After centuries of cultural theft, why more nations are returning looted artifacts

Loading...

In June 2013, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned to Cambodia two 10th-century sandstone statues, originally looted in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge.

In July 2017, craft company Hobby Lobby returned to Iraq 5,500 artifacts, including ancient cuneiform clay tablets, illegally smuggled out of the country in 2009 and camouflaged as tiles.

In October 2017, France returned to Egypt eight 3,000-year-old statuettes illegally smuggled out of the country and seized by French authorities at a Paris train station.

After centuries of cultural theft, the pendulum may be swinging toward repatriation.

It’s a trend that has accelerated over the past decade, thanks to increased awareness of past cultural injustices and renewed respect for national sovereignty, some experts say.

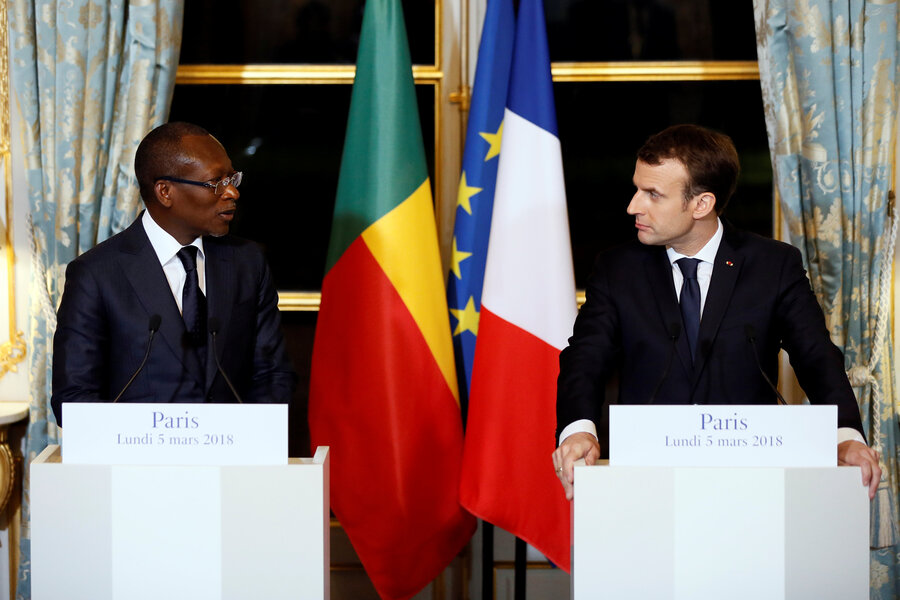

On March 5, France, home to thousands of plundered artifacts in museums and private collections, added fresh momentum to the trend.

In a joint appearance with President Patrice Talon of Benin, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the appointment of two experts to craft plans for the return of African artifacts held in French museums, echoing a November speech in which he said, “African heritage cannot be a prisoner of European museums.”

His bold pledge to return African artifacts in the next five years – and the overwhelmingly positive reaction to it – may be evidence of a generational shift in attitudes on repatriation, says Elizabeth Campbell, director of the Center for Art Collection Ethics at the University of Denver in Colorado. “[Repatriation] provides a sense of belated justice for past human rights and cultural abuses,” she says. “It’s more than a legal matter of who has clear title; it’s a moral issue.”

This growing awareness “has made the topic of return and restitution one of the main concerns of this age and a priority for UNESCO’s member states,” says Edouard Planche, a heritage specialist with the organization.

In 1970, UNESCO created a treaty designed to curb the transfer of stolen cultural goods. As a result, many museums will now display pieces purchased before 1970 and return objects acquired after. Since the convention, a number of national and international databases to track stolen art and artifacts have also been created, including an INTERPOL database, the Lost Art Database, and the National Stolen Art File.

Data on global repatriation is scarce, but progress is evident. Since 2007, the United States has returned more than 8,000 stolen artifacts to 30 countries, including paintings from Poland, manuscripts from Peru, and dinosaur fossils from Mongolia, according to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Of course, the trend extends beyond US borders. In January, Venezuela returned to Costa Rica 196 pre-Columbian artifacts; in January 2016, Canada returned to Bulgaria an antique Cretan sword and dagger; and in July 2015, Canada returned to Lebanon an ancient Phoenician pendant dating back to 600 BC.

And while the artifacts are cultural treasures, the symbolism is often as important, adds Julia Fischer, a professor of art history at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas. “Getting these objects back would be a symbolic win for [the countries] and proclaim that they are no longer victims of colonialism but are independent nations.”

Of course, challenges – and critics – are plentiful.

A United Nations report issued in 2012 evaluating the effectiveness of the 1970 convention found it to have “serious weaknesses,” including a lack of staffing, resources, and laws to back it up.

The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the rise of Islamic State in Syria and Iraq “ushered in a new period of illicit trafficking of objects from the Middle East,” says Professor Campbell. In response, the UN in February 2015 approved a resolution calling for countries to take steps to prevent trade of stolen Iraqi and Syrian property.

And the debate on repatriation is by no means settled, with some critics questioning whether countries of origin necessarily have the resources for proper care and preservation.

For many of the people to whom these artifacts arguably belong, however, the debate is moot.

“As Iraqis, these monuments mean a lot to us,” says Yazan Fadhli, an Iraqi who worked as a linguist for the US during the most recent conflict. After years of unrest in Iraq, “It’s something that helps us forget what divides us ... and gives us hope and confidence and motivation to build back our country again.”