The uncompromising life and legacy of activist Sylvia Pankhurst

Loading...

The British population numbered more than 40 million people in 1900, but only about 6 million of those were allowed to vote. There were age and property restrictions, but the biggest excluding factor was that no woman was permitted to cast a ballot. Many women, and some men, devoted themselves tirelessly to the protracted struggle for women’s suffrage. But it was not until 1928 that all women over the age of 21 were enfranchised. Arguably, few suffered as much to achieve that victory than Sylvia Pankhurst.

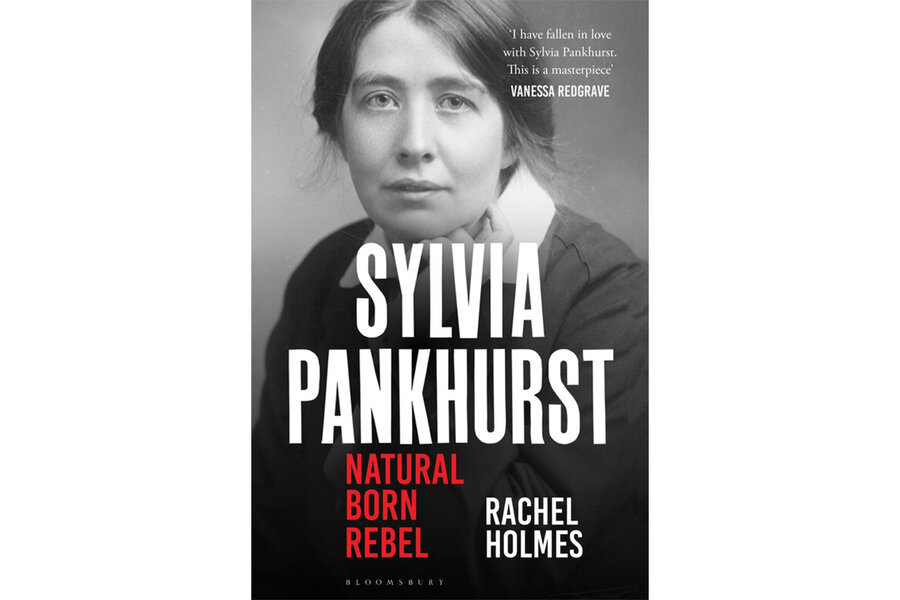

Cultural historian Rachel Holmes describes Pankhurst’s all-consuming activism – which resulted in multiple imprisonments, during which she endured brutal forced feedings – in her excellent and admiring new biography, “Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel.” But while the activist is best remembered for her work in the fight for suffrage, that was only one act of her long, extraordinary life. She was a talented painter and prolific writer. In addition, she threw herself into revolutionary politics, becoming a passionate anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-colonialist.

It’s unsurprising, though, that Pankhurst is most associated with the suffrage fight. She demonstrated astonishing courage in protesting for the vote. She’d been raised to do so, after all. Pankhurst was born in 1882 to a storied activist family whose home bustled with visits from assorted radicals, socialists, and anarchists. Her father Richard, a lawyer who was both a socialist and a feminist, used to tell his children, “If you do not grow up to help other people you will not have been worth the upbringing!”

Pankhurst’s mother Emmeline, described by Holmes as "England’s most famous suffragette,” founded the militant Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903 – an event that would direct the course of her daughter’s life. At the time, Pankhurst had been pursuing a career in art; she felt torn between her desire to make a living as a painter and her obligations to the suffrage campaign. Her imperious mother clarified her priorities. In Holmes’ words, Pankhurst “expected to do her duty to the movement, regardless of whether or not she could eat or pay her rent.”

In the end, Pankhurst largely set her art aside to fight for the vote in the decade leading up to World War I. It was a period characterized by mass protest in England; most demonstrations were met with an oppressive police response. She was imprisoned in London 13 times in 1913 and 1914, harrowing experiences that made her “as committed to prison reform as she was to the women’s vote,” Holmes writes.

The prison conditions led her, along with many fellow detainees, to engage in hunger strikes. The government responded by force-feeding the strikers, and Pankhurst, who, Holmes writes, evinced a “terrifying capacity for martyrdom,” eventually received more feedings than any other prisoner, resulting in adverse health effects throughout her life. Holmes’s detailed descriptions of the violent procedure, widely considered to be torture, make for difficult reading. Pankhurst was aware of this as well: She wrote powerful accounts of her experiences that helped sway public opinion in favor of the prisoners.

During this time Pankhurst broke with her mother and her sister Christabel, who together ran the WSPU. The rift was ideological, as Pankhurst alone of the three wanted to link the struggles of women to the struggles of the working class. They also disagreed on tactics: Pankhurst accepted public acts of militancy like communal window-smashing but opposed covert acts of arson and property destruction that her mother and sister embraced.

They never reconciled. Pankhurst, who, in the author’s words, often lamented the wasted potential of women “whose lives were constrained by marriage, maternity, and convention,” never married. She had a 10-year affair with British Labour Party leader Keir Hardie, the country’s first socialist member of parliament and a family friend she’d known since childhood. She later had a decades-long relationship with exiled Italian anarchist Silvio Corio, with whom she had a son, Richard, her only child, when she was 45. The out-of-wedlock pregnancy finalized the painful break with Emmeline, who refused to see Sylvia and died months after her grandson was born.

To capture Pankhurst’s life, Holmes plumbs her subject’s published writings and private correspondence, while also benefiting from the work of other historians and access to newly available archival material. The book is long – nearly 1,000 pages – and Holmes can’t resist devoting extended passages to various interesting agitators who come in and out of Pankhurst’s life. But her command of the material, which covers not only suffrage but Pankhurst’s involvement in everything from anti-war protest to political turmoil in Russia, India, and Ethiopia (Pankhurst led international protests when fascist Italy invaded the African kingdom), is impressive. The author vividly portrays both the sweep of events and her subject’s inner conflicts. Indeed, Holmes excels in showing how Pankhurst's mental turmoil both shaped and drove her, leading to a remarkably forward-thinking understanding of the connections between gender, class, and race.

Pankhurst spent the last four years of her life in Ethiopia, at the invitation of Emperor Haile Selassie, who had become a friend. Upon her death in 1960, she received an elaborate state funeral there.

She once said she hoped to be remembered “as a citizen of the world,” and being one, Holmes observes, “required the constant taking of sides.” Pankhurst took sides until the very end.