What role for Kurds in the ‘new’ Syria? They’re getting mixed messages.

Loading...

| London

On paper, the agreement to integrate a powerful, U.S.-backed Kurdish force into the national army and institutions of the “new” Syria promises unity, peace, and mutual respect for the country’s long-disenfranchised Kurdish minority.

The deal on “principles” brings a much-needed boost to Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, following the bloody crackdown on armed Assad-regime remnants that had mounted multiple attacks on forces of the new government.

In a matter of days, that violence left an estimated 800 to 1,500 Syrians dead and buried in mass graves – mostly from the Alawite minority and including many civilians – and tarnished Mr. al-Sharaa’s pledge to prevent sectarian revenge.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onBringing the U.S.-allied Kurdish militia under the umbrella of Syria’s army sends an important message about national cohesion amid heightened concerns over minority rights, which were not assuaged by the “new” Syria’s interim constitution.

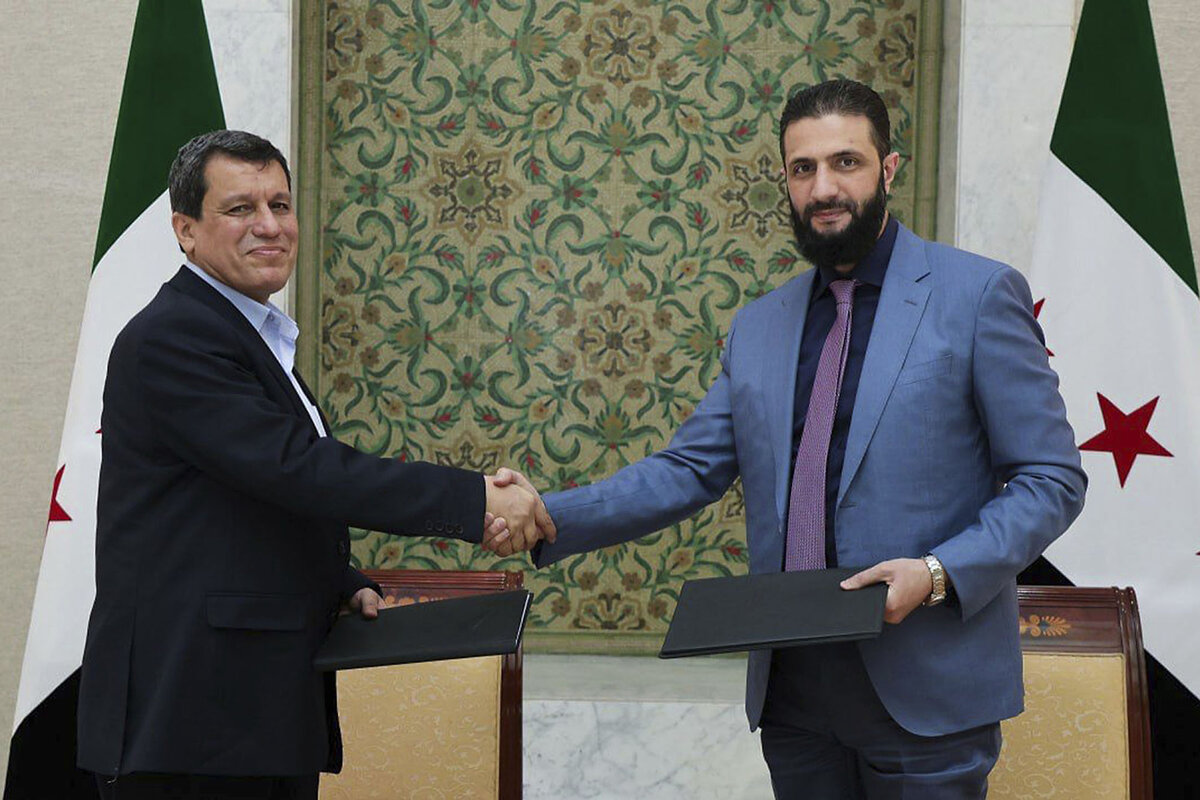

The Syria-Kurds deal, signed March 10, comes as Gen. Mazloum Abdi, commander of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), assesses President Donald Trump’s presumed desire to limit support and shrink the U.S. military footprint of some 2,000 troops in Syria.

The SDF controls northeast Syria, its rich oil and gas fields, and detention camps that, according to the United States, hold more than 9,000 Islamic State fighters and their families.

Under the deal with Mr. al-Sharaa’s government, the SDF agreed to integrate “all civil and military institutions” with the new Syrian state by the end of the year, under “one flag.” Syrians celebrated the deal as a key step toward unification, with flag-waving and gunfire in Damascus and in Kurdish-controlled regions of the northeast.

Yet Syria’s interim constitution, approved Thursday by Mr. al-Sharaa, only vaguely enshrines the rights of minorities. It maintains Arabic as the only official language, as well as the “Arab” identifier in the Syrian Arab Republic. Notably, the SDF agreement references the “Syrian state,” while Mr. al-Sharaa signed as head of the “Syrian Arab Republic.”

