Where is Trump getting his cybersecurity advice?

Loading...

Amid the growing controversy over intelligence reports that Russian hackers meddled in US elections to aid Donald Trump's campaign, it's unclear who the president-elect is listening to on matters of cybersecurity right now.

Even after the country's intelligence agencies all agreed, in a public statement in October, that hackers with ties to the Kremlin breached US political organizations, and leaked key political figures' emails, Trump has continued to dismiss those claims.

In a tweet Monday, he said: "Unless you catch 'hackers' in the act, it is very hard to determine who was doing the hacking. Why wasn't this brought up before election?"

He's repeatedly downplayed the US attribution to Russia, offering up the idea in an interview with Time that it could also be another country such as China or "some guy in his home in New Jersey."

So if Trump is not listening to current intelligence officials, where is he getting his information?

Thus far Trump is surrounding himself with former military generals who may not have deep and technical knowledge of digital espionage and cybersecurity, but clearly understand aspects of signals intelligence, clandestine operations, and military hacking.

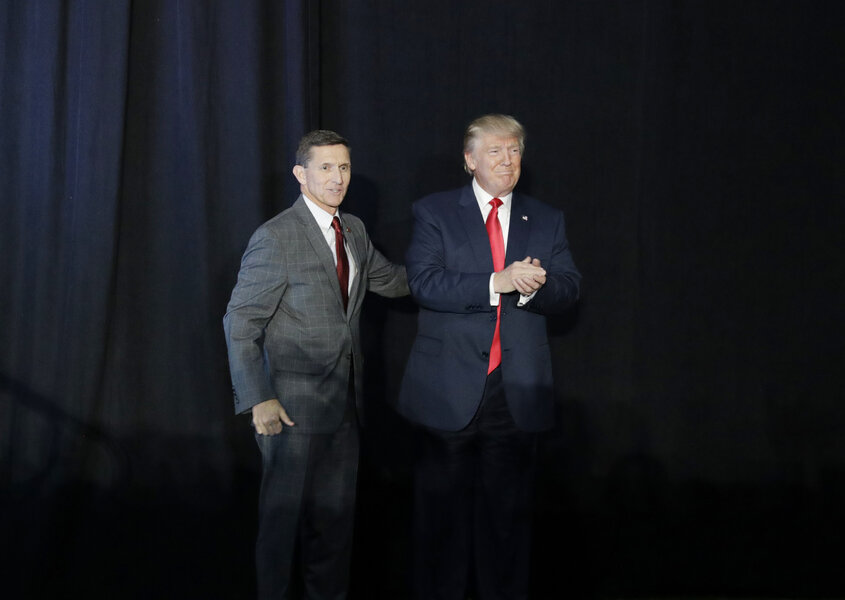

Michael Flynn may have the most sway over the president-elect on issues of cybersecurity. He's a member of Trump's transition team and the president-elect's incoming national security adviser.

Among the people around Trump, the retired Army lieutenant general and former Defense Intelligence Agency head may be the most knowledgeable when it comes to the current state of digital espionage and how a country such as Russia operates in cyberspace.

"It appears that Gen. Flynn, his advice to the president, specifically about cybersecurity will probably be taken very seriously," says Dale Meyerrose, a retired Air Force major general, who knows Flynn and served in the Bush administration as the first-ever intelligence community chief information officer.

Flynn's expertise and association with cybersecurity issues stretches back more than a decade, back to when he was in uniform, says Mr. Meyerrose. "I'm equally positive that Gen. Flynn couldn't fix a server to save his soul, but that’s not his job. His job entails an understanding, cause and effects and factors that go into decision making."

During the campaign, Flynn publicly differed with his boss on attributing the DNC hack to Russia. In an interview with Passcode, he said, "We should not be surprised that a communist state run by a totalitarian dictator wants to expose the weaknesses of capitalism and, frankly, show the level of corruption that exists in our political process."

Two years ago, Flynn bemoaned that the Defense Department was only in the "infant stage" of figuring out how to deal with computer weaknesses that were a byproduct of the increasing interconnectedness of government and industry information networks.

