Hajj without the crowds: How pilgrims are persevering

Loading...

| AMMAN, Jordan

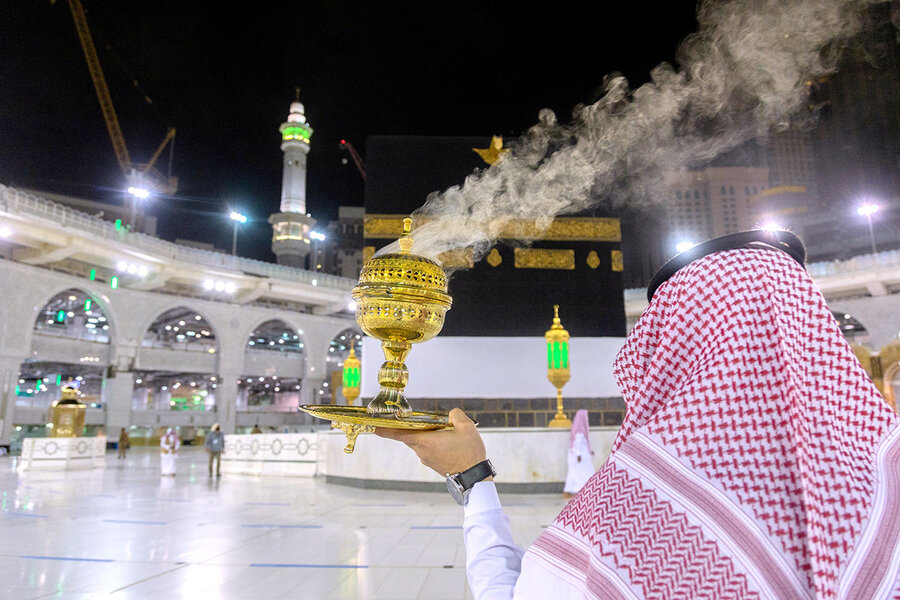

Quarantines, social distancing, praying in masks. The Islamic world has never seen a hajj like this in more than 1,400 years.

While the hajj’s hallmark of community has been stripped away by coronavirus precautions, other tenets have been intensified for pilgrims who have spent months living in uncertainty: determination and hope.

This year’s hajj, a rite all adult Muslims should complete in their lifetime, is scaled down and micromanaged in what Saudi authorities are calling an “exceptional pilgrimage” for exceptional times.

Why We Wrote This

The coronavirus has hit prayer gatherings and religious rituals especially hard. And the annual hajj is perhaps the quintessential mass participation religious rite. Yet, even without crowds, the pilgrimage still has meaning.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

While 2.5 million people normally participate over the same week, this year a few thousand Muslims residing in Saudi Arabia – a mixture of Saudis and foreign nationals – were chosen for the pilgrimage that ends Aug. 2. A majority of them are frontline workers and health care professionals who have been leading the fight against COVID-19.

“Reducing the number of pilgrims for Hajj 2020 was a necessary precaution to make sure the virus does not spread while there still isn’t a vaccine,” the Saudi minister of Hajj and Umrah, Dr. Muhammed Saleh bin Taher Benten, said in a statement.

Conducting the hajj this year is a feat few thought possible. Mecca has been mostly closed the past four months, and Saudi Arabia’s COVID-19 cases have passed 275,000, with several thousand new cases per day.

Lines around the Kaaba

Precautions are many. Luggage in brand new bags containing clothing and supplies – all provided by the government – is disinfected, sterilized before it is moved from one stage to the other. Pilgrims’ temperatures are taken before they enter a bus, a site, the Kaaba, or return to their hotel rooms.

Multicolored lines around the Kaaba are painted to ensure pilgrims are two meters apart as they walk in staggered lines for the counter-clockwise tawaf circles around the black shrine.

Pilgrims are given set times for their visits, ensuring that only a couple hundred are at a site at a single time; face masks are mandatory.

In addition to prayer books and Qurans, hand sanitizer is an essential item tucked into their fanny packs.

But perhaps the greatest change is the lack of the community and camaraderie that marks the annual rite. Normally contingents from each country camp, sleep, cook, and perform the stages of hajj together, building bonds and meeting Muslims from across countries and cultures.

