Coffee without end: Oasis village tests limits of hospitality

Loading...

| JUBBAH and HAIL, Saudi Arabia

Alighting from an Uber at the souq in downtown Hail, the reporter gets a warning from his young driver about his next destination.

“Don’t eat or drink before you go to Jubbah,” he says.

It’s an odd and ominous warning to receive in Hail, a northern Saudi region so famous for hospitality that it has inspired centuries-old Arabic poems and modern Youtube videos – and where you are never more than a few minutes away from your next lunch invitation.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onHow generous is too generous? In the Saudi oasis village of Jubbah, where doors are never closed, hospitality that once served as a lifeline for desert travelers pushes politeness, and guests’ capacities, to the limits.

But in the palm-lined oasis village of Jubbah, 72 miles north of Hail in the desert, where generosity toward guests was ingrained in generations who endured severe hardship, residents provide hospitality as extreme as the elements – even too extreme for Hail locals.

“You will enjoy it,” advises the driver, who today lives in Hail but has family back in Jubbah, “but they will host you until it hurts.”

Jubbah is a village whose residents never close their doors – really – an invitation for anyone to walk in unannounced for coffee, dates, tea, a meal, or to spend the night.

“Our prophet taught us: Be generous to your guests,” says village resident Ayed bin Mohammed al-Ayadeh, who, like his great-grandfather before him, greets guests at his ancestral home and farm with dates and cookies. “Which is why our entire community and daily routines revolve around hosting.”

As Jubbah residents pursue generosity with a religious zeal, they compete for guests: Who gets to host them and serve them lunch? Those left off a visitor’s itinerary can become upset.

Village of open doors

On a Saturday in February, the doors to Jubbah homes both small and large are open.

“Welcome!” one resident calls as visitors walk past his open gate, waving them to enter. “Hello!” beckons his neighbor from the garden.

Jubbah residents typically reserve about 70% of their home for guests – including an ornate majlis guest hall with plush chairs and a fireplace, courtyard, sleeping quarters, a bathroom with perfume, even parking – leaving a few small, spartan rooms in the back for themselves.

Most of the courtyards open onto the main road to make it easier to flag down an out-of-towner.

“Here you are judged by your hospitality,” tour guide Rami Shimri says, pouring coffee in his father’s plush majlis. “You have to have a majlis and you have to be on call for any visitor. It is our way.”

Entering Jubbah from the south, Mr. Shimri’s family home is the first of dozens whose owners will invite you in.

It is by design; his father selected this location at the outskirts so that their majlis would be the first to greet visitors with coffee and incense.

And so, the invitations begin, from home to home. It’s an endurance test of politeness – and the stomach.

Within an hour of being pulled into different guest halls a culinary cycle emerges: coffee, dates, tea; coffee, dates, tea, and biscuits; coffee, dates, fruit, and tea.

Hosts do not take “no” for an answer. Even covering your cup with your hand fails to stop the coffee flowing.

“Please show us mercy, we have already drunk 20 cups of coffee today!” says one Saudi visitor. “I can’t have another date,” says another, clutching his stomach.

“Just put the coffee pot down,” a Saudi guest says to a teenage host eager to pour a third cup. It’s a break from Arab etiquette in which the guest always defers to the host. “Just. Put. The. Coffeepot. Down.”

“This is only the introductory coffee,” the host says, stone-faced. “I invite you for an informal coffee at my residence out back. Now, please eat.”

Hardship hospitality

It may seem forceful, but residents say it is a hospitality shaped by hardship.

When the ancestors of today’s residents settled this oasis 500 years ago, upon a dried lake and ancient hunting grounds in the heart of the Nafud desert, they relied on and improved existing artesian wells that were already many centuries old, Jubbah historians say.

They dug and fortified 130-foot-deep wells in the sand, often deadly work, to collect groundwater and rainwater. Teams of two camels would pull up the pails of water in a mill system.

For the ensuing centuries, before modern agriculture took root in the mid-20th century, villagers struggled to grow crops beyond date palms. Separated from the nearest town by dozens of miles of desert, they relied mainly on dates, ghee, and wheat kernels to feed their families.

“It was from this hardship, fear, and near-starvation, that the community of Jubbah formed a sense of solidarity and a life-or-death concept of hospitality,” says Nasser al-Shaweini, a local historian and curator of the Nasser Shaweini Museum. “It was a self-reliance that prized what little that they had, and shared with others.”

Mr. Shaweini guides museum visitors to an oriental carpet and a large platter of bananas, apples, kiwis, and oranges.

“We lacked resources, but had hospitality in abundance.”

This hospitality was a lifeline for travelers.

Jubbah was a vital stop for caravans coming from the Levant down into Hail and further into the Najd region of central Arabia. The route took them through the harsh, 40,000-square-mile Nafud desert that stretches from today’s Jordan down into Hail.

Travelers would arrive in Jubbah, two-thirds of the way across the Nafud, parched after six arduous days.

