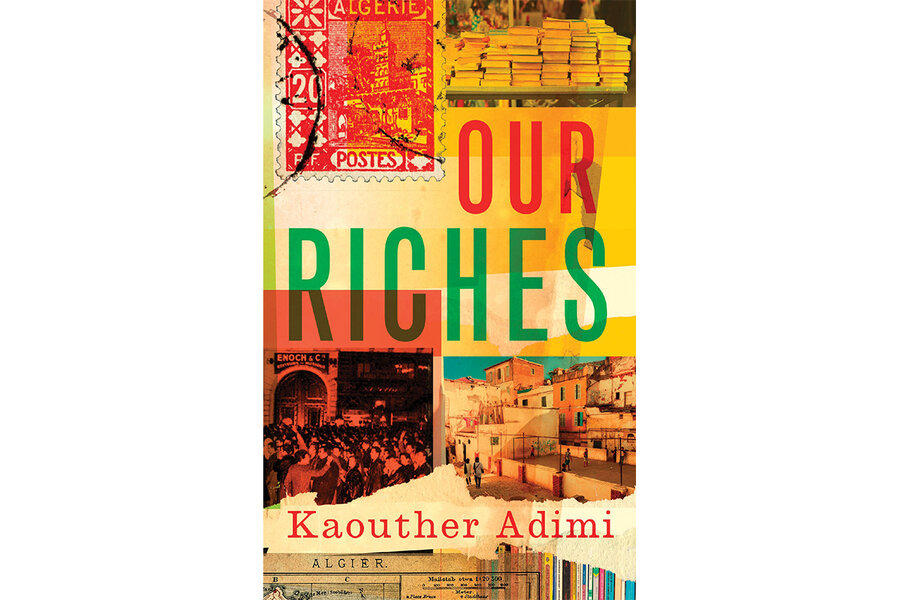

For the love of language: ‘Our Riches’ celebrates reading

Loading...

“Our Riches” is, quite simply, a book about books and the people who treasure them. The first English translation of a work by the French writer Kaouther Adimi, “Our Riches” weaves together two narratives – one fact and the other fiction – to tell the story of Les Vraies Richesses, the renowned Algerian bookstore and publishing house. The golden thread that runs through this historical novel is an appreciation for the written word.

First, the facts: Influential publisher and editor Edmond Charlot opened Les Vraies Richesses, or True Riches, in 1936. Then just 20 years old, Charlot scraped together every penny he could and staked his all on making the shop a viable business. He hung a sign reading “The young, by the young, for the young” outside, thus declaring his intention to create an intellectual outpost for a new generation.

In the years that followed, his enterprise expanded to become a publishing house as well as a lending library for the local community. It became home to prominent writers of the day, including Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (author of “The Little Prince”) and Albert Camus (whom Charlot discovered and first published).

The business prevailed almost in defiance of the geopolitical climate of its time – including the upheavals of World War II, as well as rebellions against the colonial forces that occupied African nations. It endured through paper shortages and the backlash of Nazi sympathizers who condemned bookstores for the freedom of thought they represented. Adimi shares this rich history via short entries in Charlot’s voice – ”journal” entries grounded in a year’s worth of her archival research and interviews.

Now, the fiction. Adimi juxtaposes history with a story set in 2017 featuring an apathetic engineering student named Ryad. The contrasts between the two young men, who come from wildly different eras but occupy the same physical space, burnish the power of the book’s narrative.

Ryad, born in Algeria but raised in Paris, returns merely to fulfill a degree requirement which involves an internship performing manual labor. His father got him the gig through a friend who happens to own a building that includes an abandoned bookstore. Ryad has his orders: Trash the books, destroy any remaining records, and give the whole place a fresh coat of paint. The owner of the building plans to turn the long-dormant space into a beignet shop, because “a beignet’s always going to be easier to sell here than a book.”

For readers who have watched many independent bookstores close, this story will seem all too familiar. But while book lovers might cringe at the idea of turning a bookstore – especially one of such immense cultural significance – into a bakery for commercial gain, Ryad has no such qualms. He has never really liked reading. “Those black characters printed on white paper remind him of mites,” Adimi writes. Besides, Ryad argues, any of these volumes can now be found online, so what does it really matter?

News of his arrival and his assigned task travels through the community at lightning speed. Abdallah, an older man who often lingers near the shop, tells Ryad how he used to work at the bookstore. Now homeless, he still regards it with a protective eye. Eventually, Ryad learns of the shop’s history as a lending library – in reality, an arrangement to help people read books who otherwise do not have the means of buying them.

In fewer than 150 pages, “Our Riches” reminds readers of the printed word’s ability to impart new ideas and shape public opinion. And the book shares an appreciation for the artistry within the publishing industry, whether it be the discovery of an emerging writer or the decision to prioritize beautiful bindings in the midst of wartime rationing.

Readers looking for a remarkable plot twist aren’t going to find one. Adimi is focused on the deep ties that multiple generations of neighborhood families have with Charlot’s bookstore. Throughout all time, of course, books and the spaces that support them have fostered community. Charlot knew that. Decades later, the people of his neighborhood still know that.

Most any bibliophile knows that. Books are, after all, our riches.