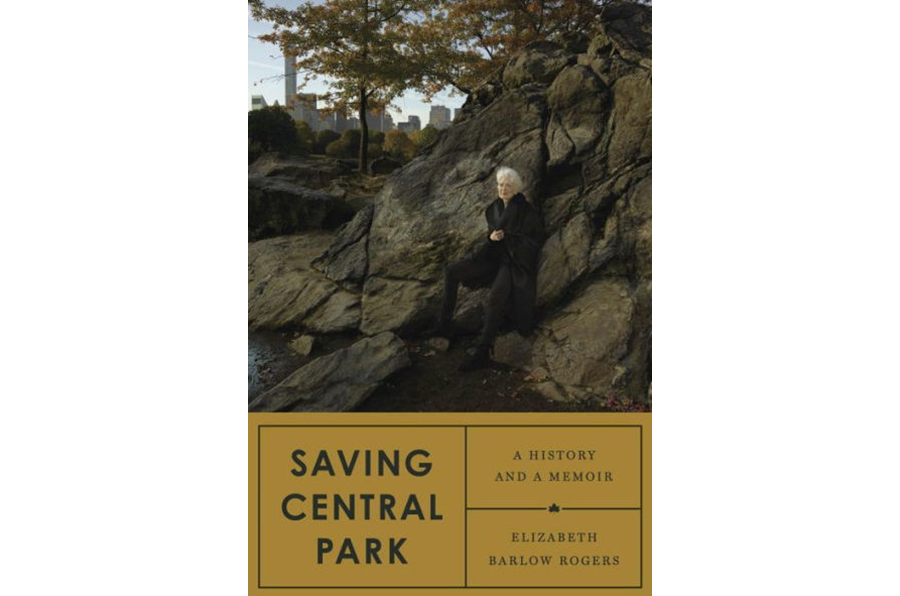

'Saving Central Park' recounts a love affair with a legendary green space

Loading...

An English professor unwittingly made his students even more reluctant to provide him with compositions. He told us our writing enabled him to know each of us intimately.

By a greater order of magnitude, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers freely allows her readers to know her intimately. Ms. Barlow’s new book, Saving Central Park: A History and a Memoir, is a detailed and moving account of her love affair with urban America’s most renowned green place.

At the end of the 1970s Central Park was a post-apocalyptic mess. Far from being a refuge in nature for city people, it famously had become a scary place where headline-making crimes happened. Its lawns had become urban deserts; its woodsy paths eroded, its buildings and other structural elements dramatically vandalized. Barlow writes: “Probably the most glaring symptom of the park’s neglect in 1980 was the estimated fifty thousand square feet of graffiti covering every conceivable hard surface....”

And yet it was all still there, the essence of this 840-acre park, this mammoth manmade project built between 1858 and 1873 following the designs of pioneer landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. And Barlow, along with other visionaries like New York Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis, recognized this.

A watershed event – for Central Park, New York City, and Barlow – happened in 1979 when Davis named Barlow to the office of Central Park Administrator. The next year, he forwarded the creation of the Central Park Conservancy, a public-private partnership Barlow had proposed. Barlow served as Conservancy president until 1996.

At this point, Barlow’s love for Central Park could be fully expressed, along with her “unwavering allegiance to a vision of restoring the park in the spirit of Olmsted and Vaux’s Greensward plan."

Barlow writes, “What Olmsted and Vaux accomplished was an extraordinary feat. They combined complex engineering with naturalistic scenery so skillfully that visitors today are barely aware of the park’s intricate infrastructure."

Today, the rebirth of Central Park, and the Conservancy’s role in this, seems a given. Something had to be done and city government wasn’t doing it. Central Park is now managed and maintained by the Conservancy, which provides most of its budget and 90 percent of its employees.

But the idea of city government ceding responsibility for Central Park to a nonprofit organization struck some people as wrong. There also was the issue of raising many millions of dollars – of necessity relying heavily on wealthy individuals – for restoring countless elements of the park to beauty and soundness and keeping them maintained.

Nonetheless, Barlow and her supporters set to work winning over detractors, wooing contributors, building an organization, and, during the course of her 15 years at the helm, transforming Central Park. The work continues today.

As a memoir, “Saving Central Park” is largely about Barlow, who is an extraordinary and fascinating woman. There’s a lot here about her private life, her public life, and what she thinks, including and especially about Central Park.

It’s clear she doesn’t approve of many of public uses the city has made of Central Park, uses as distasteful to her as marking a museum cafeteria menu in the corner of a Monet painting would be. She shares some unhappy words, for example, about Robert Moses, New York’s “master builder.”

As parks commissioner from 1934 to 1960, Moses greatly altered Central Park to enable and encourage more active public use, often ignoring the Olmsted/Vaux vision. Barlow “deplore[d] Moses’s autocratic manner and ruthless efficiency.” She further comments, “Central Park was not vacant land [freely available for creating new playgrounds, baseball fields, and recreation centers such as Moses built into it] but a landscape with already established forms of recreation and a historic design of signal beauty.”

Barlow’s powerful words – like these – demonstrate that she is not just an astonishingly accomplished and inspired motivator of people who helped create a new paradigm for public-private partnerships. She’s also an accomplished and convincing author. And this book abundantly demonstrates this. Earlier in her professional career, she worked as a writer, and she’s authored other major texts, including books about nature in New York City, about Frederick Law Olmsted, and about landscape design.

Some readers may skip over details she provides of Central Park’s restoration. Nonetheless, most will be inspired by this absorbing self-told story of a life dedicated to recreating a Central Park worthy of its name – this magical-again big green space amidst the crowded blocks of tall buildings in one of the world’s greatest cities.