"We're not growing it fast enough," Flynn said of the Pentagon's cybersecurity capacity during a July 2014 discussion at the prestigious Aspen Institute, which hosts discussions among executives and government leaders.

At the time, he described US adversaries in cyberspace as "not just a nation-state like China or Russia or some of these other countries that are a bit more sophisticated" but also hacktivist groups such as Anonymous.

Neither retired Gen. James Mattis, appointed to head the Pentagon, nor retired Gen. John Kelly, picked to lead Homeland Security, appear to possess much expertise in digital issues.

Still, General Mattis is known as a deep and strategic thinker. In April, speaking at a Center for Strategic and International Studies event, he included computer hacking abilities in a list of five military capabilities that Iran has at the ready, such as a latent nuclear weapons program and ballistic missiles.

"There's the cyber threat, which if we’d talked three, four, five years ago, I’d have said it’s not a big threat," he said. "Today, I will just tell you I would liken it to children juggling light bulbs filled with nitroglycerine. One of these times they’re going to do something really serious and force a lot of foreign leaders to have to take it into account."

On June 2, current DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson swore in General Kelly – the country's longest-serving general – as a member of the department's advisory council and presented him with a Homeland Security Distinguished Service Medal.

During nearly half a century in uniform, including posts in Vietnam and more recently Iraq, he presented frank assessments that sometimes diverged from those of the administration. As head of the Southern Command, which spans countries in the Caribbean, South America, and Central America, Kelly oversaw the military detention center in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and disagreed with Obama's push to close the facility.

"They're detainees, not prisoners," Kelly told Military Times in January, at the end of his military career. "Every one," he added, "has real, no-kidding intelligence on them that brought them there. They were doing something negative, something bad, something violent, and they were taken from the battlefield. There are a lot of people that will dispute that, but I have dossiers on all of them."

For Kelly, Mattis, and Flynn, the Russian hacking issue promises to loom large over their roles, especially if government probes into the matter draw a direct line to Russian President Vladimir Putin, as NBC has reported.

Key Republican lawmakers such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and House Speaker Paul Ryan (R) of Wisconsin have supported additional congressional investigations into the Russian hacking allegations, setting the stage for a split among Republicans in Washington over a critical national security issue.

Of course it remains to be seen what the investigations will reveal, in addition to the findings of the probe ordered by President Obama into the election hacking, and whether or not Trump changes his views on the issue once he's in office.

The next administration may be in a position to craft clearer options for retribution when a country interferes with Americans' digital lives, be it the situation of Russia allegedly leaking private correspondences or China's history of stealing US trade secrets. It's unclear how or if Trump will consider appeals from Republicans and Democrats to publicly punish Russia for interfering in the US democratic process, as a way to prevent further meddling in domestic affairs.

"What's the strategy going to be with respect to acts that are destructive, that are maybe espionage, theft of intellectual property, or war? How do we develop our strategies as to how to deter and respond" to cyberincidents with a national impact, said Michael Chertoff, Homeland Security secretary under the Bush administration and now head of consultancy The Chertoff Group.

"There's an opportunity when the new group comes in to set a strategy on cybersecurity that deals with both the issue of whether there is a war-fighting element, but also the issue how do we deal with cyberactivities by adversaries that are maybe not on the scale of war but nevertheless serious thefts of intellectual property," Mr. Chertoff said.

If Generals Mattis and Kelly receive congressional approval to head their respective departments, "going after ISIS will probably have a cyber component," Meyerrose, the retired general, says of Trump's platform promise to dismantle the Islamic State.

Many privacy advocates and civil liberties groups have openly worried about growing levels of surveillance during Trump's administration, even suggesting that people begin using more secure forms of communication.

Earlier this year, amid the dispute between Apple and the FBI over access to the iPhone used by the shooter in the San Bernardino, Calif., terrorist attack, Trump lashed out at Apple for refusing to help the US government decode the encrypted phone.

Raj De, former National Security Agency general counsel and now head of Mayer Brown's global cybersecurity and data privacy practice, says he hopes Trump's nominees will be more transparent about digital surveillance operations.

"That's important in a democracy," said Mr. De. But, he said, "I don't think we've seen from the campaign that transparency has been a focus of his."