside it. Nguyen asks her mother about Vietnam, her past, and, especially, how she felt on the day in 1975 when she discovered that her children were gone. Most often, Nguyen’s questions are dismissed with clipped responses or a wave of the hand. They aren’t close. As the author writes, “Our histories had separated long ago and had never truly met again.”

Nguyen insists throughout the book that it is easier to remain detached from her mother. “Once you are gone, it gets easier to stay gone,” she writes. And elsewhere: “I now know the strange secret of this: absence gets easier, not harder.” And elsewhere: “It is easier, in the end, to keep your distance. You let what is unraveled stay unraveled.” Both the author and her sister are married, and neither invited her mother to her wedding. “We hadn’t told our mother about our weddings because it was simpler not to.”

Of course, such claims must be weighed against the very existence of a memoir devoted to this unusual mother-daughter relationship, as distant and formed by loss as it is. Early in the narrative, Nguyen, who has two sons, mentions that when she brought her first child to Boston at age 1 to meet her mother, her mother didn’t show up, choosing to go gambling at a casino instead. They wouldn’t meet again for seven years.

The author shrugs it off, writing, “I couldn’t blame her for wanting to try her luck elsewhere,” but one assumes the rejection must have been painful in the moment. Meanwhile, her mother’s reasons for skipping their date are unknowable.

Nguyen compares her mother’s absence with her own presence as a parent, citing her relief when her children reached an age at which they’d remember her no matter what happened. Motherhood, of course, is heavily freighted, at both a cultural and a personal level. Perhaps there is no easy way out.