'The Road Not Taken,' a biography of Edward Lansdale, makes no secret of its belief in its hero

Loading...

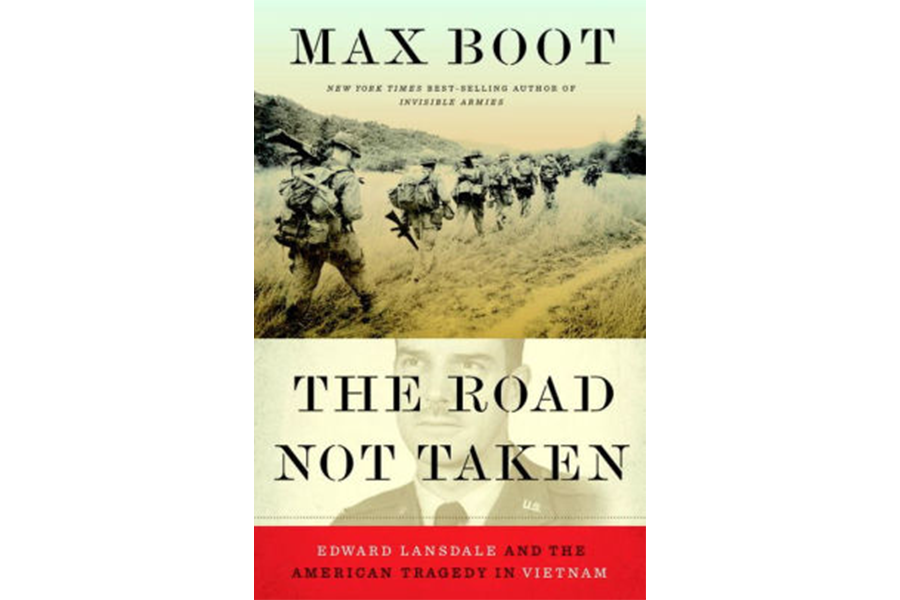

Military theoreticians since Thucydides have alluded to two kinds of warfare: the raw military contest for capturing territory and killing soldiers, and the more subtle business of winning the hearts and minds of the enemy, effectively convincing them to fight your opponent for you. The second kind of warfare had no more vocal champion in the hotbed of mid-20th century brushfire wars than General Edward Lansdale (indeed, he popularized the phrase “hearts and minds” and is still virtually synonymous with it), the subject of The Road Not Taken, a big and contentious new book by Max Boot.

Boot, a Senior Fellow in National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, wrote "Invisible Armies" in 2013, a history of guerrilla warfare, and that subject is key to any study of Lansdale, who left a career in advertising to join the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA, during World War II. In 1950, he was stationed in the Philippines to help the US-backed intelligence services suppress the Hukbalahap uprising against President Quirino. Lansdale, who's described by Boot as “a self-effacing man who favored an informal approach to dealing with the most important questions of war and peace,” became friends with Quirino's Secretary of National Defense, Ramon Magsaysay, and orchestrated his rise to the presidency in 1953.

Starting in 1954, he was stationed in Saigon as head of the Saigon Military Mission where he helped train the Vietnamese National Army and used the psychological-operation “psy-op” methods of mental and emotional manipulation and propaganda he'd perfected in the Philippines in order to strengthen the South's suspicion of the North. He established a friendship with Ngo Dinh Diem, who became the president of South Vietnam in 1955 in an obviously fraudulent referendum in which there were more votes than voters.

In the early 1960s, Lansdale was in charge of Operation Mongoose, a clandestine program dedicated to covertly assassinating Cuban dictator Fidel Castro and undermining the Cuban government. Many of the psy-op tactics he employed there read more like gimmicks from the James Bond novels of Ian Fleming (Lansdale's actual inspiration in some cases) than standard destabilizing procedures. The tactics make for great stories, although obviously Lansdale's work in Cuba was a failure. He retired in 1963, was a kind of roving minister to Vietnam in the late 1960s, wrote a memoir that was pilloried by critics, and died in early 1987. He was given an ornate funeral service involving a black, riderless horse and burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

As even such a cursory summary indicates, Lansdale's career was like an iceberg, with only a small bit of it visible in the clear light of day and the great bulk of it hidden in a morass of acronyms and constantly-shuffling protocols and in-field expeditions conducted entirely “off the books” and free of accountability. This presents a challenge to any biographer, and Boot chooses to answer the challenge by finding in Lansdale a hero, a visionary whose “hearts and minds” approach to exerting American “soft power” abroad, an approach Boot shorthands to three Ls to be applied to any native peoples in a hot-spot: learn, like, and listen. This was a drastic departure from the bludgeoning approach of, for instance, General Westmoreland during the Vietnam War, as Philip Caputo puts it in his memoir "A Rumor of War": “Our missions was not to win terrain or seize positions, but simply to kill: to kill communists and to kill as many of them as possible. Stack 'em like cordwood.”

Lansdale (regularly and disconcertingly referred to by Boot as “Ed” for a good portion of the book) carefully crafted his own legend to portray himself as a champion of the anti-cordwood approach to flexing American muscle: go among the people of foreign countries, learn their thoughts and folklore, sway what Boot refers to as “the all-important X Factor, the feelings of the local populace.”

"The Road Not Taken" is comprehensively researched and insightfully written – Boot is, as always, an extremely talented writer – and it implicitly believes whole-heartedly in that X Factor, and in “Lansdalism” as a foreign policy. Boot made extensive use of previously untapped material provided by Lansdale's family, and perhaps not unconnectedly, his book about Lansdale dismisses even the notion of, for instance, death squads and orchestrated campaigns of terror for terror's sake. When Boot mentions Lansdale using Operation Passage to Freedom as a cover for infiltrating his own cover-warfare teams into North Vietnam, for instance, he grudgingly allows that it “arguably” violated the Geneva Accords. Readers of the Pentagon Papers might come to a less qualified verdict about how dirty Lansdale's hands were in Vietnam and elsewhere.

Boot's book isn't strictly hagiography; he can sometimes be as tough a critic of Lansdale as many of Lansdale's contemporary critics were – the word “delusion” makes more than one appearance. But "The Road Not Taken" makes no secret of its belief in its hero and his faith in the importance of “hearts and minds.”