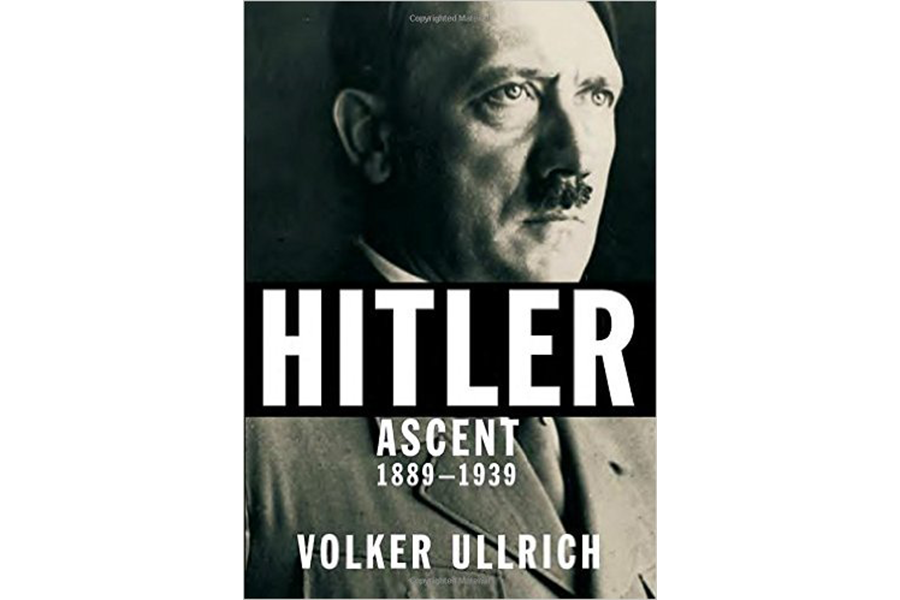

'Hitler: Ascent 1889-1939' is the richest, most convincing portrait yet

Loading...

There is a search implicit in the biography of any monster's youth. In the stations of early life – the parents, the birth, the nursery, the schooling, the adolescence – biographers (and others, in some cases whole nations) study these quotidian details looking for the first deviations, the first signs visible to an impartial onlooker that this person, unlike the dozens of his peers on either side of him, will not grow up normal or sane or morally sound. And the worse the monster, the more thorough, the more strenuous, the search. Hence the ongoing market for studies of Adolf Hitler's early years: how, biographers continuously ask, did he become what he was? When was it earliest apparent that Hitler would become Hitler?

This quest very much animates Hitler: Ascent 1889-1939, Volker Ullrich's enormous biography of Hitler first published in Germany in 2013. Ullrich's book follows the universally praised similar 1998 study by Ian Kershaw, "Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris," and readers who forced themselves to read that book (then, now, and always, Hitler is depressing company) might legitimately wonder how this latest telling of the story even differentiates itself, much less makes itself necessary reading.

Ullrich himself opens his account with just these questions. He writes generously about the great Hitler biographers, from Konrad Heiden to Joachim Fest to Kershaw, and he justifies his own massive endeavor (a second volume will follow "Ascent") on two grounds. The first is the extensive amount of Hitler research that's been done since Kershaw's second volume appeared nearly 20 years ago; the second and more intriguing is the need Ullrich sees to shift the focus more fully onto Hitler the person. “It is a huge mistake,” he contends right at the beginning of his book, “to assume that a criminal on the millennial scale of Hitler must have been a monster.”

The outlines of Hitler's early years are well-known: his birth in 1889 to a modestly middle-class family, his life as a struggling, penniless artist in Vienna, his service in the First World War, where he was wounded, gassed, and decorated, and his eventual entry into politics, joining the movement that would become the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) and thereby finding what Ullrich considers his true calling in life. “His great gift was for politics alone,” Ullrich writes, and he possessed that gift to a far greater extent than the men who thought to control him, men like German President Paul von Hindenburg or former Chancellor Franz von Papen, establishment figures who viewed Hitler as a useful demagogue but not much more. “In his ability to instantaneously analyse and exploit situations,” according to Ullrich, “he was far superior not only to his rivals within the NSDAP but also to the politicians from Germany's mainstream parties.” In a pair of virtuoso chapters, “Month of Destiny: January 1933” and “Totalitarian Revolution,” Ullrich gives readers a very shrewd and insightful account of the precise maneuverings by which Hitler seized power in Germany.

As Ullrich writes, when Hitler declared in December 1922 “We need a strong man, and the National Socialists will produce him,” he was clearly talking about himself, and the heart of "Ascent" – and its most important revelation – is a dissection of how Hitler went about becoming the absolute ruler he is in the book's concluding pages. This is in many ways the most pressing question of the 20th century: How did such naked barbarity as Hitlerism overtake one of the most advanced and cultured nations on Earth in the modern era? How did it come about that the Germany of the 1930s could unleash such murderous chaos on the world, particularly against the Jews of Europe? Ullrich shows it as a tandem process: “Once again it was Hitler who gave the decisive signal for German to give free rein to their hatred and destructive desires.”

Ullrich's Hitler is much more than a simple strong man. Countless anecdotes throughout the book (and its linchpin chapter, “Hitler as Human Being”) serve to paint a more nuanced picture of a man who could be both masterful and debilitatingly insecure, a ranter who could precisely deploy his rants, a savage bully who might also bring flowers to the bedside of a sick employee. Ullrich contends that Hitler was an actor of unerring perception, having perfected the ability to “conceal his personal antipathies behind solicitous gestures.” It's only as power solidifies in his grasp that this chameleon Hitler gradually drops his various smiling guises; as Ullrich's chapters progress, Hitler's various underlings increasingly report their boss withdrawing further and further from normal personal interaction. In the book's closing segments, the familiar crazed dictator of the World War II years is all but fully formed.

The account of that formation in "Hitler: Ascent 1889-1939" is the richest and most convincingly three-dimensional one yet produced by a major biographer. And the fully-human Hitler who emerges from these pages is, inevitably, far more horrifying than a simple monster ever could be.

[Editor's note: The original version of this review misspelled Volker Ullrich's name.]