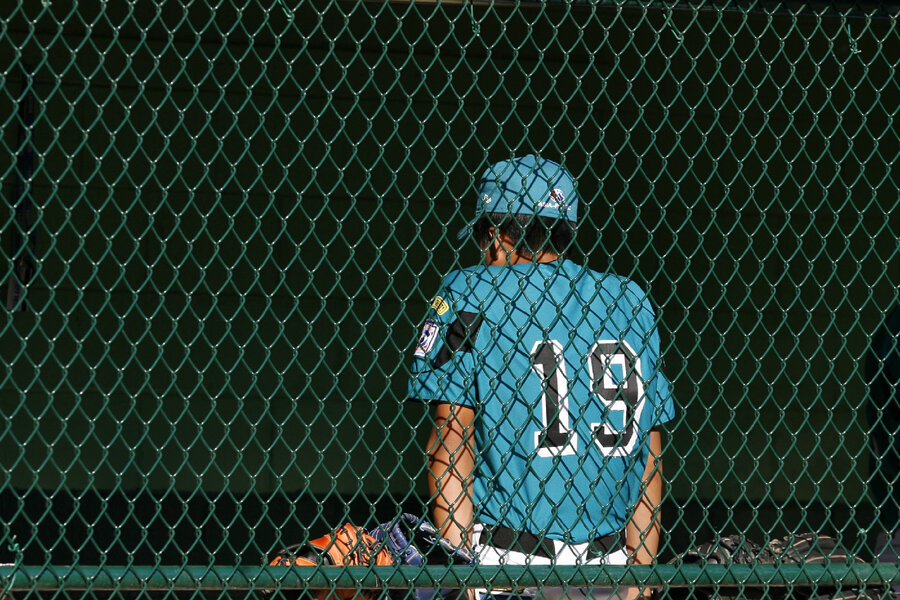

Opinion: When it comes to privacy, youth sports strike out

Loading...

It’s been nearly five years since a colleague of mine signed his 8-year-old daughter up for a regional competitive soccer youth league, but his concerns about her data privacy haven’t changed much.

At the time, my friend (who we'll call Jason for the sake of this article) noticed a lack of awareness and diligence on the basics of sensitive information. Team rosters included full names, full date of birth, and e-mail address of the parent – all in one place and available online for anyone who took the time to look.

In late 2012, California’s Attorney General, Kamala Harris, urged youth sports to develop more protective policies and there have been some changes. Today, Jason’s 10-year-old son’s soccer team roster looks very different. Details beyond his name and player number are available only with authentication, yet his daughter’s records from five years ago are still visible with a simple Google search.

While he acknowledges that youth sports leagues have a need for sensitive data, such as age, for authenticity; he questions the lack of urgency around data that was shared too broadly and has been retained for much longer than necessary. Despite raising these concerns in e-mail discussions with league officials, his daughter’s personal information remains accessible and vulnerable online.

After speaking with Jason, I took a closer look at privacy in youth sports. And it turns out, I think you should, too. Reading privacy notices may not be your first thought when you sign your child up for a youth sports league, but because you’ll provide some form of your child’s birth certificate and other personal information, it’s a key opportunity to be a privacy-savvy parent.

As Jason noted, youth sports organizations have valid reasons for collecting sensitive and personal information. Age, weight, and photo verification are key elements of a legitimate and important safety protocol for all ages. This information is typically kept on player cards, held by a designated volunteer, and verified weekly before games. Other registration information, including date of birth or birth certificate, school attendance history, home address, health insurance and medical clearances is stored electronically, often on third party vendor sites. Collection, storage, access, and sharing all create points of risk that need to be evaluated by the organization.

One privacy risk is that any weakness in data handling practices for sensitive or personal information creates the potential for medical and financial identity theft, something that is on the rise for children because it often goes undiscovered for many years. Children’s identifications are especially vulnerable because they don’t have an existing credit file, so their identifiers aren’t under the watchful eyes of credit monitoring agencies. Sometimes, risk can be reduced by something as simple as saving and sharing age or birth year rather than full birthdate.