The visitors and their camels would be greeted with water that residents would immediately pump into pools and troughs at the front of their homes, through canals that still exist today.

The guests were fed dates, wheat, and ghee – for days or weeks – and upon their departure were given a large batch of dates to sustain them on the next leg of their desert journey.

“The best dates, ghee, wheat, whatever we had were set aside for visitors and guests,” says Mr. Ayadeh, dipping a date into a ghee-date molasses syrup and handing it to a visitor, “because we didn’t know when the next time our guests would eat, find water, or rest after they left.”

Tourism without hotels

Jubbah, which now boasts trained tour guides, is looking to share its unparalleled hospitality – and wealth of sites – with world visitors.

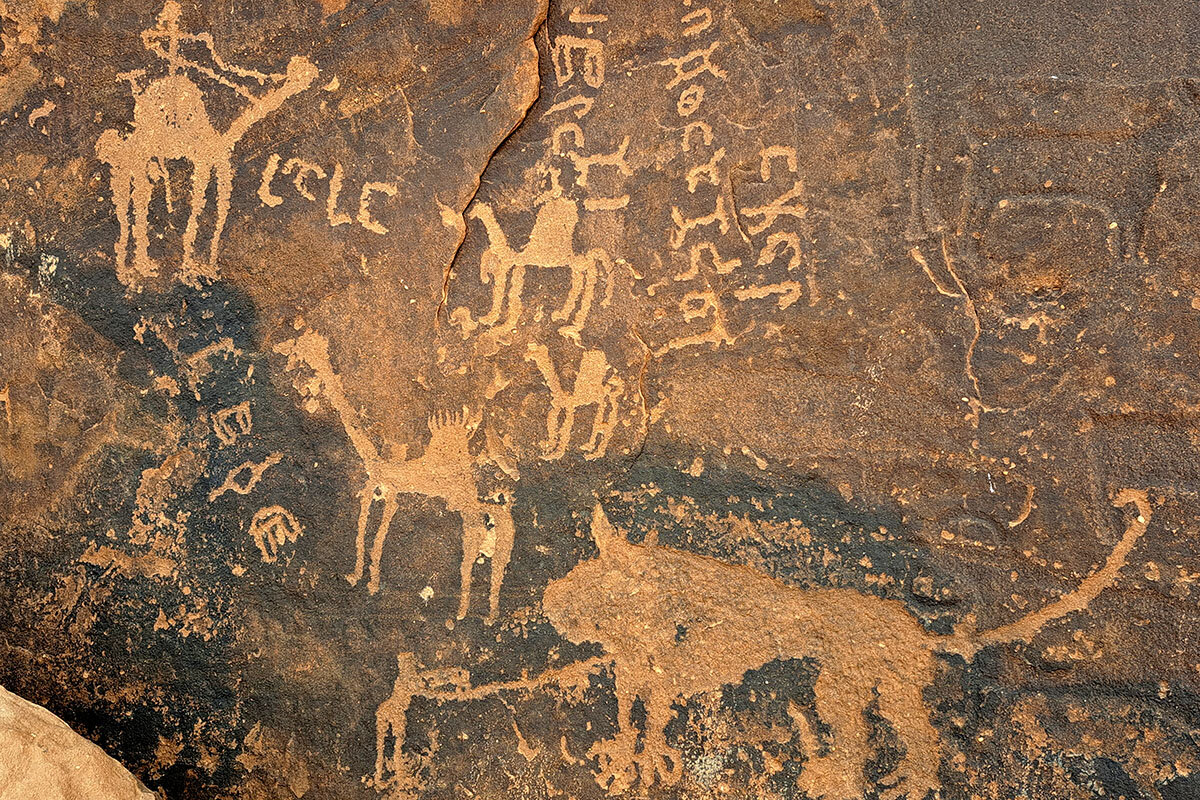

The village is eager to showcase its breathtaking ancient rock art and petroglyphs, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2015. There are also nearby desert camping sites, and idyllic date farms and mud-brick homes across the village.

Several residents have expanded their ancestral guest halls into cultural museums at their own expense to showcase the area’s history – in between dates and coffee for their guests.

Despite the push for tourism, hotels are forbidden, as far as Jubbah residents are concerned.

They are eager to offer their traditional rooms to visitors to spend the day or night – preferably several – for free.

“We always have a room for visitors to rest and stay. This is the least we can do and it would be shameful to monetize it,” Mr. Shaweini says as he shows off his cushioned guestroom.

Leaving is a challenge. Only a series of excuses and a race through the town avert multiple dinner invitations. Several people in the street wave at the departing vehicle, urging the visitors to pull over and stay “for just a little while longer.”

Two days later, at the Hail Airport, a stranger quizzes the reporter on where he had visited.

“I am from Jubbah,” the stranger exclaims. “Why didn’t you tell us you were coming? We would have readied the coffee pot for you!”