‘After the Miracle’ spotlights Helen Keller’s political crusades

Loading...

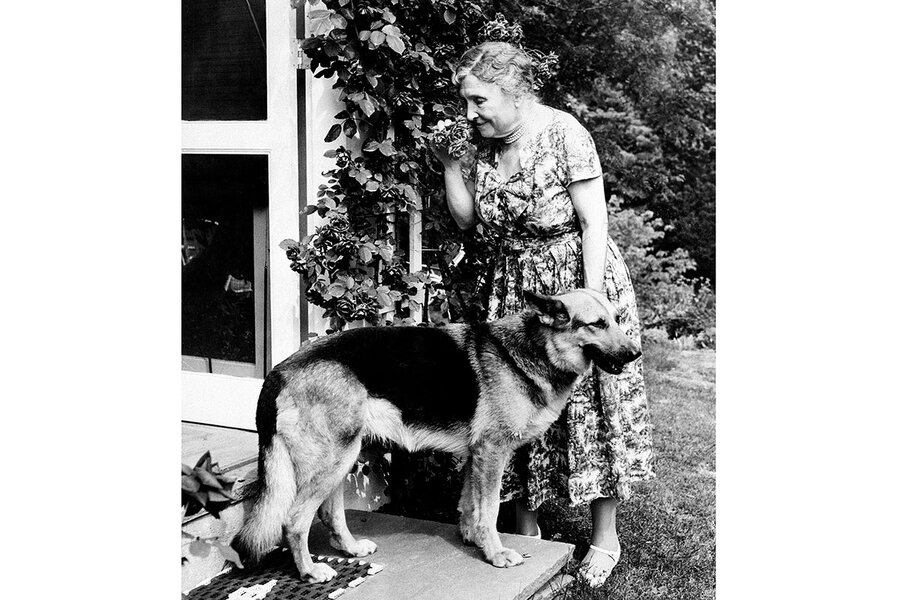

Helen Keller achieved international fame as a young deaf and blind girl who learned to read, write, and speak. But while the story of her early years is widely known, fewer people are aware of how Keller used her fame for the remainder of her long life. In the illuminating “After the Miracle: The Political Crusades of Helen Keller,” Max Wallace highlights Keller’s abiding devotion to radical leftist causes, which included speaking out against Jim Crow, Nazism, McCarthyism, and more.

Wallace, an author and advocate for people with disabilities, argues that because Keller’s political activity invited controversy – she was an avowed socialist – many have preferred to remember her merely as an inspirational child. “No matter the significance of events that took place in Alabama when Helen was six,” he writes, “they have served to largely overshadow or erase the extraordinary eighty years of her life that followed.”

The author doesn’t neglect the familiar narrative, opening the book with a summary of his subject’s Southern childhood. Born in 1880, Keller contracted an illness at 19 months that left her blind and deaf. Anne Sullivan came to live with the Keller family when Helen was 6 years old, to serve as the child’s private teacher.

Sullivan began to spell words with her finger into her pupil’s hand. Within weeks they experienced the breakthrough at a water pump that was immortalized in “The Miracle Worker,” which premiered as a TV movie in 1957 and was later adapted into a Broadway play and feature film. As Sullivan spelled the word “water” into Keller’s hand while water from a pump rushed over the other, young Helen made the connection between words and objects. Her education progressed quickly from there.

Alexander Graham Bell was among those who spread word of her accomplishments. (Bell’s mother and wife were deaf, and he had long been involved with research into hearing and speech.) Keller developed a friendship with Mark Twain that lasted until the author’s death in 1910. He is said to have called Keller and Napoleon the two most interesting people of the 19th century. She was invited to the White House to visit Grover Cleveland, the first of 13 U.S. presidents she would meet during her lifetime.

Sullivan taught Keller Braille, and as she began to read voraciously, Keller formed the political convictions that made her, in Wallace’s words, “a radical socialist firebrand.” She wrote and lectured in support of socialism and against the excesses of capitalism; she was interested in the connections between industrial accidents and blindness. She was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union and an early supporter of the NAACP. “It should bring the blush of shame to the face of every true American to know that ten million of his countrymen are denied the equal protection of the laws,” she wrote in 1916.

Keller and Sullivan lived together until the latter’s death in 1936. They were always concerned about money: The author describes a four-year period when the two women earned their living on the vaudeville circuit, performing a scripted show about Keller’s life. For decades, Keller supported herself and Sullivan by working as the official fundraiser for the American Foundation for the Blind. (Interestingly, she did little to advocate for the deaf community.) Wallace quotes from communications that reveal the organization’s discomfort whenever their unruly spokeswoman made public statements on hot-button issues of the day.

While Keller’s radicalism is fascinating, the author occasionally overstates its impact. She spoke out early against Hitler and Nazism, and her books were among those banned in Nazi Germany. But Wallace goes a bit far when he insists that “the woman who most people still pictured as a saintly apostle of love and understanding demonstrated that her words had enough sting to make even the world’s most ruthless dictator tremble.”

Even if there’s little evidence that she made Hitler tremble, Keller was undoubtedly courageous in expressing her convictions, often during periods of political repression. As Wallace observes, she was insulated by the goodwill built up toward her over decades, even during the Red Scare, when her pro-Soviet statements aroused the interest of the FBI. “Helen’s iconic status continued to help immunize her from the fallout over her political beliefs,” he writes. Her activism did little to harm her reputation for another more disturbing reason that the author cites: some people, doubting “her ability to come to her own intellectual conclusions,” assumed that her opinions could only be “the result of manipulation.”

When she encountered such condescension, Keller generally offered a biting response. “It would be difficult to imagine anything more fatuous and stupid than the attitude of the press toward anything I say on public affairs,” she once remarked. That’s another thing the sentimentalized version of Helen Keller omits and that Wallace’s compelling book captures: She did not suffer fools gladly.