Why hackers are so obsessed with picking locks

Loading...

| New York City

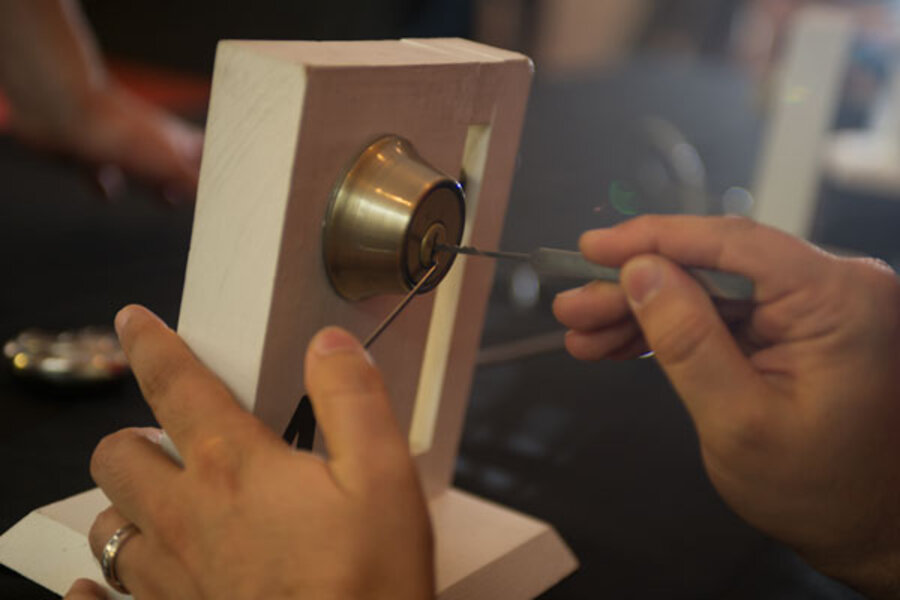

At a recent computer security conference here, Ash Riley attempted to hack something that didn't contain any code or circuitry: a lock.

The college student from Westchester, N.Y., worked at it for 15 minutes, patiently trying a metal pick to move the lock's internal pins. As she was about to give up, Ms. Riley angled her tool just the right direction and the lock opened.

"I did it, I did it!" Riley told her boyfriend, Adil Sadik, who also picked his first lock the day before. "It was so exciting."

So-called "lock-picking villages" like the one that Riley and Mr. Sadik visited at the Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) cybersecurity conference in July have become mainstays at cybersecurity conferences and college coding competitions.

In many ways, physical locking picking gets to the heart of what it means to be a computer hacker, say cybersecurity experts and lock-picking enthusiasts. They say it mimics what hackers do in the virtual world – working to figure out vulnerabilities in systems with the goal of patching flaws and improving overall security.

"It's the only way you're going to understand something, is if you pick it apart and look at the insides," said Eric Gordon Corley, the founder of HOPE and publisher of the hacker magazine 2600. “Everything else is in a black box, and that's not healthy.”

After seeing a lock-picking village at a German hacker conference more than a decade ago, Mr. Corley invited members of The Open Organization Of Lockpickers (TOOOL), a nonprofit dedicated to publicizing information about locks and (legal) lock picking, to stage a similar event at his New York conference in 2004. Within a few years, TOOOL branched out into the US and lock-picking villages began springing up at tech gatherings across the country.

"Almost invariably, on someone's very first time learning, awe is the reaction — awe at how easily they can do something that most people think they can't do,” said a hacker known as Deviant Ollam, a TOOOL board member.

Now, the US chapter of TOOOL runs most of the lock-picking villages at hacker and cybersecurity gatherings in the US. At the recent DEF CON security conference in Las Vegas, the group ran a “teaching village” where attendees could receive basic lock-picking instructions. More advanced pickers competed in a timed lock-picking competition.

The goal, says Ollam, is to "learn as much as you can about how something works, stress and push at the edges of the system to make it work the way it wasn't suppose to work and then experiment and see what unexpected things you can make it do — that's the same mantra, the same ethos, whether you're talking about ones and zeros or little pieces of metal."

Ollam says TOOOL has two cardinal rules that it lays out at the beginning of every training session: Don’t pick a lock you don’t have permission to pick, and don’t pick a lock you rely on (in case you break it).

Still, as is often the case with computer hacking, lock picking has an edgy allure. It's all about learning to beat systems that are designed to keep people out.

"That's definitely, definitely one of the reasons that keeps hackers engaging in that sort of activity," says Gabriella Coleman, an anthropologist at McGill University who studies hacker culture. "Then, of course, doing it in the context of hacker cons and stuff like that reminds people that you should be responsible."

The basics of lock picking are fairly simple.

Picking the most common type of lock, called a pin-and-tumbler, requires two tools: A pick and a turning tool. The turning tool keeps constant, gentle pressure on the lock so that it will turn once the pins are in place. The pick feels for when each pin catches in place, like the teeth on a key. With minimal instruction, most people can pick a simple one- or two-pin lock in minutes. But the intricacies of locks and lock picking can take years to master.

To be sure, lock picking has been a hacker pastime for decades. In 1987, the pseudonymous Ted the Tool authored "The MIT Guide to Lock picking" — a how-to manual named for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where students have long been rumored to use lock picking in their famous campus pranks.

But as the hobby spreads, newcomers seem to get the message that longtime lock-picking adherents are trying to convey: in order to fix something, you first need to know how to break it.

"Especially in computers, you can't really see or feel what's going on," said Sadik, who attended HOPE with his girlfriend and works in technology. “It's cool to be able to do that with a lock, which is a system that's designed to secure something but may still be broken into."