Olympics: How top athletes live the spirit after retiring from sports

Loading...

When Kerri Strug landed her vault on an injured ankle at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, helping US women gymnasts win their first gold medal ever as a team, she became a national hero at age 16. And yet, even before entering college, she faced a transition that for many athletes is akin to a midlife crisis and retirement wrapped into one.

"I think for many Olympians it's difficult. [The Olympics] have been a goal for the majority of their life, and you don't want to look beyond that because you don't want to lose focus," says Ms. Strug, who now works for the US Department of Justice. "But if you're willing to [put] so much time and energy and passion in one area, there's no reason you can't do it elsewhere."

While many athletes struggle to transition to "civilian life," as one put it, those who are successful bring with them a wealth of tools that enable them to contribute to their communities in a unique way. For them, the Olympic experience serves as a crucible for forging qualities of character that enable them to bring out the best in others.

"It was awesome to ... be able to see Olympians in each and every one of [my students]," recalls Olympic decathlete Dave Johnson, who went on to work in special education.

At one point, he manned a "resource room" for students who had gotten kicked out of class. Many were living with grandparents after their parents had divorced or died.

Mr. Johnson, anchored by his Christian faith, as he had been when he won a bronze medal in 1992 despite breaking a bone in his foot, tried to be a steady presence for the young people. "A couple of them were thinking, 'I'm going in a bad direction, but academics can help me get out,' " he says.

Branching out

Johnson is not unique in finding fulfillment by branching out beyond the narrow goals of a focused athlete to work with others. "In a way, you can afford to be very selfish in the Olympics," says Matt Biondi, one of America's most decorated swimmers. "Families don't work that way, communities don't work that way, jobs don't work that way."

After years of motivational speaking, Mr. Biondi says he got tired of parachuting in and out of kids' lives. So he decided to become a high school teacher in Hawaii.

One of the big challenges for him and others has been measuring progress outside sports. Life beyond the pool isn't about a millisecond shaved or a stroke perfected.

"There's a certain simplicity in sports," says Biondi, who now finds himself fielding parent complaints rather than requests for autographs. "[Outside sports], there's not that singular sense of purpose. It becomes a new challenge to be able to be true to yourself and to keep after your goals ... and yet be tolerant."

For many, replacing the thrill and satisfaction of competing is difficult to do. Bill Koch, the only US cross-country skier ever to win a medal, could have easily rested on his laurels after retiring from racing in 1984. But he continued to pursue his Olympic dream, trying out for the team up until 1998 – almost a quarter century after he won his medal.

In between, he designed ski trails, launched an outdoor clothing line, and later led unorthodox ski trips on Hawaiian beaches. Was any of it ever as rewarding as ski racing? "No," he says unhesitatingly. But for Mr. Koch, now retired in Vermont, racing was never the end goal. "Whether racer, surgeon, author, cook, garbageman ... whatever we do, it's not what defines us," he says. "It's what's inside that defines us."

An identity independent of sports?

But finding an identity independent of sports can be hard in an era when the Olympics represent not just patriotism, but big paychecks. "When I was 10 and dreaming of the Olympics, it was for the uniform and USA on my back," says Picabo Street, a two-time medalist in alpine skiing. "Now it's the uniform that comes with all the patches on it that represent all the sponsorship dollars."

If the endorsements bring new pressures and demands, though, they also bring greater opportunities. Successful athletes in the Olympics can make a lot of money and set themselves up for life.

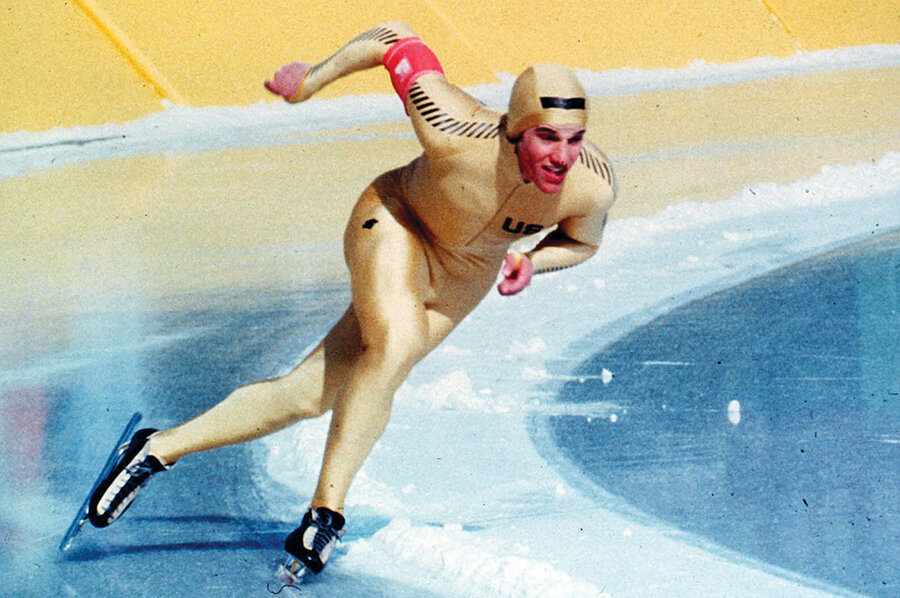

"I think as important as [the Olympics] were in the past ... they may have even become more important," says former speed skater Eric Heiden, now an orthopedic surgeon in Utah. "What you do there, that can change your life." Nevertheless, Mr. Heiden remains nostalgic for the days when he and his teammates were fueled by the sheer enjoyment and camaraderie of their sport.

Money doesn't have to be a corrosive force, of course. As more of it trickles down to the athletes today, it can help them lay the foundation for a life after the pool and oval track.

"What we have now in our Olympic sports is we have kids growing up who know they can make a career of it," says Biondi. "That has elevated our sport tremendously."