Sotloff murder sparks outrage and condemnation, but should it drive policy?

Loading...

A man with a British accent, hiding behind a mask, threatens his audience as he waves his knife around over the bound and defenseless hostage. The murderer is practically preening as he runs through his exhortations. In his mind, he's elevated himself to the level of the world's great powers. And then he beheads his victim.

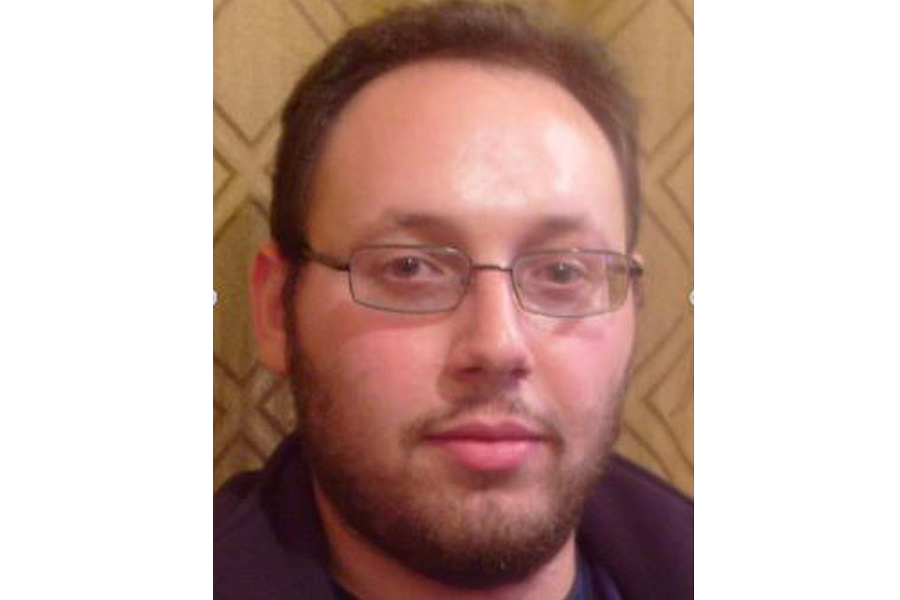

That's what happened when US journalist James Foley was murdered two weeks ago. And now it's the turn of Steven Sotloff, likely at the hands of the same murderer. In both cases, the video was designed to shock and frighten in service of the self-styled "Islamic State," a jihadi group based in Iraq and Syria.

Mr. Foley's murder led to a surge in statements from the White House and Congress about the urgent need to confront the group, and Mr. Sotloff's killing will probably add fuel to US concern. Both stories have dominated television news the way few tales out of Syria ever do.

But is it wise to play into the propaganda strategy of ISIS? Shock, fear, outrage, and perhaps recruiting are what the killer and his friends are after. And while it's good to devote resources to combating the group, two murdered Americans do nothing to simplify the situation in Iraq or Syria.

And consider how much more attention these murders get than, say, the 600 Iraqi captives that IS murdered in June after overrunning Tikrit. Human Rights Watch reports that the group carried out a series of mass executions, mostly of captured Iraqi soldiers, at Saddam Hussein's old palace complex overlooking the Tigris.

Since 2011, nearly 200,000 people have been killed in Syria's raging, multi-front civil war. Civilians have been killed by the Syrian Army and by rebel factions, which are both fighting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and each other. The factions include Al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, which is distinct from the Islamic State.

For the past two years, President Obama's policy has been that Mr. Assad, who is backed by Iran and supplied by Russia, "must go," somehow. But the Sunni jihadis of groups like IS and Nusra, the US has come to realize, wouldn't be much of an improvement. Syria's Sunni Muslims appear to fear them, and may prefer to stick with Assad's regime. Moreover, a victory for Sunni extremists would be an absolute catastrophe for minority Christians and Alawites, since IS is determined to wipe those and all other faiths from the planet.

Yet in Iraq, where the US has been helping the central government and the country's Kurdish minority fight IS, the White House finds itself allied with Iran, which also wants Baghdad to repel IS. However, Iran's objective is to ensure long-term Shiite hegemony in Iraq, while the US sees the highly sectarian policies of Iraq's Shiite-dominated government are driving Sunnis to take up arms and side with IS.

The situation is, in other words, a terrible mess. And reacting emotionally when tragedies occur, or insisting that the US return to war on multiple fronts in the Middle East, is a sure way to lead to error. People are frustrated that Obama admits he doesn't have a clear "strategy" for the religious, ethnic civil wars of Iraq and Syria? Well, demanding war in knee-jerk fashion isn't a strategy.

On March 31, 2004, a group of four American security contractors guarding a convoy of supplies for the US military were ambushed and killed by insurgents near Fallujah, their bodies dragged through the local streets and hung from a bridge over the Euphrates. The pictures spread on the Internet and the US outrage was intense. Given the presence of US troops occupying the country, the analogy with Syria isn't exact, but the response is worth recalling.

US commanders at the time responded from a place of emotion, insisting that Fallujah must be brought under control. Within four days 2,500 US soldiers, mostly Marines, had surrounded the town. The intense battle that ensued killed many insurgents – but also about 600 Iraqi civilians, and at the cost of 50 American lives.

What did the emotionally driven US response gain the country strategically? As I wrote from Baghdad in the middle of April that year:

Iraqi leaders and foreign analysts say the fighting in Fallujah, which has claimed around 700 Iraqi lives, has turned the muddled center of Iraqi public opinion - where people were ambivalent about the occupation but not actively opposed - decisively against the US-led Coalition Provisional Authority and its local allies.

"Fallujah has created a major polarization of Iraqi public opinion. There is no middle ground any more,'' says an adviser to the CPA. "Two weeks ago Iraqis wanted to see us make promises and deliver on them - rebuild, improve - but then they saw pictures of US bombs falling on a mosque in Fallujah. Now they want us out."

There were also other consequences, including a second, bloodier battle over Fallujah at the end of 2004. Tales of Al Qaeda in Iraq – the predecessor of the jihadi group that murdered Mr. Sotloff – going toe to toe with US troops spread around the Internet. This defiance helped the group to attract a second wave of foreign jihadi wannabes. The Al Qaeda in Iraq members who survived also gained important war-fighting experience. Many of those militants who are still active are now fighting with IS.