Iraq's Kurds scramble to fend off new Islamic State assault

Loading...

| Mala Qara, Iraq

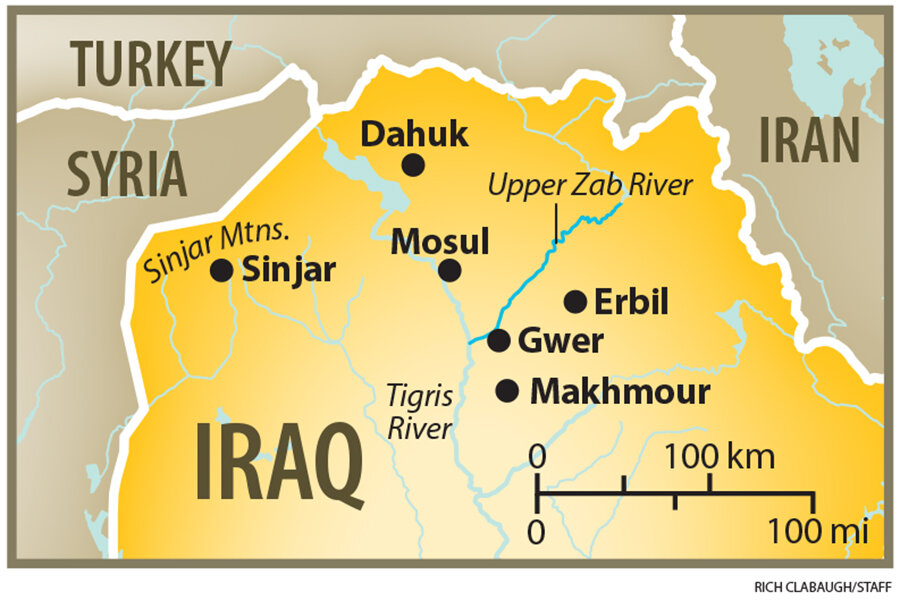

In the bright January sunshine, Kurdish fighters pose for photographs and dance around an armored vehicle seized from Islamic State militants in Gwer, a small but strategic town in northern Iraq.

The mood was far more somber earlier this month after a surprise IS attack left dozens dead, highlighting the vulnerability of Kurdish peshmerga forces and their regional capital, Erbil, where American military and civilian personnel are based.

Backed by US air power, Kurds have been largely on the offensive against IS since last summer. Kurdish forces have clawed back territory and painstakingly restored their warrior image. But throughout January, IS forces have carried out stinging attacks along the frontline of northern Iraq, demonstrating their capacity to modify tactics and threaten Kurdish gains.

“There were some gaps in our security, but we’ve taken care of all these gaps and this will never happen again,” vows Qadir Qadir, a peshmerga commander in Gwer, where the frontline is demarcated by the Upper Zab river.

Kurdish commanders reckon they can see off the renewed IS assaults, but admit this depends on ongoing US-led coalition airstrikes. And they stress they are badly in need of improved weaponry in the fight against IS, which controls large swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria.

In his State of the Union address on Tuesday, President Barack Obama said the military campaign against IS was working. “This effort will take time,” Obama told Congress. “It will require focus. But we will succeed."

Range of new IS tactics

The surprise IS attack began after dusk on the night of Jan. 9, with 160 militants crossing the foggy river on 15 boats provided by Sunni Arab villagers. In total, IS forces launched nine attacks in the sector of Gwer and Makhmour, two towns on the outskirts of Erbil, where forces are under the command of Sirwan Barzani.

Mr. Barzani says the attack was foiled with the help of coalition airstrikes, the arrival of a quick reaction force of 615 men, and the guidance of nine US military advisers present in the area at the time.

Many of the Kurdish combatants say the assault exploited a technology gap between the two sides. “In all of my sector, which covers 230 kilometers, we don’t have any thermal or night vision goggles,” explains Mr. Barzani, nephew of Kurdish President Massoud Barzani. “They [IS fighters] are always using new technologies, so we have to be weary about that because they are not an easy enemy at all. They are really dangerous.”

New IS tactics include the use of armored vehicles and Humvees to stage suicide attacks – a lavish sacrifice in the eyes of outgunned peshmergas and a potent reminder that the IS stockpile includes weapons seized from the Iraqi and Syrian armies.

In Barzani’s sector, peshmerga forces are digging channels three yards wide to stymie such assaults. There were nine assaults just this month, including two halted by air strikes and three that hit close to their targets.

By all accounts, IS fighters in Iraq and Syria are trying to lower their profile: traveling in civilian vehicles rather than convoys; shifting their training centers underground; and concealing their weapons in schools or mosques. Most attacks now happen at night and aim for an element of surprise. They are said to be using small drones to scout out Kurdish positions and aluminium foil blankets to help conceal their movements from thermal vision devices.

More coalition help needed for long haul

Kurdish commanders credit the coalition airstrikes with facilitating their military advance, including the rapid capture of the Sinjar mountain range in December. But they insist that far more weapons and ammunitions are needed in order for the peshmerga – whose experience is limited to guerrilla warfare – to protect their turf. Barzani’s sector so far has received only two German anti-tank missiles and some ammunition.

“You can’t send one shipment and say we are done. This (war) may last for three years,” Jabar Yawar Manda, secretary-general of the Ministry of Peshmerga, the Kurdish defense ministry, told the Monitor. “In the last six months we have lost about 800 peshmerga. More than 4,000 men were wounded on duty. This is a big number for us.”

For the Kurds, the frontline now spans more than 600 miles, stretching from the Sinjar mountain range on the border with Syria toward the town of Khanaqin near Iran. The front is divided into eight zones, five of them still considered “trouble spots,” areas in which airstrikes and fighting continue. Field commanders report back to Erbil, where the top brass and their foreign advisers decide where to employ airpower.

“The peshmerga are prepared to die defending their land, but the airstrikes play a big role,” says Polla Mohammed, a member of the military operations room in the oil-rich district of Kirkuk. “If there were no airstrikes, they could fight us for 10 hours instead of four or five. The weather is their only ally. Whenever there is fog, they launch surprise attacks.”

IS attacks rebuffed near Kirkuk

Like in Gwer, the Sunni militant group recently took advantage of low visibility to stage attacks around Kirkuk, but were rebuffed.

“ISIS is going down, they are on their back foot. They are staging small attacks with suicide bombers to create chaos, but they don’t have the manpower they had before. They’ve lost many of their supporters in Iraq because of their brutality,” says Mr. Mohammed.

The next test on the horizon for Kurdish forces is Sinjar City. Victory there would allow Kurds to cut a strategic road connecting the IS stronghold of Mosul in Iraq to its territories in neighboring Syria. Major Raqib Shukri, currently deployed in Sinjar, says Kurdish factions hold the high ground and have successfully rebuffed more than 14 attacks in 21 days.

“Eighty percent of the city is under IS control, but these areas are under constant peshmerga fire,” he says.