Another privacy and safety risk is the exposure of the team’s details online that includes specific details about each child and the child’s location. Coaches, team parents, and players all have a need to know when and where the games are played, but posting that information publicly, especially as the default setting, can create space for anyone to learn the whereabouts of a child. Something as simple as not including names and jersey numbers can reduce risk.

If you search your child’s name online and they’ve played competitive youth sports, chances are they’ll have a digital footprint. Player histories, dating back several years, are often available online. The risk is that once your child’s information is public, it is searchable and available forever.

To help reduce this risk, ask site administrators to delete your child’s data once it’s no longer needed and do a periodic search to verify that the information is no longer visible.

Concerns about protecting the online data of children and youth are on the rise, likely because usage of data has risen both in schools and at home. More parents are realizing that if an app is free, its funding may come from the use and sharing of personal information. Added to an increasing awareness of what “free” means, are the growing number of news reports about data breaches or hacks and internet surveillance. Some parents and advocates are especially concerned about data used to market to kids. Others are worried about ID theft or safety.

Rising concerns have led to numerous legislative proposals in Congress and state legislatures. More than 180 state bills regarding student data protection were introduced this year – 46 states considered and/or passed student data privacy laws in 2015 – and several federal proposals are being discussed in Washington. There are seven to eight different bills or amendments on Capitol Hill, including the Messer-Polis bill.

But youth sports leagues aren’t necessarily subject to the same regulations as K12 schools, so it’s especially important for parents and leagues to balance privacy and safety risks with strong data practices.

Here are some tips for parents:

- Birth certificates: If you must provide a copy, ask where it will be stored, what safeguards are in place, and how and when it will be disposed of. For paper copies, the disposal answer should be cross-shredding or return of all originals or copies. When providing a copy, it is not safe to send any sensitive documents by e-mail.

- Photos and public info: Ask if your league has a social media policy or photo guidelines. This can tell you how much personal information will be shared publicly when photos are posted and whether parents can request limits (ex: last name and first initial or position and team).

- Rosters: Note what type of information is shared on the team site and league roster. The combination of information like full names and birthdates is often not necessary and can contribute to identity theft. Year of birth or age should be sufficient in most cases.

- Vendors: Be aware of who is handling your child’s information and read vendor privacy notices. Sports team websites, league online registration, club communications, and team schedules should all have access control limits in-place by default. Be sure to choose a strong password to protect your registration information.

Leagues should consider some of the best practices from the US Department of Education’s Privacy Technical Assistance Center and the Federal Trade Commission’s guidance about the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (which concerns collection and use of personal information for children under age 13.)

Most privacy advocates and policymakers agree on several key points that can be helpful for coaches and leaders of youth sports leagues, including:

- Always get parent permission, and make sure parents know what information you’re collecting about kids and teens, and why it’s needed (for example, certifying age for an appropriate league, or maintaining emergency contact information for all players.)

- Don’t over-collect. Leagues should only ask for player and family information that is necessary for league purposes.

- Minimize the data you keep. For example, even if a coach needs to see an exact birthdate to certify a player, the information stored online might only need to be month and year of birth. (Hackers love exact birthdates, because they’re especially useful for ID theft like creating fake credit card accounts.)

- Don’t keep personal information longer than necessary. Data kept over multiple years increases the risk of personal information being hacked.

- Review your league – and team – practices for protecting and securing player information. Personally identifiable information shouldn’t be stored online where anyone can access it.

- Communicate clearly and concisely to parents about what privacy means to your organization and steps you take to protect personal information. Build trust by doing what you say you will do.

Stacy Martin is the senior privacy manager for Mozilla. Follow her on Twitter @StacyMoz. Alan Isham, Alan Simpson, and Tiffany Schoenike, all members of an informal Privacy Awareness Coalition, contributed to this article.