I Am the Beggar of the World

Loading...

Landay is a Pashto word, the language spoken by the Pathans. It means a short, poisonous snake. It also means a short, lethal poem. Or a short, bawdy poem – or saucy, rebellious, elegiac, daring, earthy-as-a-truffle poem, though short in any case. A candent poem, flashing, diminutive, and sharp: a couplet with a total of 22 syllables; the first line of nine, the second of 13. Landays are found in the borderlands spanning Afghanistan and Pakistan, created (mostly) by and for women, in a region where women are rarely behind the wheel. Traditionally, the landay is a distillation of love, grief, homeland, separation, or war, so there is poignancy. But there is laughter, too, laughter as a survival skill as important as building fire or shelter.

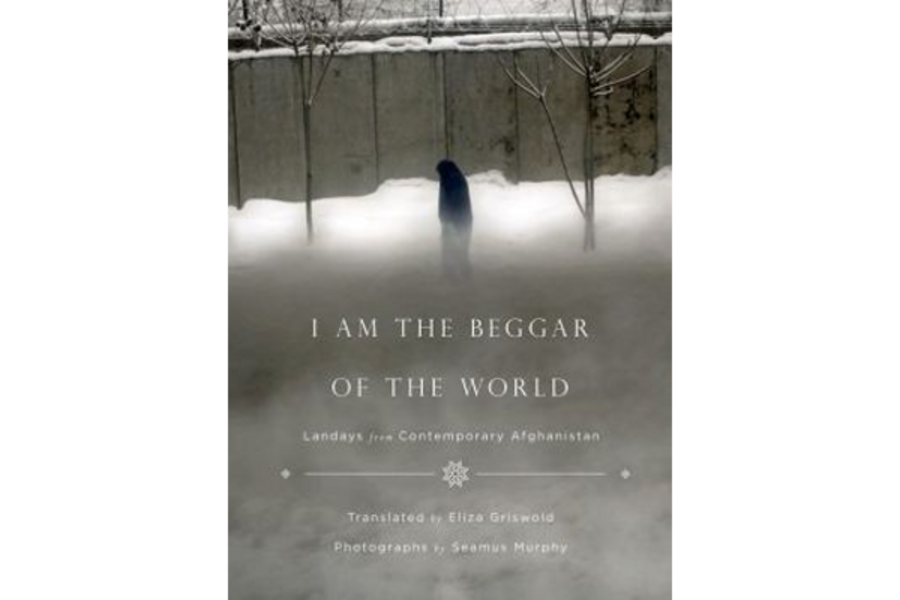

I Am the Beggar of the World is a gathering of landays from today's Afghanistan – both hoary and spanking new, some tinkered with, others morphed by the changing world – translated by the journalist/poet Eliza Griswold, accompanied by photographs by Seamus Murphy. A word about the photographs: They are not only transporting, they are atmospheric disturbances – breathtaking in their contemporaneity – independent of the poems and text but feeding off one another.

"I Am the Beggar of the World" was not easy task to realize. Griswold was first drawn to the landays when one young woman – who was part of a Kabul-based writers' circle but lived far away and communicated secretly by telephone and who had been writing landays – self-immolated when confronted with a marriage she could not abide. Griswold learned the woman's village and decided that if she was going to write about the woman with veracity, she had to go there and experience it for herself.

That was dangerous. Kabul, the country's capital, is one world; the provinces, where 80 percent of Afghan women live, altogether another. Afghanistan is a loose – very loose – confederation of regions: village-states, valley-states, which can be tough customers, where some consider a splash of acid to the face as an appropriate rebuke for teenage girls with the temerity to speak of literacy as a valuable resource, let alone a right. Griswold, being a woman and an American, was not exactly an unbeatable combination. To find the landays required hard travel to distant places – the norm when looking for precious stones: "into camps of startled nomads, rural backyards to private homes, a muddy one-horse farm, a stark refugee wedding, and a glitzy one in a neon-lit Kabul hall." And secretly; when not secretly, then very quietly.

Landays are typically sung, and today singing is linked to licentiousness in the Afghan consciousness. Women singers are viewed as prostitutes. But the singing goes on: "Usually in a village or a family one woman is more skilled than the others at singing landays, yet men have no idea who she is. Much of an Afghan woman's life involves a cloak-and-dagger dance around honor – a gap between who she seems and who she is."

The landays are anonymous, clandestine but with feet to get around, and collective; they protect the composer. They are a look through the keyhole into a sensorium, a way of seeing and being. They are a play on the silence of women in a man's world. For all their folk origins, they are world wise, and sensuous in their brevity, the bareness of things being what they are, sometimes caustic, sometime gay balloons, made delirious by the helium in their words.

Translating the landays was an intricate process, roughed out over gallons of green tea, "word by word into sometimes nonsensical English," literal versions that Griswold reworked with native Pashto speakers. "My versions rhyme more often than the originals do because the English folk tradition of rhyme proved the most effective way of representing in English the lilt of Pashto." Intricate and fascinating.

In an article Griswold wrote for The New York Times Magazine, a springboard for the book, one landay is translated, "Making love to an old man is like / Making love to a limp cornstalk blackened by fungus." By the time it made it in "Beggar of the World," it read, "Making love to an old man / is like fucking a shriveled cornstalk black with mold." The wonders of the pickling process. "Sex, marriage, love – all can be the same thing, so a literal rendering of this poem goes something like this: Love or Sex or Marriage, Man, Old / Love or Sex or Marriage, Cornstalk, Black Fungal Blight. In other words, mystifying."

But Griswold's end products here have been vetted enough to yield magic out of mystery. On sex, there are rough exhortations and the mocking of weakness: "Is there not one man brave enough to see / how my untouched thighs burn the trousers off me?" Or, "You'll understand why I wear bangles / when you choose the wrong bed in the dark and mine jangle." In a pique of jealousy "God, turn my lover into a fox / and make my rival a chicken." (Griswold provides annotations to help guide you through the more brambly associations.)

There are the shape-shifters, where a "common joke is that the Internet has replaced the riverbank as a prime spot for wooing." Grief: "In my dream, I am the president. / When I awake, I am the beggar of the world." And hypocrisy: "You'll never be a mullah, talib, no matter what you do. / Studying in your book, you see my green tattoo."

There is no room for slackers – "Be black with gunpowder or be bloodied / but don't come home whole and disgrace my bed" echoes the Roman exhortation with-your-shield-or-on-it – while sadness is like an occupying army: "My love gave his life for our homeland. / I'll sew his shroud with a strand of my hair." They speak to war, invaders, and interlopers of many stripes – British, Russian, and American – while invoking an elemental heartache, fragile, impermanent, swift, and wrapped in a winding sheet.

Landays speak of something else elemental: the life of the mind and the heart that goes on under the cover of the chadri. These verses testify not only to the existence of Afghan women, but to their shrewd instincts, deep emotions, their dignity and humanity.