This year, after spending a week in home quarantine and undergoing multiple COVID-19 tests, pilgrims spent four days of self-isolation in their hotel in Mecca before embarking on hajj rituals.

It continued a way of life many had already become accustomed to.

Saudi national Hamza al-Harzi, a field emergency medical specialist for the Saudi Red Crescent Authority, had spent the past five months self-isolating while testing and providing urgent care for COVID-19 patients in their homes in Riyadh.

Unable to see his father and mother for most of the year, he has connected with his family via video calls.

“My parents were elated to learn that I was going to hajj; it was the best news they have had all year,” Mr. Harzi says in a Zoom interview facilitated by the Saudi media commission. “They are with me as I pray. In a way, this pilgrimage connects us.”

Virtual camaraderie

To avoid mixing of large numbers of pilgrims, their meals are placed at their hotel-room doors; even their prayer times are scheduled.

Instead, the camaraderie has gone virtual.

WhatsApp groups, FaceTime, and Zoom meetings have replaced the meetings in the cafeteria, the prayer groups, or huddling together in mosques long after prayer time.

Fawzia Yusof, a Malaysian nurse who works at a Riyadh hospital, has spent much of her days studying and practicing prayer supplications and hajj rites on Zoom with several other Malaysian and Singaporean pilgrims. They, like her, are sitting in nearby hotel rooms.

“Even though I have never met them in reality, we are becoming close,” Ms. Yusof says via Zoom interview.

“Most of our time we are spending together virtually, learning the rituals of hajj, and chitchatting about life and the food.”

Ms. Yusof, who last saw her husband and two daughters on March 10 during a visit home to Malaysia, speaks with her children on FaceTime when not participating in hajj activities. She has prepared her prayers for Mt. Arafat, the site outside Mecca where Muslims believe the prophet Muhammad gave his farewell sermon.

“My prayer will be for COVID to disappear so I can reunite with my family and the world can heal,” she says, visibly emotional.

“I want to pray that coronavirus is gone,” she shakes her head. “Gone, gone, gone.”

Story for the grandchildren

Family is also on the mind of Kehinde Qasim Yusuf, an assistant professor at a university in Medina from Australia.

Mr. Yusuf normally takes the summer off to spend time with his three children in Australia. Unable to travel this year due to the coronavirus, he has not seen his children since August 2019.

“After not being able to travel and being alone, having the chance to cap off the year with hajj makes it amazing,” he says.

“To be in these tough circumstances and to still be able to commit to the act of worship and tawaf in Mecca to pray for people across the world who are sick, dying, and have lost family is something really special. This is a story for my children and grandchildren.”

Atta Farida is another pilgrim who has found a positive outlook through hajj after her life was dramatically altered by the coronavirus.

Mrs. Farida’s husband lost his job with an oil and gas company in eastern Saudi Arabia in June, part of the larger economic shock from the pandemic.

Her husband has been looking for work to continue living in Saudi Arabia as they prepare for a return to their home country of Indonesia. When they found out earlier this month that Mrs. Farida was chosen to embark on the hajj, she thought it was a mistake.

“Every day I cry, this is such an unexpected blessing,” Mrs. Farida said.

Her prayers at each station this hajj are that her husband can find a new job soon and that their daughters would be able to continue their education.

But no matter the outcome, she says she has found a new outlook through pilgrimage.

“I learned that Allah will not let you down,” Mrs. Farida says. “God will give you something beautiful when you are down. You never know from where it will come.”

“Point of unity”

In brief interactions, Mr. Yusuf has met pilgrims from Albania, Afghanistan, India, Ghana, and Ethiopia. Just the knowledge that other nationalities are taking part in the pilgrimage at the same time serves as a source of “strength.”

“Mecca is the one place that unites Muslims across nationalities, ages, languages; all the dividing lines of rich and poor, Black and white, disappear,” says Mr. Harzi, the Saudi health care worker.

“Hajj is not just a requirement for Muslims, it is a point of unity. This is why it is important for it to continue.”

But as they continue the steps of the hajj through Sunday, pilgrims say their smartphones will be turned off and the social media that has acted as their lifeline this year will be put aside. After months of isolation, they will no longer be alone.

“When I am at Mt. Arafat, there will be no FaceTime,” Ms. Yusof says with a smile. “It will only be me-and-Allah time.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.