'Bringing Columbia Home' is a grimly captivating new history of the loss of the space shuttle Columbia

Loading...

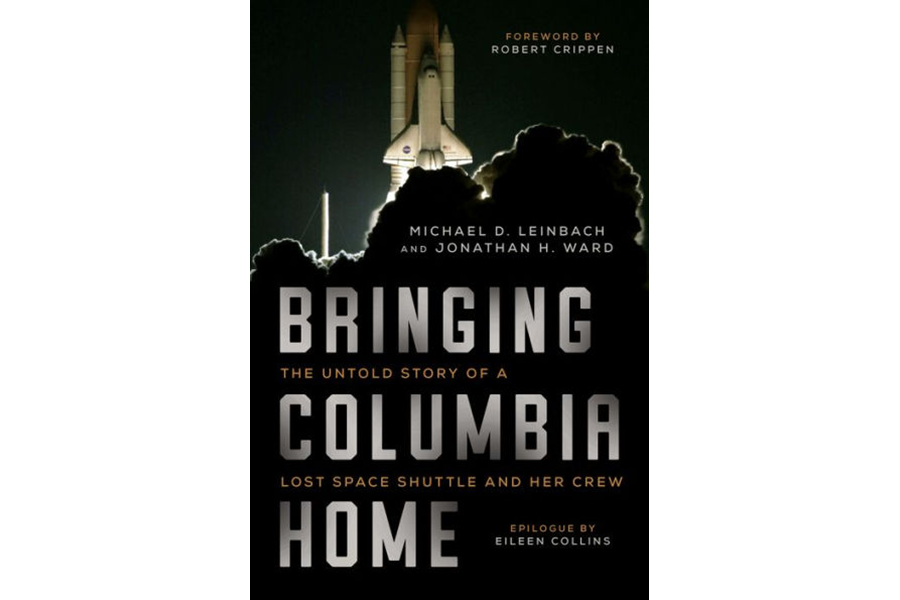

Jonathan Ward has written two previous books on space exploration, and Michael Leinbach was the last launch director for the space shuttle program out of John F. Kennedy Space Center. They've teamed up for Bringing Columbia Home: The Untold Story of a Lost Space Shuttle and Her Crew, a grimly captivating new history of the loss of the space Columbia with all hands on Feb. 1, 2003 and the extended effort to recover the remains of the craft and crew from the many debris locations in Louisiana and East Texas.

In other words, Leinbach and Ward have written the kind of book no lover of space exploration ever wants to write. The title "Bringing Columbia Home" is laced with bitter irony, since in a major sense bringing Columbia home was the one thing all her flight technicians and engineers desperately wanted but failed to do.

Columbia launched on Jan. 16, 2003 with a crew of seven: US Air Force Colonel Rick Husband, the mission commander; Lieutenant Colonel Michael Anderson, the payload commander; Kalpana “KC” Chawla, the flight engineer; and four astronauts on their first shuttle missions: mission specialists Commander Laurel Clark and Captain Dave Brown, mission pilot Commander “Willie” McCool, and Colonel Ilan Ramon, a fighter pilot in the Israeli Air Force, Israel's first astronaut. What everyone considered the eighth crew member was Columbia herself, the oldest shuttle in the American fleet, here on her 28th flight. The more-than-two-week mission was a standard array of experiments, and as Leinbach writes, there was a feeling of business as usual.

“Complacency and past experience lulled us into believing that the shuttle would get her crew home safely – just as she had done more than one hundred times previously – despite the knocks and dings.”

The knocks and dings in question would be the core of the Columbia tragedy. During the launch, a small piece of foam from the gigantic fuel column which was tasked with lifting Columbia into orbit broke off and struck the left wing of the shuttle, dislodging some of the special tiles designed to protect the shuttle from the ferocious heat of re-entry (the shuttle would need to slow down from 16,000 miles per hour in order to taxi to a stop at Cape Canaveral).

Mission control knew from the beginning that this foam-strike could represent a major problem. “If the foam impact we saw had severely damaged the tiles on Columbia's belly or impacted the wing's leading edge, searing hot plasma could enter the vehicle during reentry and melt the ship's internal structure,” our authors write, pointing out that there was no backup to the heat-shield system. “If it was seriously compromised, the crew was not going to make it home.” It had been 17 years since the space shuttle Challenger had exploded moments after takeoff.

Columbia was scheduled to touch down on the morning of Feb. 1, 2003, and a clock was counting down the seconds. When the shuttle failed to appear, NASA quickly realized that its worst fears had come true: The shuttle's heat shielding had failed, and it had been torn apart on re-entry. The crew was dead, and the shuttle program itself would shortly follow them.

“Few words were spoken,” we're told with affecting directness about that morning. “People wept and hugged one another as their initial emptiness slowly filled with grief.”

Leinbach and Ward set their account apart from other Columbia books by following the story from its central tragedy to its almost unthinkably sad immediate aftermath. They detail the painstaking efforts of local, state, and federal law enforcement – and a crowd of hardy, heartbroken volunteers – to do a very melancholy version of the book's title: to bring Columbia and her crew home by combing the woods and marshes of Louisiana and East Texas for every bit of remains, human and machine, that they could find.

The rain of that debris had broken the silence of its rural epicenter. “House windows vibrated so intensely that people feared the glass would shatter. Knickknacks fell from shelves and dressers,” the authors write. “The nonstop booms lasted several minutes, shaking US Forest Service law officer Doug Hamilton's brick house to its foundations."

Despite the dramatic tragedy at the beginning of the book, it's the quiet stories of perseverance and camaraderie that will linger longest with the reader. As subsequent Mars probes have amply demonstrated (and indeed as the Columbia mission itself nearly did; on-board computers controlled nearly ever aspect of the flight), there's little need to risk human lives in space exploration. "Bringing Columbia Home" is mostly a loving tribute to fallen heroes – but it's also a sharp reminder of that risk.