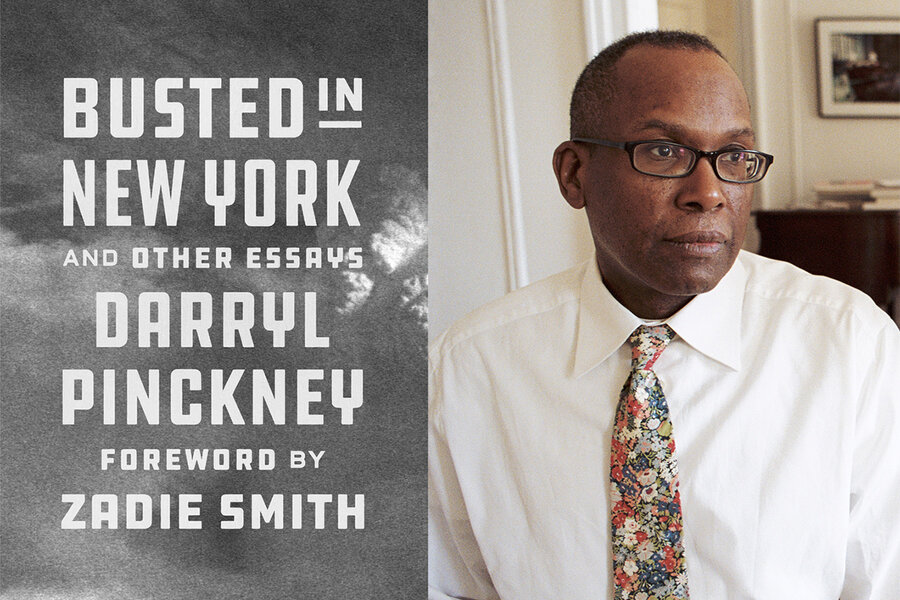

Q&A with Darryl Pinckney: The paradox of black visibility

Loading...

Darryl Pinckney’s latest literary compilation places a historical lens on the most pivotal moments in black America. From his examination of race relations during Barack Obama’s presidency to his nuanced analysis of the Black Lives Matter movement, Mr. Pinckney’s vast knowledge and critical dexterity make him one of the most vital intellectuals of our time. He spoke recently with Monitor correspondent Candace McDuffie.

In the book, you discuss the notion of invisibility. Do you ever think that black people oscillate between invisibility and hypervisibility?

It’s a very strange and paradoxical situation because of course, in the culture itself, black people are very visible. It’s not that we’re merely invisible or even hypervisible – it’s that we’re confined, and then [we’re] troubling when we break out of these confinements, whether it’s physical or psychological. There’s always something about us that has to be “coped with.” I also don’t think hypervisibility is a fair term; I come from a generation that feels visibility has its own importance because it demonstrates that it’s possible.

Why We Wrote This

As black culture moves mainstream, questions of ownership and visibility surface. In a Q&A on these themes, African American writer Darryl Pinckney argues that America’s enduring racism has to do with fear.

You tackle “Afro-pessimism” – the deliberate withdrawal of political and social consciousness by black people – in your book. Do you think it’s a coping tool?

Afro-pessimism can be described as an immediate verdict on American institutions, American systems, American history. It is a very fierce kind of judgment as well as a kind of armor: “I cannot be hurt. I can’t be disappointed.” It’s one thing to understand the mood of Afro-pessimism, but you have to put it in a larger context. It’s about how different the world is. In this era of climate change and underlying anxiety about resources, people are uneasy because certain traditional reliances are not there and democracy is slipping away. There needs to be a category that fits with the sense that all’s not right with the world – let’s not fool ourselves.

But why is this attitude so endemic in the black experience?

It’s a deep thing and it has its roots in how black people have felt excluded, exploited, and oppressed not just in relation to the U.S. but the West in general. There were civil rights movements for the past century that went with ideas of growth, development, transformational possibilities, a general sense that society moves forward by the measures of advancement – but that’s pretty much gone. If you think about it, late [James] Baldwin is a kind of Afro-pessimism where he’s sort of “the scales have fallen from my eyes.” But Afro-pessimism is a bit like passing [as white] – it solves your problem but it doesn’t solve the problems of black people.

What do you think about white authors writing about black culture?

There are so many voices that I wouldn’t be in favor of denying or stifling any of them – especially because I do know some white writers who know a lot about certain black things as anthropologists, musicologists, and historians. It’s also a feature of black culture; Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes were really frustrated that white writers could use black folks’ material and get their plays produced or their novels published while they struggled with the same material. They felt like [their culture] was being taken away.

But isn’t that still a valid concern?

We are getting past this utilitarian view of black culture, which is part of the pain of it entering the mainstream. The sense that we’re losing it, or its purity is at risk, or it’s going to be misunderstood, or people who have no business talking about it are going to start talking about it. There are two things going on: One is an ownership question and the other is a freedom of creativity question and the two can’t really be reconciled. A hundred years ago, slave narratives were not admitted or valued as historical evidence because they were biased. Accounting for bias, overcoming bias, or explaining it is the duty of the writing itself. There is good writing and bad writing; I would look for the good writers and not care about the ones who are bad. Bad writing has a falseness to it.

Despite all of our struggles and our advocacy and our resistance, black people are constantly stereotyped and subjected to racism. Why is this still happening?

It’s black anger people are still frightened of. Even Obama did that thing of tamping down the anger. But there’s bound to be more of it – I mean look where we’re headed. I think that ... people are afraid even after a black president. White people have always divided black people into two categories: black people they’re afraid of and black people they’re not. There’s the insult of that underneath it all. I’m tired of it, too, and there is no time off from it. But I don’t think I’d want to experience life on their side ... not at all. It’s an easy thing to say and a hard thing to explain.