'American Cornball' is a funny book about the things people used to laugh at

Loading...

When cultural trivia has ceased to be current but hasn’t yet gotten so old as to be utterly forgotten, it occupies that odd in-between zone we call corny. When I was growing up in the 1980s, the music and clothing of the 1950s was just the right age to be corny, ripe for mockery in shows like "Happy Days" and movies like "Grease"; today, the ’80s themselves are corny, as witness a TV show like "The Goldbergs". The 1950s, in the meantime, have gotten too old for that kind of half-embarrassed, half-affectionate treatment. By now, if you made a movie full of doo-wop and poodle skirts, you wouldn’t be making a joke but a period drama.

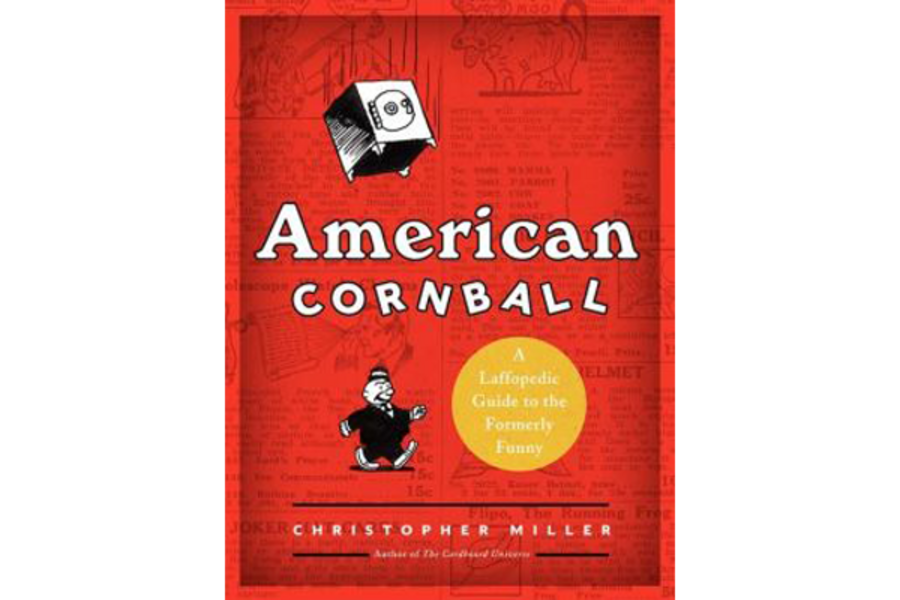

American Cornball, the fascinating and entertaining new book by Christopher Miller, describes itself as a “laffopedic guide to the formerly funny,” and the word “laffopedic” is just the kind of corny old joke it delights in recording. No one says “laffs” anymore; it’s a word out of old comic strips, and anyone who used it today would either be ironically quoting or simply clueless. Miller, however, is an amateur scholar of exactly this kind of obsolete joke – humor that is recent enough to still be recognizable as humor, though it no longer has the power to make us laugh. His subject in "American Cornball" is the comedy of roughly the period 1900 to 1960, in all its forms and media: comic strips, above all, but also novelty gags, Warner Brothers cartoons, funny postcards, radio shows, early sitcoms, and jokes.

Miller guides us through this lost continent of comedy in encyclopedia form, with entries ranging from “Absentminded Professors” and “Alley Cats” through “Limburger” and “Pants” to “Yes-men,” “Yokels,” and “Zealots.” As you read, you start to realize how much of our grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ and even great-great-grandparents’ humor remains familiar, in the way that a dead language can be familiar. Take Limburger cheese, for instance. I’ve never seen it for sale or in a restaurant, and I’ve certainly never eaten it. But because of old cartoons, I know that Limburger was supposed to be the ultimate stinky cheese – which made it, in Miller’s words, “the funny cheese par excellence in the early twentieth century.”

Over the course of a three-page entry, he explains how Limburger showed up in Rube Goldberg gags, early silent films (including one called "Love and Limburger"), "The Three Stooges" (a rich resource for Miller), and finally the Pepe Le Pew cartoons, in which a lady cat who is in love with Pepe smears herself with Limburger in order to match his skunky odor. At the same time, Miller ventures a theory about how Limburger became a comic staple in the first place. We can thank the German immigrants who brought it to America around he year 1900, all of whose customs (such as lederhosen) were ripe for mockery. If no one jokes about Limburger cheese anymore, Miller writes, it’s probably because the descendants of those immigrants stopped eating it, so that today it’s “an endangered species in America.”

Writing about Limburger, Miller sounds like a collector, eager to show off the trivial rarities he has unearthed. And the basis of "American Cornball" is a truly amazing trove of knowledge – it’s hard to imagine that many people can have seen as many old movies or read as many old cartoons. Whether he’s talking about "Krazy Kat" or "I Love Lucy," or the kinds of gag gifts people used to order from the backs of comic books, Miller is able to put his finger on a relevant example. Yet at the same time, he is also an armchair theorist of comedy, full of ideas about why we find certain things funny, and a cultural historian, curious about why our forebears laughed at things that today make us yawn or cringe.

And plenty of old comedy, of course, is cringeworthy. Among the lighthearted subjects in "American Cornball," there are also entries for “Rape,” “Physical Infirmities,” and “Black People” — each of which, Miller shows, our ancestors found endlessly amusing. The racist humor Miller catalogs is shockingly blunt — such as a set of swizzle sticks in the shape of a naked woman, sold under the name “Zulu Lulu.” The rape jokes, on the other hand, are so pervasive that, Miller points out, we often don’t even recognize them as such. No comic icon is as lovable as Harpo Marx, but Harpo is constantly chasing after women, and “what are we to imagine he’d do if he ever caught one in a lonely place? And yet no one thinks of Harpo as primarily – or even secondarily – a would-be rapist,” Miller points out. Viewed from a twenty-first-century perspective, the threat of rape fits all too comfortably into what were seen at the time as unremarkable sexual dynamics – which is what makes these scenes, in retrospect, so disturbing.

At other times, Miller’s interest in comedy is more technical and even literary. His frame of reference often comes from high culture – “There is, as far as I know, not one scene in all of Henry James where a character of either sex sits on a thumbtack,” he observes at the beginning of the entry on “Pain” – and he is interested in the way comic strips, like Petrarchan sonnets, evolved their own rigid conventions. Today, the sight of someone getting hit in the head with a brick would strike us as simply violent; but early comics were what Miller calls “the Golden Age of Imitable Violence,” when “the comics section gave the message that everyone was throwing bricks, and that it was all in good fun.” If you had to throw something in a comic strip, it would be a brick, just as, if you had to drop something, it would be a safe or an anvil. The funniest foods, Miller says, were beans, hash, and soup (all foods associated with poverty); the funniest clothing, pants; the funniest body part, rumps.

And the funniest number, for some reason, was 23, which Miller tracks through an amazing range of appearances – a comic song from 1903, a 1929 gag catalog featuring fake badges bearing the number, a Dr. Seuss book, even Mel Brooks’s "The Producers," where the Nazi would-be playwright lives in Apartment 23. Miller speculates about how 23 might have caught on as the go-to funny number – does it have to do with the phrase “23 skiddoo,” and if so, where does that come from? – but he is not writing as a scholar, and he does not beat the issue to death. Indeed, one of the appealing things about "American Cornball" is its conversational tone, as if Miller were simply, eagerly chatting with you about all the corny things he knows and loves. Browse through this book and you’ll be surprised to discover how many of them you know, too.