‘The Outlier’ paints a complex portrait of Jimmy Carter

Loading...

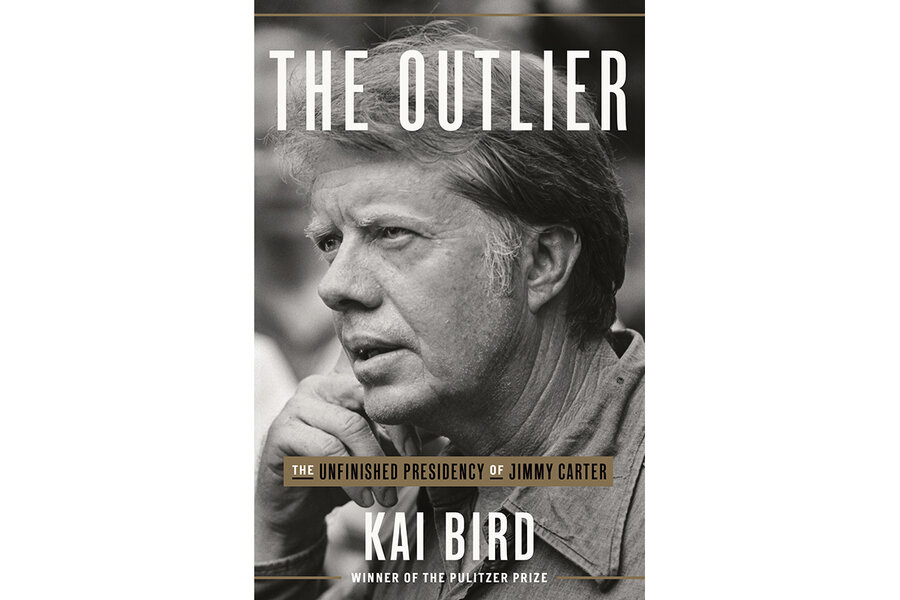

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Kai Bird’s book “The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter” seeks to renovate the legacy of the Carter administration in the only way likely to succeed: by adding to the scales of judgment an enormous amount of research and a refreshing lack of partisanship.

Considering the fact that Carter’s single term in office is routinely caricatured as a mess of domestic malaise (long lines at the gas pumps and stagflation) and international impotence (the Iranian hostage crisis), it hasn’t lacked for good histories. In recent years alone, there was Nancy Mitchell’s excellent 2016 foreign policy analysis “Jimmy Carter in Africa: Race and the Cold War,” Stuart E. Eizenstat’s brilliant but biased 2018 book “President Carter: The White House Years,” and Jonathan Alter’s affectionate “His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life” from last year. And back in 1982, there was “Crisis: The Last Year of the Carter Presidency” by Carter adviser Hamilton Jordan, which remains one of the most frank and gripping White House memoirs of the modern era.

All such accounts, however disparate, convey more or less the same impression of the man himself: Carter was a Southern Democrat, an engineer, an idealist, and a perfectionist. But even the friendliest renditions admit he could be a mulish martinet, fussily prone to getting stuck in the weeds of any issue, and oddly thin-skinned for a man in public service. “He tended to think that he was the smartest fellow in the room. And he probably was,” Bird writes in “The Outlier.” “But he also had a stubborn streak and a surprising audacity. His self-confidence bordered on arrogance.”

Bird admits at the outset of his fluidly engaging book that Carter was and remains an enigma. He was a one-term president regularly dismissed as a failure who nevertheless accomplished a great deal in his term – a whip-smart intellectual who sometimes read 250 pages of memoranda a day but who had nothing but scorn for the realities of Washington politics. “He was astonished at the pettiness of the key senators sitting on the fence,” Bird writes about one such moment of frustration. “Carter just wanted them to do what they knew was the right thing.”

In “The Outlier,” Bird dramatizes the challenges faced by the Carter administration by bringing to life the people involved. The book has vibrant personality portraits of everybody from New York State politician Midge Costanza, the first woman ever named a presidential assistant, all the way to Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s prickly and imperious national security adviser. (“Like Carter,” Bird shrewdly observes, “Brzezinkski liked to make the occasional joke, but rarely at his own expense.”)

Bird’s Carter is “a man who always had to be doing something – building something, reading something, or catching a fish.” But he could also be self-pitying and impulsive, prone both to moodiness and pickiness. He expected his staff to work as hard as he did. “He was also a stickler for both punctuality and the written word,” Bird writes. “He hated incorrect grammar and the sloppiness of the typo.” This Jimmy Carter is not a saint – but he does come across as a fundamentally decent man who was stubbornly unwilling to surrender his decency, even in the face of challenges more severe than most presidents face.

The foremost of those challenges – the Iranian hostage crisis – naturally tends to overshadow the rest, but Bird gives ample attention to the other areas that Carter himself considered crucial to his administration. These include the normalization of relations with China, the treaties that would turn over control of the Panama Canal to Panama, the campaign for peace in the Middle East, and many others. In almost every case, Carter was as well-informed as all his experts – and therefore all the more irritated when that knowledge didn’t lead to results. His seething frustration at not being able to rescue the hostages in Iran leaps off these pages.

In the half-century since Carter left office, the country has witnessed Reaganomics, the longest war in American history, the unethical deployment of combat drones, and a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. An administration within living memory during which the president kept the peace, told the truth, and adhered to morality can seem like something out of a Hollywood fantasy like “The American President.”

The United States may never see another presidency like Jimmy Carter’s, and as time goes on his administration increasingly looks like an outlier, the very term Kai Bird uses for its chief. Readers could find no better place to learn about that anomaly than this book.