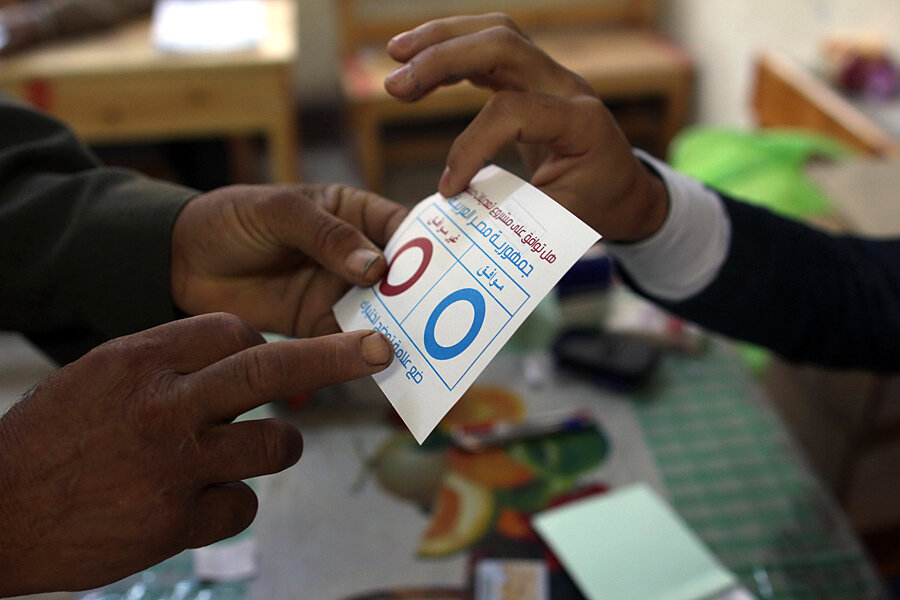

Egypt's constitutional referendum: It's not about democracy any more.

Loading...

The referendum on Egypt's new constitution is wrapping up, its passage a foregone conclusion. The interim military government and its backers have fostered a martial, nationalistic climate around the vote with a simple message: A "yes" vote is a vote for Egypt; a "no" vote is a vote for terrorism and chaos.

By any standard, the vote today is the least free and fair of the five national referendums and elections held since Egypt's military-backed dictator Hosni Mubarak was pushed from power by mass protests in February 2011. The new constitution won't change the principal issues that led to the uprising – rampant police brutality with no accountability, a sclerotic and corrupt economy dominated by the cronies of those in power – and it appears to pave the way for a restoration of the old manner of government that prevailed before the protests against Mubarak broke out.

Is this is a complete disaster? Well, if you believe that democracy is the answer to all a society's ills, then yes. Gen. Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, who leads Egypt's interim military government, is now in pole position to win Egypt's presidency and he's not that different from Mr. Mubarak.

But it also can't be ignored that what's going on in Egypt right now is very popular among Egyptians. How popular is difficult to say – but the mass protests that broke out last June against Egypt's first democratically-elected president, Mohamed Morsi, creating the conditions for the military's takeover, were by most accounts even larger than the ones that helped sweep Mubarak from power.

The Egyptian military really is wildly popular within Egyptian society, and fear that Mr. Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood would forcibly Islamicize Egyptian society if left in power is real.

This is the paradox of Egyptian politics at the moment. The country is moving further away from democracy and vast numbers of Egyptians, perhaps even a majority, seem OK with it. The room for political dissent that existed in the aftermath of Mubarak's fall has steadily narrowed, and now Egypt is about as free or unfree as it was before Jan. 25, 2011, when protests broke out. Hundreds of political prisoners are in Egypt's jails, police corruption and brutality (which provided the initial spark for the uprising) are as bad as ever, and a climate of fear has returned.

The constitution isn't really that important, though from the perspective of basic rights it seems to be an improvement over the previous document, which had far more democratic legitimacy. This one curtails the role of Islam in legislation, promises equal social and political rights for men and woman, provides more latitude for freedom of speech, and bans discrimination based on religion or belief. (Evan Hill has a nice rundown on the differences between this constitution and the 2012 version.) Like the document from 2012, it retains the military's autonomous powers – including the power to try civilians in military courts.

But the words in a constitution are usually far less important than a country's political constitution, and many constitutions that looks good on paper (the current Iraqi one comes to mind) are often simply ignored when they get in leaders' way. Is Egypt about to become a paradise for the rights of women or its Christian minorities because the constitution says so? Will the journalists currently in detention be sprung from the jails after the referendum? Almost certainly not.

None of this can sweep away the grim turn Egypt's so-called "spring" has taken.

Egyptian police have arrested citizens for the crime of campaigning for a "no" vote on the constitution, political paranoia led to the investigation of a satirical television puppet on charges it supports terrorism, and even a hint of sedition can lead to being thrown in jail. Consider this piece by Max Rodenbeck, where he points out that an Egyptian man's home has been raided multiple times by the police and he now sleeps in the olive groves around his village. Why? A car that looks much like his own was captured in a photograph of a pro-Muslim Brotherhood mob burning down a local police station a few months ago. Rodenbeck writes:

Apparently unconvinced by protests from his family that Mr Y has never had anything to do with the Brothers, officers of the law keep barging into his house. For his own safety Mr Y has given up driving his taxi. He sleeps in the dense olive groves surrounding the village, only occasionally slipping home. He says he would like to give himself up and prove his innocence, but fears he will be dragged off to prison.That is what has happened to several other alleged Muslim Brothers in the village, while the former local Brotherhood MP has fled to Sudan. Not knowing what else to do, Mr Y’s family has put up signs affirming that they, too, will proudly vote YES.

Many Egyptians came to believe that straight-up democracy was destined to empower the Muslim Brotherhood, the country's most focused and organized political group, and have supported efforts to prevent that from happening. Since the military came to power the Brotherhood has been outlawed as a terrorist group (despite having publicly disavowed using political violence to achieve its goals decades ago). The chance of fair and open competition in the political sphere any time soon is next to none.

Will Egypt be willing to live with that? It certainly seems so for now - though the country's dire economic state and millions living on just a few dollars a day could end up changing that position, again.

A constitution isn't going to fix Egypt's myriad problems. Whether the country's incoming leaders, with the certain-to-be large influence of the military, will be able to remains to be seen. (For a flavor of the Army worship that's broken out of late, look at the video at the bottom of this post).

If recent history is anything to go by, the outlook is not good.