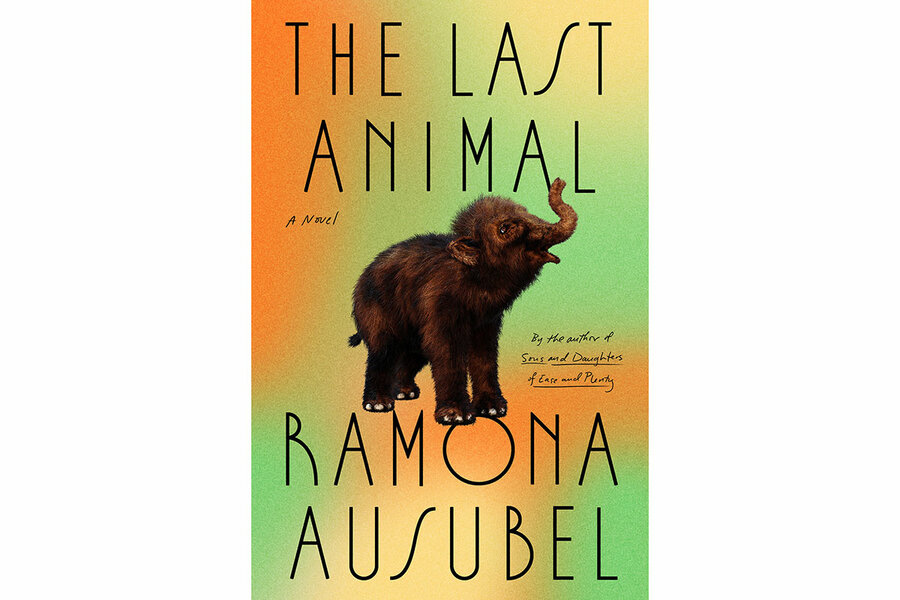

Reviving woolly mammoths and a mom’s relationship with her daughters

Loading...

Women scientists, long given a raw deal in labs, are having their day in novels. Last year, Bonnie Garmus’ enormously popular “Lessons in Chemistry” introduced a brilliant, mistreated research chemist who found unexpected, sweet revenge as host of a provocative cooking show that dared women to rethink their life recipes.

Now we have Ramona Ausubel’s “The Last Animal,” which features another scientist, also a single mother and widow of a fellow scientist. Ausubel’s ambitious heroine is tired of being “twice as capable and half as appreciated” as her male co-workers in the Berkeley paleontology lab where she is working her way through graduate school.

We meet Jane on a summer expedition to Siberia led by her boss, whom Jane refers to as “my professor,” but whom her late husband, Sal, a prominent anthropologist, referred to as one of those “de-extinction wackos.” The group’s mission is to unearth woolly mammoth bones in order to extract DNA in the hopes of someday bringing back these lost Ice Age creatures.

A year after her husband’s death in a car accident in Italy, Jane is still passionate about human evolution, adaptation, and the devastation of our planet, but she is struggling emotionally and financially. Regrettably, her role as her husband’s assistant on his highly acclaimed book about an ancient humanoid dubbed “the iceman” unearthed in Northern Italy has left her with no marketable credentials of her own.

Along for the ride – though not happily – are Sal and Jane’s daughters, Eve and Vera, 15 and 13. The girls are used to far-flung travel, having spent much of their childhood on research expeditions with their parents. But they miss their father and hate seeing their mother belittled by her male colleagues. They wish they were in summer camp.

The idea that a graduate student with no clout would be allowed to bring kids along “to the edge of the world” strains credulity, but that’s just the tip of the proverbial iceberg of this novel’s outlandish albeit endearing improbabilities. Ausubel has concocted a wild and woolly global escapade about unbounded scientific experimentation. Yet what comes into sharpest focus under her authorial microscope are mother-daughter and sister relationships.

For much of the novel, Jane is a terrible mother. She sees her children as “neon signs of her age, her widowhood, her inability to be her own kind of success.” In her distraught state, she unloads too much on them – her grief, her worries, her frustrations, her pressure to build a career that will support them and satisfy her dreams. At one point she complains, “I’m a thirty-eight-year-old graduate-student single-mother widow. You couldn’t string together a sadder list of attributes if you tried.” Sensitive, responsible Vera says, “Do you hate your life that much?”

The two smart, competent sisters are a tight duo, wonderfully delineated. It’s no surprise that, far from being a liability, they turn out to be an asset – beginning with a remarkable find in the permafrost that briefly raises their mother’s stature.

Practical Vera, who loves to bake and turn pain into pastry, longs for a more conventional, settled existence – and a more attentive mother who sets boundaries. “She had been raised to imagine greatness, difficult and brave work, but she mostly wanted something steady.”

Eve is restless. Unlike Vera, who worries about the climate crisis and is determined to fix it, Eve’s attitude is that since the earth is doomed, they might as well have fun with what’s left. Which is what she tries to do when her mother’s next expedition takes them to Iceland to study the genetic signature of the remote island nation’s pure-blooded population.

Ausubel’s tale of grief and grievances morphs into a “four women and a fairy tale” caper after Jane, fed up with never being credited for her ideas, impulsively decides to initiate her own experiment. She cooks up a plan with a wealthy Italian named Helen who keeps exotic animals – including a pachyderm of breeding age – on her husband’s castled estate on Lake Como. Jane’s obsessive fervor for this rogue experiment leaves the girls, who distrust Helen’s motives, feeling downright endangered. “Are you still our mom?” Eve asks as the neglected sisters vie for their mother’s attention.

“The Last Animal” is a hairy but cuddly beast of a novel that sheds life lessons, some heartwarming, many sticky with sentiment. Jane has brought up her daughters to understand that “Life is experiments.” But she also wants them to know that it is filled with improbabilities, an “ever twistier road,” and that “The fantasy is always better before it comes true. That’s a life truth.”

So what to do? Play it safe, or go for greatness? Look to the past, or to the future? What about the present? Ausubel’s conclusion is clear: Nurture the earth and your dreams, but don’t forget to nurture your family: “They mattered to one another, now, alive, and that was the whole gift.”

Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for the Monitor, The Wall Street Journal, and NPR.