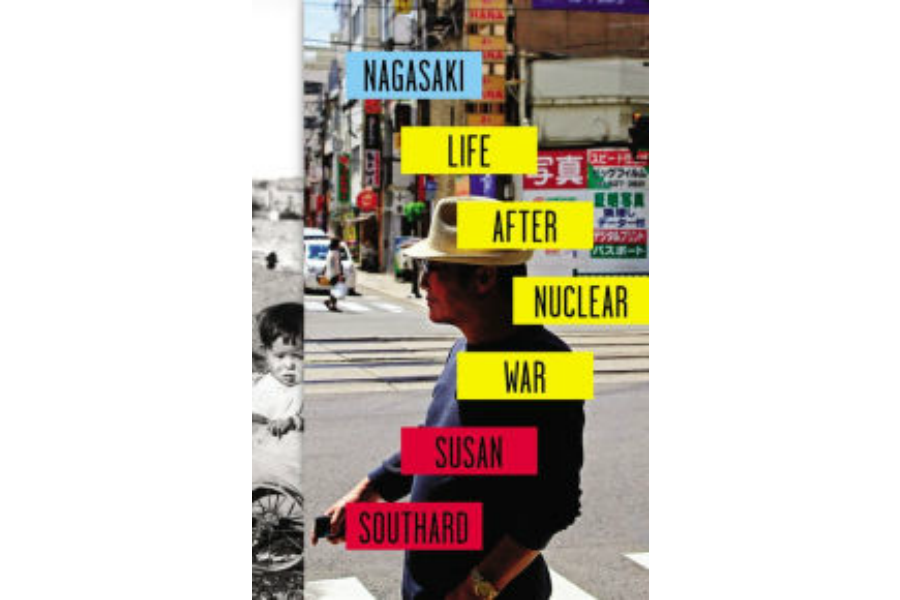

'Nagasaki' is a compelling, unflinching account of life after nuclear war

Loading...

History remembers momentous events exceptionally well but usually takes little note of the second occurrence. To wit: Most Americans can easily name the first pilot to fly across the Atlantic Ocean yet only a few remember that Clarence Chamberlin was the second.

In the same vein, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 is widely regarded as one of the central events of the last century. But the second atomic weapon – employed just three days later on Nagasaki, a port city in Southern Japan – is much less well known.

That may change thanks to Nagasaki, a thoughtful and deeply affecting new book about the bombing of Nagasaki and its aftermath by Susan Southard.

Hoping to bring the war to a conclusion before a planned fall 1945 invasion of the Japanese home islands, the Air Force planned to use the second atomic bomb on Kokura. But poor weather obscured the aiming point and the giant B-29 flown by Major Charles W. Sweeny proceeded to a secondary target and released the weapon over Nagasaki. It exploded at 11:02 am local time at an altitude of about 1,600 feet.

If, as one observer later noted, the seven mile high atomic cloud was “a picture of hell,” the situation on the ground was hell itself. The center city was instantly obliterated. The story Southard recounts in brutal detail is one of suffering, panic, death, and complete destruction. One survivor told of a companion whose “eyeball was hanging out of its socket. His other eye was completely crushed, and his mouth was split open all the way to his ear.” Before long, he was dead.

The blast killed some 40,000 people immediately – less than the number who perished at Hiroshima, but only a fraction of those who would ultimately die. While she makes no effort to provide a definitive count, Southard estimates that more than 70,000 people were dead by the end of 1945 with “countless more” expiring from radiation related illnesses in the years ahead.

She organizes the book around the experiences of five teenage residents who survived: Wada Kōichi, a streetcar operator; two girls, Nagano Etsuko and Dō-oh Mineko, both of whom who worked at a Mitsubishi weapons factory; Taniguchi Sumiteru, a post office employee; and Yoshida Katsuji, a student at the Nagasaki Prefecture Technical School.

All suffered grievous injuries. The available medical treatment was primitive and there were few medical protocols for treating radiation illnesses. In several cases, the treatment lasted for years. Taniguchi Sumiteru, for example, was hospitalized for three years and seven months before being released.

Particularly affecting are the descriptions of the unimaginable challenges the survivors faced. The terribly disfiguring injuries meant that they were ashamed to be seen in public – one stayed “hidden in her house” for several years before gradually venturing out. Making friends and establishing human relationship were virtually impossible. Severe hunger was commonplace. Many “were too weak or too ill to work.” Those well enough to work faced rampant discrimination. Eventually, these individuals became known as “hibakusha” or “explosion affected people.”

Neither the Japanese nor American governments helped very much – the former did not acknowledge the continued suffering of the victims and denied medical assistance claims for years while the later censored accounts of the bombing, claimed that residual radiation was not found at the bomb site, and stifled medical research. In short, neither country treated the grievously injured with much care, dignity, or respect. The victims had to fend for themselves.

Southard’s approach is similar to that of John Hershey’s 1946 best seller "Hiroshima," which told the story of six victims of the first atomic bomb and helped define the way that future generations envisioned the impact of a nuclear war. But while Hershey followed the victims for a single year, Southard tracked them for more than half a century.

The graphic and detailed description of their injuries and suffering makes for a hard, often searing reading experience. This is not a book for the faint of heart.

But remarkably, all of those Southard followed confronted their loss, suffering, and disfigurement and found the grace and courage to lead productive and purposeful lives.

Wada Kōichi, for example, discovered meaning in creating a monument for the more than 100 streetcar employees who died in the bombing. Dō-oh Mineko moved to Tokyo and had a successful career as a cosmetic executive. Taniguchi Sumiteru and Yosida Katsuji became well-known international advocates for efforts to ban war and nuclear weapons. While many hibakusha were routinely rejected as a marriage partners, several of Southard’s subjects enjoyed long and happy marriages. After experiencing alienation and rejection after the bombing, all were admired and respected in old age.

Historians have long debated the need for and wisdom of using the atomic bombs, especially the second. Southard devotes relatively little attention to the military, political, and philosophical issues and focuses instead on consequences for civilians who were caught in the inferno. By doing so, she gives us both a damning indictment of nuclear weapons and an inspiring reminder that some people prevail, even in the face of impossible odds.