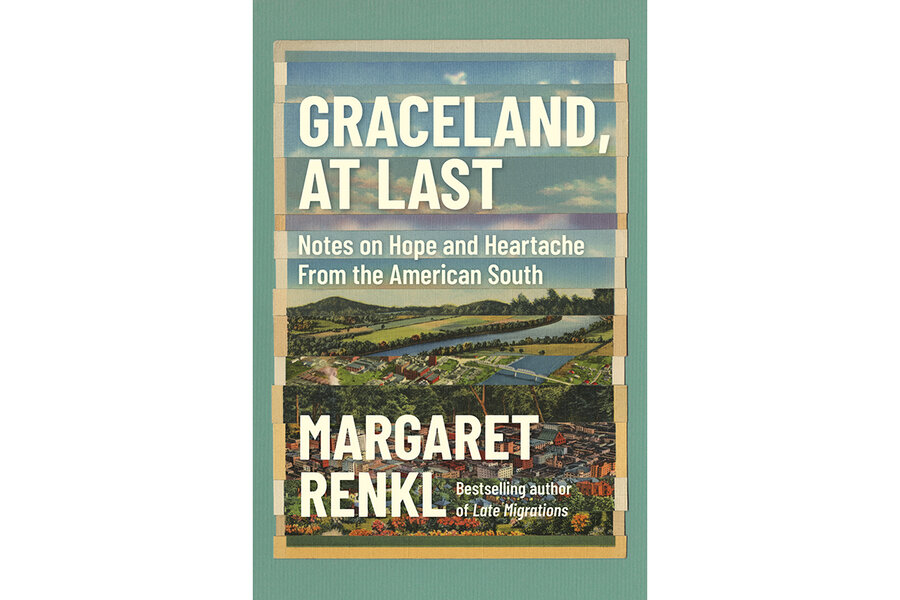

‘Graceland, At Last’ unfolds a Southerner’s wise and hopeful essays

Loading...

Since 2017, from her home in Nashville, Tennessee, Margaret Renkl has written a column for The New York Times that covers, as the paper puts it, “flora, fauna, politics and culture in the American South.” She made a splash in 2019 with “Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss,” a fragmentary memoir that repurposed some of the material from her column. It was a good book that invited Renkl’s fans to wonder when a more conventional collection of her columns might be published. In “Graceland, At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache From the American South,” they have a welcome answer.

Renkl is a lovely writer, and to read her work is to be reminded that as a younger woman, she once aspired to be a poet. In one sense, she’s realized that dream; her lyrical sentences sing from the page. In an August essay from last year, when pandemic lockdowns were in full swing and more trouble was on the national horizon, Renkl mused on a mole in her backyard: “In these days that grow ever darker as fears gather and autumn comes on, I remember again and again how much we all share with this soft, solitary creature trundling through invisible tunnels in the dark, hungry and blind but working so hard to move forward all the same.”

Passages like that one underscore Renkl’s sublime style. But it’s no discredit to her to consider the fact that without her regional roots, Renkl might not have been chosen to write a regular column for the Times. Her role, both a privilege and an abiding complication, is apparently to be a Great Explainer of All Things Southern to the rest of the country.

Renkl seems deeply aware of how thorny – and potentially limiting – that job can be. “I’m not the voice of the South,” she offers as a disclaimer, “and no one else is, either, because in truth there’s no such thing as ‘the South.’”

In “What Is a Southern Writer, Anyway?,” one of the book’s wisest essays, Renkl echoes many other commentators as she suggests that in a globalized economy, old regional distinctions aren’t as sharp. “Far more urban, far more ethnically and culturally and politically diverse, the South today is no longer a place defined by sweet tea and slamming screen doors, and its literature is changing, too,” she writes.

But Renkl doesn’t entirely discount a special role for writers in her part of the world. “Maybe being a Southern writer is only a matter of loving a damaged and damaging place, of loving its flawed and beautiful people, so much that you have to stay there, observing and recording and believing, against all odds, that one day it will finally live up to the promise of its own good heart.”

This wounded condition, a legacy of the South’s fraught history, seems an analog of sorts for America’s current national mood. In the wake of a pandemic and racial and political strife, the broader culture also seems ill at ease. It’s why Renkl’s essays, though written by a child of the South, resonate with particular urgency.

Her eloquent essays about the environment, often based on her backyard observations, are especially apt metaphors for these national injuries. “During my childhood in Alabama,” she recalls, “every highway and back road was alight with butterfly weed, which belongs to the family of milkweeds. In summer it formed a bright corridor of orange flowers so covered with orange monarch butterflies that from a distance it looked as though the flowers themselves were taking flight and floating on the breeze.” But Renkl notes that many factors, including the widespread use of herbicides that kill food supplies for monarchs, have sped their decline.

It’s heartening to see a columnist for a major American newspaper writing regularly about nature with a passion the media’s chattering classes typically reserve only for politics and entertainment.

Renkl’s essays invite comparison with those of Brooks Atkinson and Joseph Wood Krutch, two journalists of an earlier generation who also traversed easily between columns on nature, culture, and the work of the government. Atkinson was a Times theater critic who wrote perceptively about woods, water, and sky. Krutch, also a theater critic, was an equally deft chronicler of nature, particularly in the Southwest.

Renkl’s noteworthy predecessors, largely forgotten today, understood that the work of literature and art, governance and the great outdoors are inextricably linked – part of the great chain of being that defines the human condition.

American readers have erred in letting the likes of Atkinson and Krutch lapse into obscurity. “Graceland, At Last” is a timely reminder of what they’ve been missing. Renkl’s columns deserve to be read again, and for years to come.