The constitution has disappointed Kurds, the country’s largest non-Arab minority, who make up 10% of the population but were not specifically mentioned. The political wing of the SDF, the Syrian Democratic Council, declared its “complete rejection” of the draft constitution, warning in a statement that it “reproduces authoritarianism in a new form” and restricts political activity. Kurdish news outlets broadcast footage of street marches against the text.

And while Mr. al-Sharaa has called for disbanding all of Syria’s mosaic of armed militias – including his own Islamist Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which in early December led the toppling of the Assad dynasty – critical questions remain about how the SDF integration will be achieved.

“It’s very symbolic, it’s historic, but at the same time we have to put this into context,” says veteran Syrian journalist Ibrahim Hamidi, editor-in-chief of the London-based online magazine Al Majalla.

“Both [sides] needed the agreement and wanted to buy time. ... It’s a win-win,” says Mr. Hamidi, of the nine-month timeline to resolve differences. “But does it mean they addressed the divide between Arabs and Kurds? No.”

Shifting power balance

Before the fall of President Bashar al-Assad, he notes, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham had a force of 17,000, while the SDF had marshaled 70,000 fighters trained and equipped by the United States to battle the Islamic State, which lost its hold on territory in 2019.

But the SDF’s numerical advantage has been changing since December, with recruitment growing the forces under Mr. al-Sharaa’s command to 50,000 men, and an allied reserve of another 50,000, says Mr. Hamidi.

Not yet clear is how the Trump administration plans to handle the SDF, which received $186 million in U.S. funding last year. The Department of Defense request for $148 million for 2025 noted that American support was “critical” for detaining Islamic State fighters and to “prevent the group’s resurgence.” But media reports suggest that the Pentagon has drawn up withdrawal plans with 30-, 60-, and 90-day options.

“The [Syrian] government has this master plan to form a new army, a new structure, and you have to fit in. ... They want to dilute the militias,” says Mr. Hamidi, who interviewed key officials on a recent trip to Syria and has interviewed General Abdi. The government expects SDF fighters, for example, to join the army not as a group but as individuals, and to not serve in their native region.

Such conditions are anathema to the SDF especially, which views itself as a necessary bulwark of protection for Syria’s Kurds.

The new interim constitution affirms that “The state guarantees the cultural diversity of Syrian society in all its components, and cultural and linguistic rights for all Syrians.” It also bans paramilitary formations separate from the army.

The Turkey factor

Another challenge is that while Mr. al-Sharaa’s regime-toppling offensive enjoyed strong Turkish support, Turkey considers the SDF to be a Syrian offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Turkey deems a terrorist group.

In late February, from his prison cell in Turkey, PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan called on his fighters to “lay down their weapons” after a four-decade struggle and to “dissolve” the PKK.

Mohammed Dirki, a Kurdish civil engineer living in Damascus, notes the American hand in the Syria-SDF deal.

“The Syrian government is to be the guarantor between Turkey and the SDF. It will help solve problems between them,” he says.

“When you are in a position of strength, you can speak,” says Mr. Dirki. “Kurds gained a voice thanks to their alliances with America. ... For sure there was American pressure for this agreement to take place. Without it, this agreement would have been impossible.”

Another ethnic Kurd in Damascus, Salah Surakji, has his own perspective. He spent six years in detention, and lost his brother and six other members of his family, who he says are among 1,500 Kurdish “martyrs” from Damascus killed in Syria’s civil war.

Such sacrifices were made not just for the Kurdish cause, he says, but for the freedom of the entire nation.

Mr. Surakji figures the SDF represents just 15% of Syria’s Kurds.

“We agree with the SDF on the rights of the Kurds; however, we do not agree with the SDF on its principles [of federalism],” he says. “Our country must remain united.”

Relinquishing weapons

That is the stated aim of the SDF agreement with Damascus, which, as vague as it is, “is definitely a milestone for Syrian Kurds,” says Mohammed A. Salih, a senior fellow at the Philadelphia-based Foreign Policy Research Institute and an expert on regional Kurdish affairs.

Nevertheless, he cautions, integrating the SDF into a national army will be “extremely challenging,” not least because of recent violence.

“One thing that minority groups in Syria learned is that they cannot put down their weapons, because even if Ahmed al-Sharaa says all the right things, there are so many rogue elements in his newly formed military – from the jihadis to the Turkish-backed forces – which played a major role in killing of Alawites,” he says.

Both those groups have a “strong animosity” toward the Kurds and SDF, Mr. Salih says, so it would “be very unrealistic” for Kurds to trust Mr. al-Sharaa’s word alone and give up their military capabilities.

“If the SDF is even partially dismantled, that could be a doomsday scenario for Kurds under the current circumstances, given the violence in the coastal areas and Mr. Sharaa’s own contradictory moves regarding Kurdish rights,” he says.

Dominique Soguel and Walaa Buaidani in Damascus, Syria, supported reporting for this story.